OPEN LETTER TO THE CHESTERTOWN HDC FOR 206 CANNON STREET APPLICATION

Submitted by Thomas Kocubinski

February 2, 2024

Richard Moe, an attorney and renown preservationist, was president of the National Trust for historic Preservation for 17 years. He was dedicated to saving the Nation’s diverse Historic places and was known for creating more livable communities, particularly those within historic contexts. His view of Chestertown and its historic significance serves to elevate the mission of all who call out for the protection it is truly worthy of.

The following is written in response to the applicant’s December 27th letter to the HDC which used my December 2nd letter as a template. These responses provide clarifications, correction of misstatements, highlight the nonconformities and, more importantly, offer a creative solution for Chestertown’s Historic District in this matter. The solution would open a way to sensitively develop the last large land parcel within the National Landmark Historic District; a lot bounded by historic neighborhoods with important ties to the Town’s rich and diverse history.

For orderly presentation of the comments, SITE TOPICS are first presented followed by the BUILDING TOPICS.

SITE TOPICS

Immediate Neighborhoods

Part 1 – The Context

A view shared by numerous residents, including myself, is that it is vitally important to understand (1) and respect that Chestertown is designated as a National Landmark District. One of only five in Maryland to share such an honor, this unique distinction further places Chestertown within an elite group of National Landmark Districts that comprise only three percent of the approximately 90,000 historic districts in the Nation. Additionally,

Chestertown has the second largest collection of restored 18th century dwellings in Maryland, only behind Colonial Annapolis. It is therefore of compelling consequence that 206 Cannon Street, which falls within this distinguished landmark district, carries a high level of responsibility and requires a high bar of scrutiny when reviewing new construction for conformance.

(1) Applicants letter to HDC, December 27, 2023, page 1

From the Historic District Guidelines:

The thoughtful design of any new construction in Chestertown’s Historic District is of the utmost importance because it must harmonize with the character of the neighborhood and also be compatible with existing structures. A lack of attention to general design, to details, and to the context within which the building will be placed can have severe adverse impacts for the area. As a result, proposals for new construction receive serious scrutiny.(2)

Part 2 – The Proposed Design

The applicant’s recent letter to the HDC clearly represents that the context they and their architect embrace for inspiration and precedent is not the esteemed and recognized historic residential neighborhood but, instead, a collection of commercial structures including Stepne Station which is, ironically, not located within the Historic District. The letter repeatedly refers to the adjacent commercial buildings as ‘a neighborhood’ which it is not. Per planning standards, it is a commercial ‘district’ (only residential areas are defined as ‘neighborhoods’). Further, the 206 Cannon Street property is zoned for residential use while those properties relied upon for design inspiration are all zoned commercial. The dichotomy is clear. The consequential detrimental impacts to the adjacent intimate historic residential neighborhoods should be obvious with a house design inspired by large and bulky commercial buildings.

The lot in question should have been used as a buffer to protect the intimate historic neighborhoods with an appropriately scaled and crafted design. Choosing allegiance to the commercial district with a large-scale design over the predominately small-scale residences is disrespectful to the very essence of the historic district designation and its 18th and 19th century dwellings that drove the nomination. It was not the commercial district and its buildings that lifted the town to its esteemed level of notoriety and yet they are celebrated in bulk, massing, style, and materials in the proposed house design. The applicant’s logic in the context of a Landmark Historic District is seemingly illogical.

The letter further cites, ‘This large, currently underutilized lot provides more development opportunity than a smaller lot, and quite frankly warrants a larger design concept’. It references a ‘debate’ centered on how to ‘stitch together these districts of varying characteristics’. I have attended three meetings and no one, to my knowledge, was waging such a debate or talking about finding threads.

(2) Paragraph IV, New Construction and Additions, page 49

Part 3 – The Proposed Solution

In reference to the above statements regarding utilization of the lot, particularly justification for a larger design concept, I take this opportunity to propose a counter view.

This design concept pivots 180 degrees, offering a solution without detriment to the applicant’s intentions yet fulfilling the intent of the design guidelines and interests of citizens to protect the historic neighborhood and consequently their property investments.

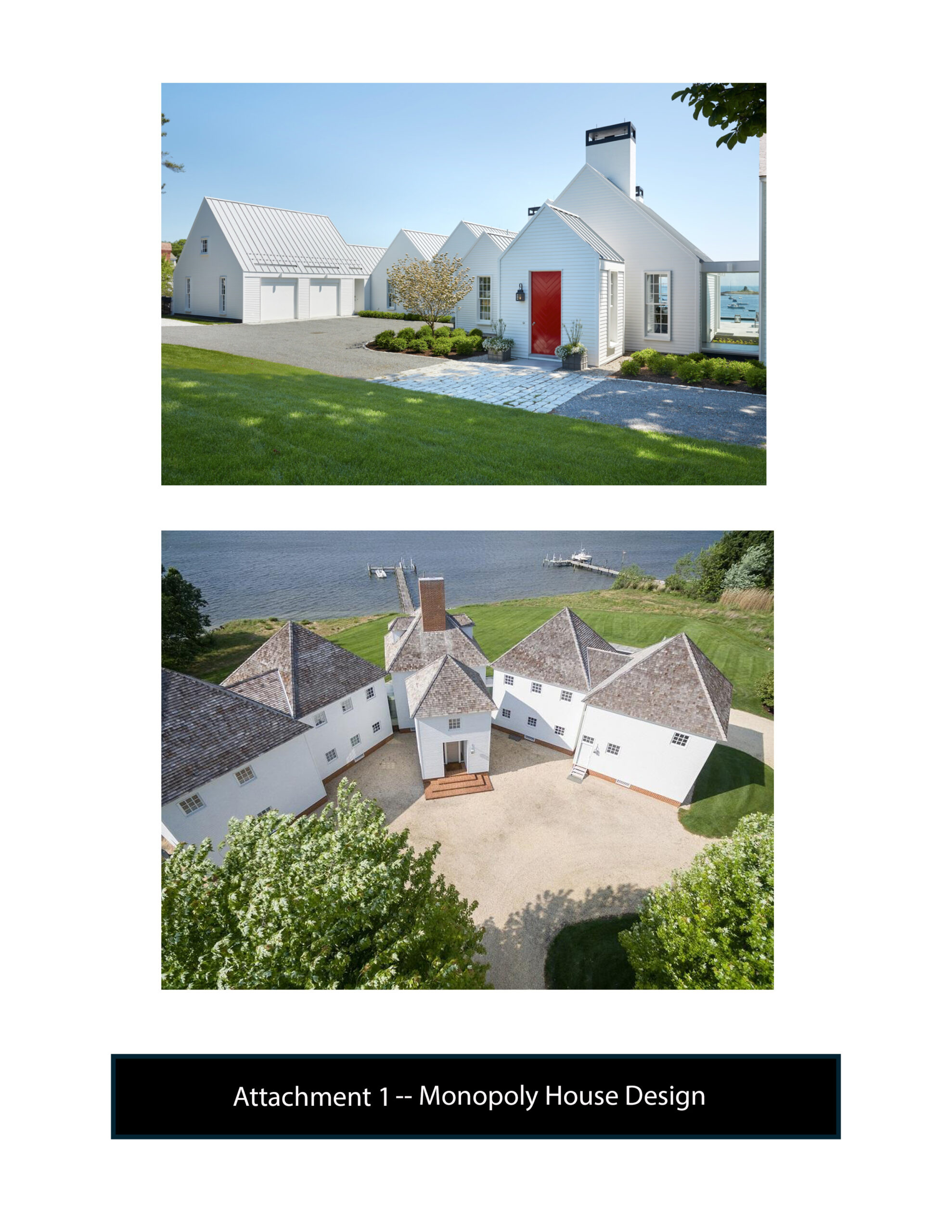

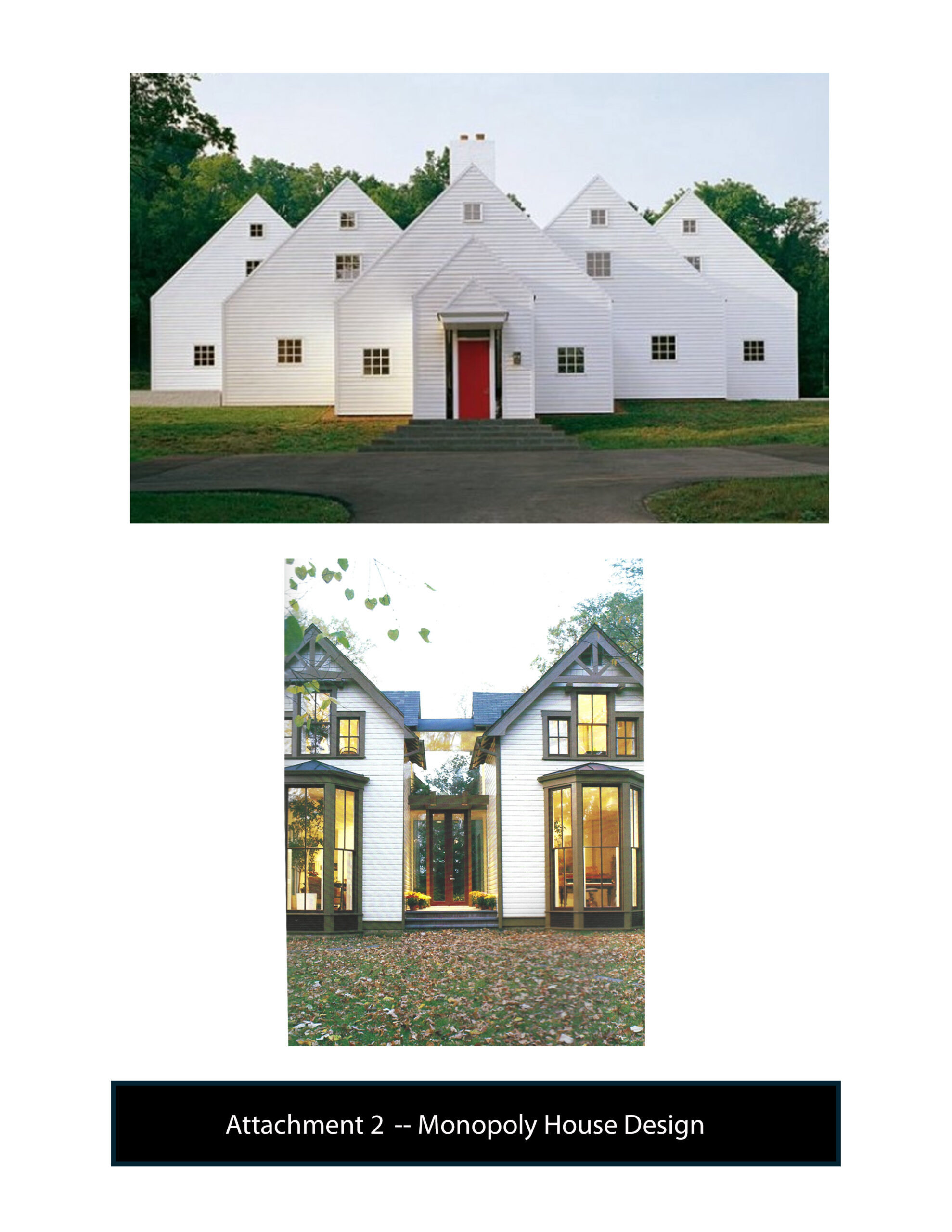

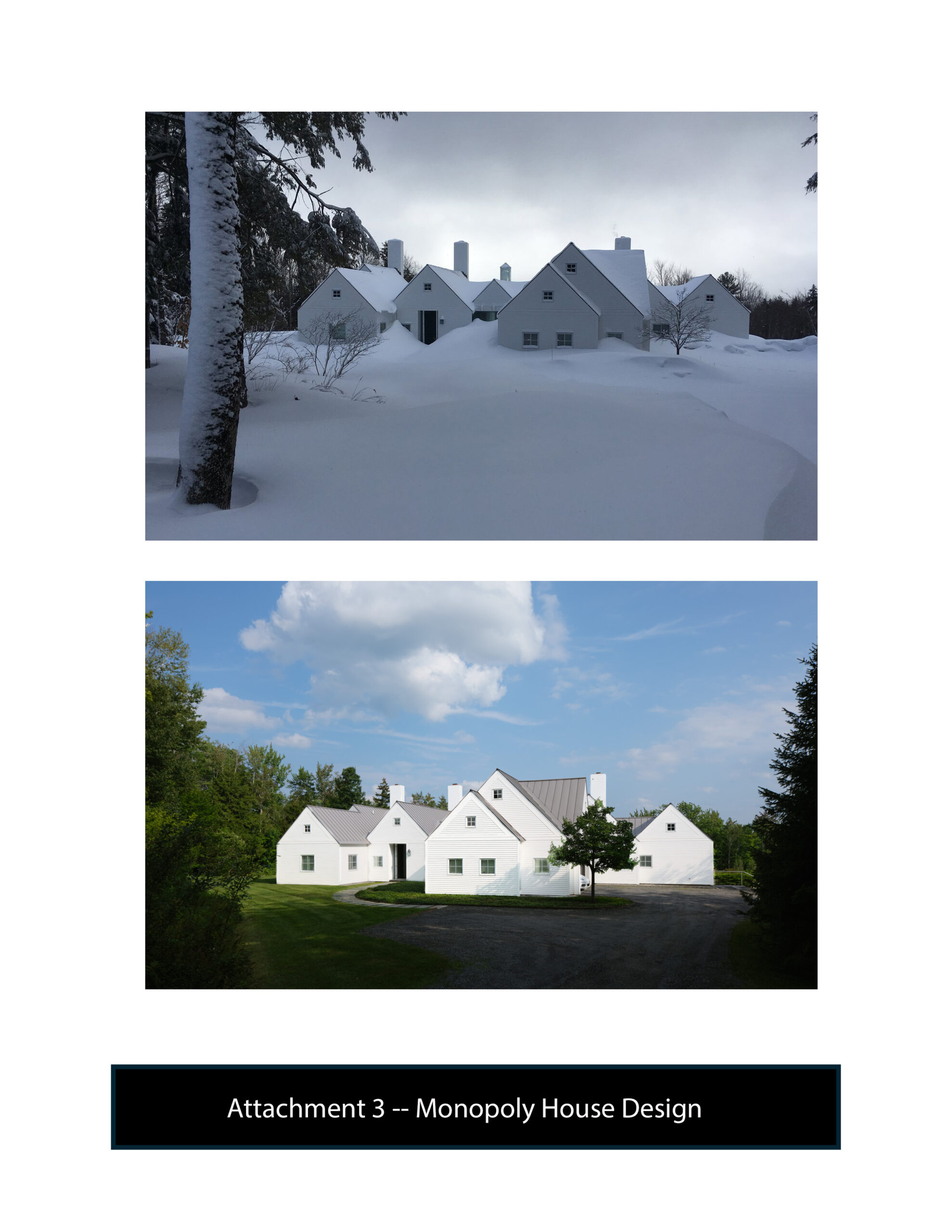

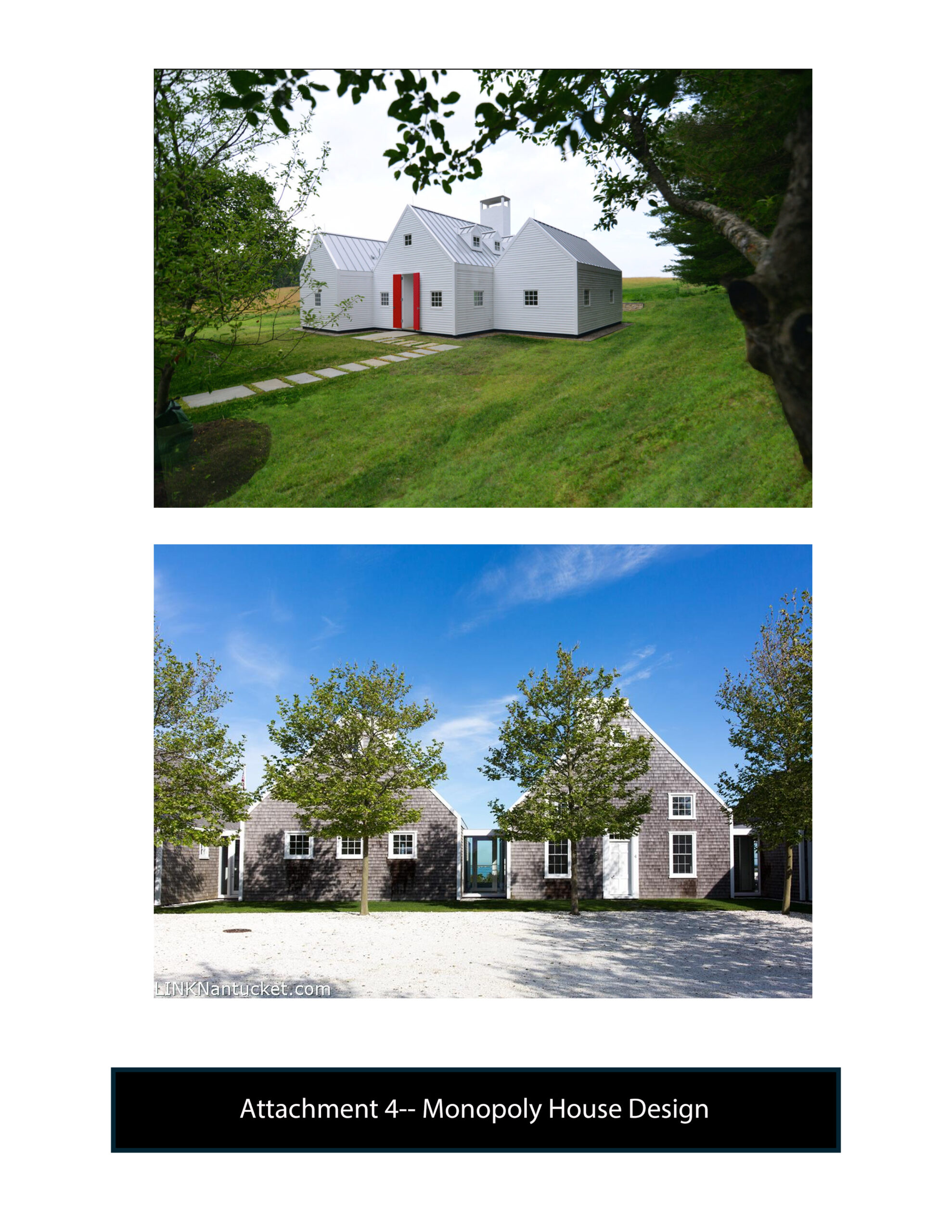

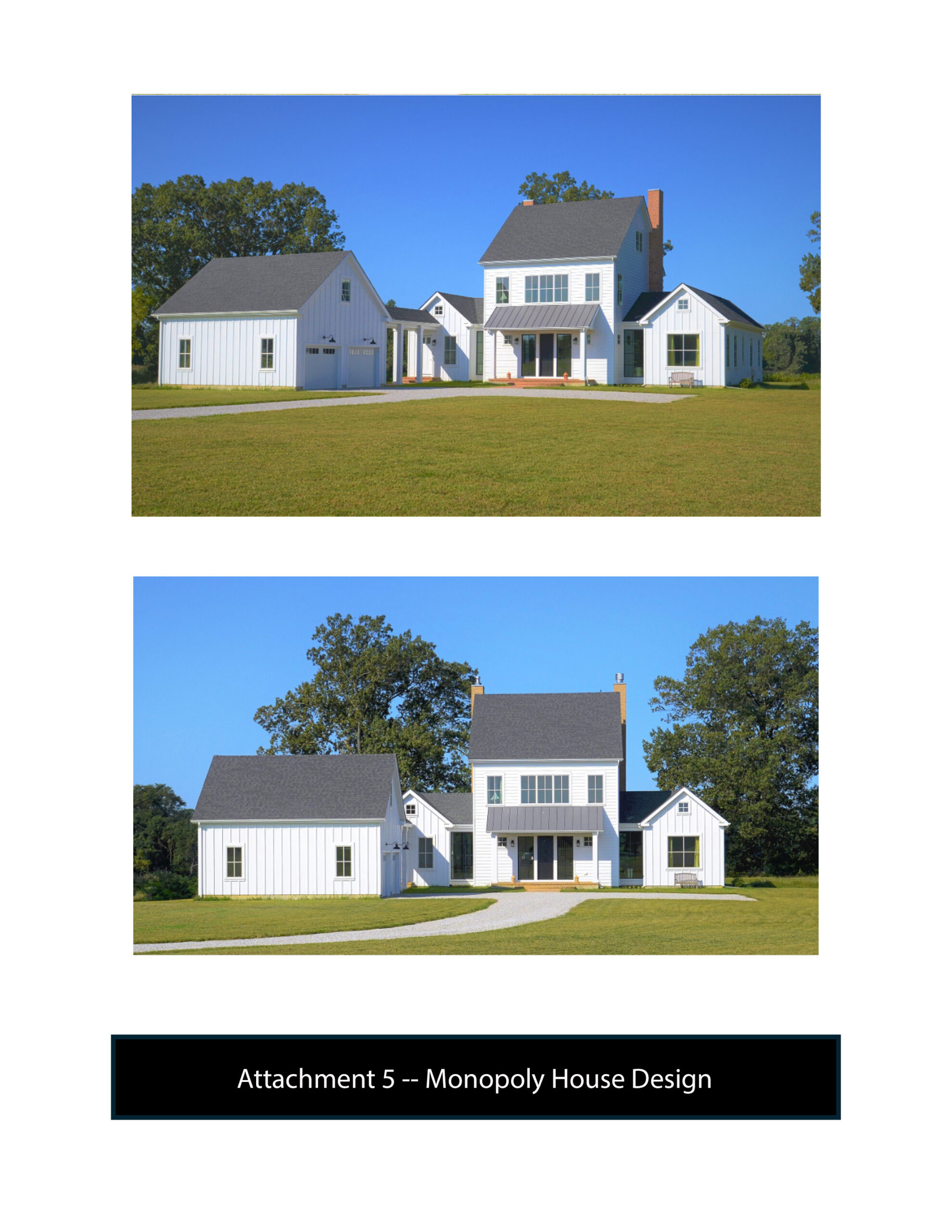

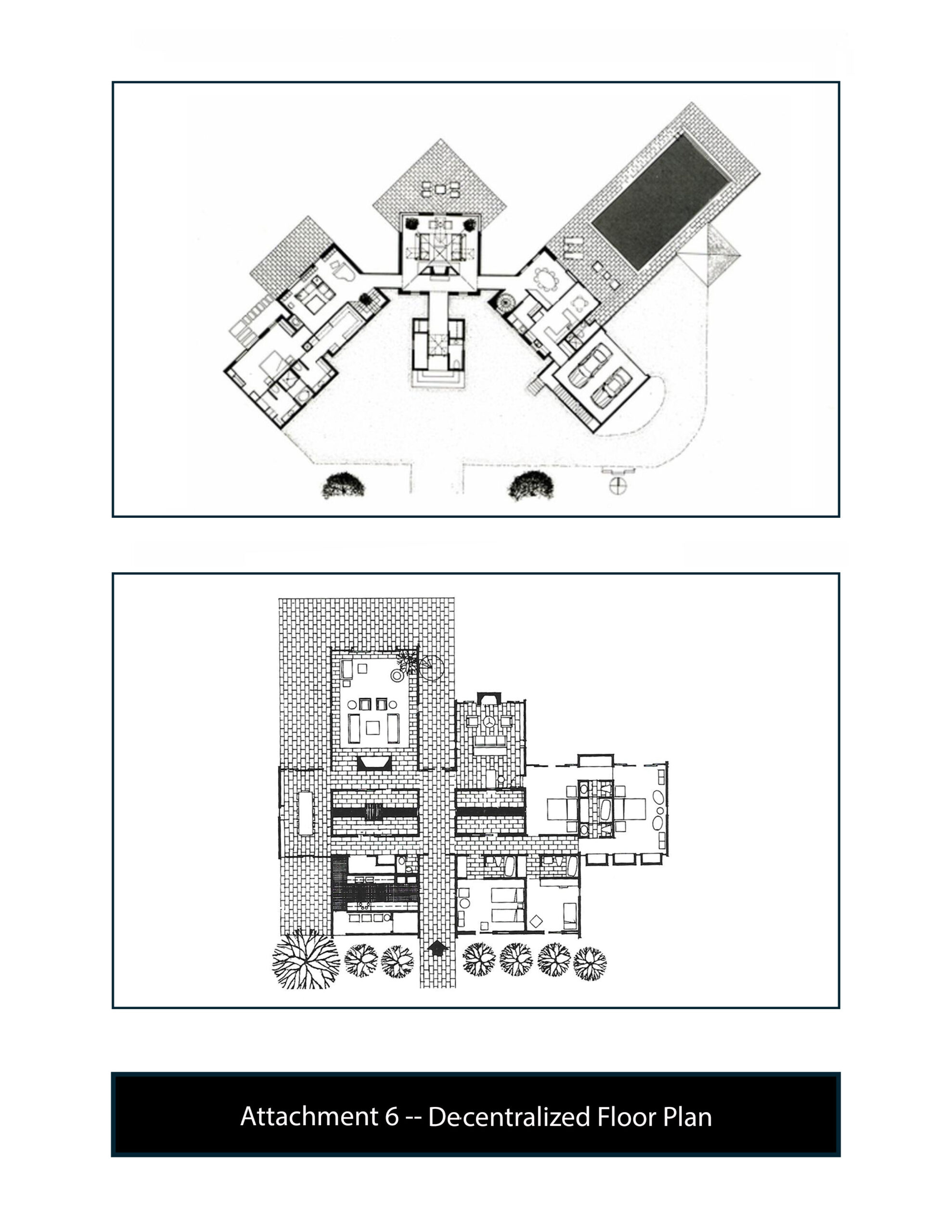

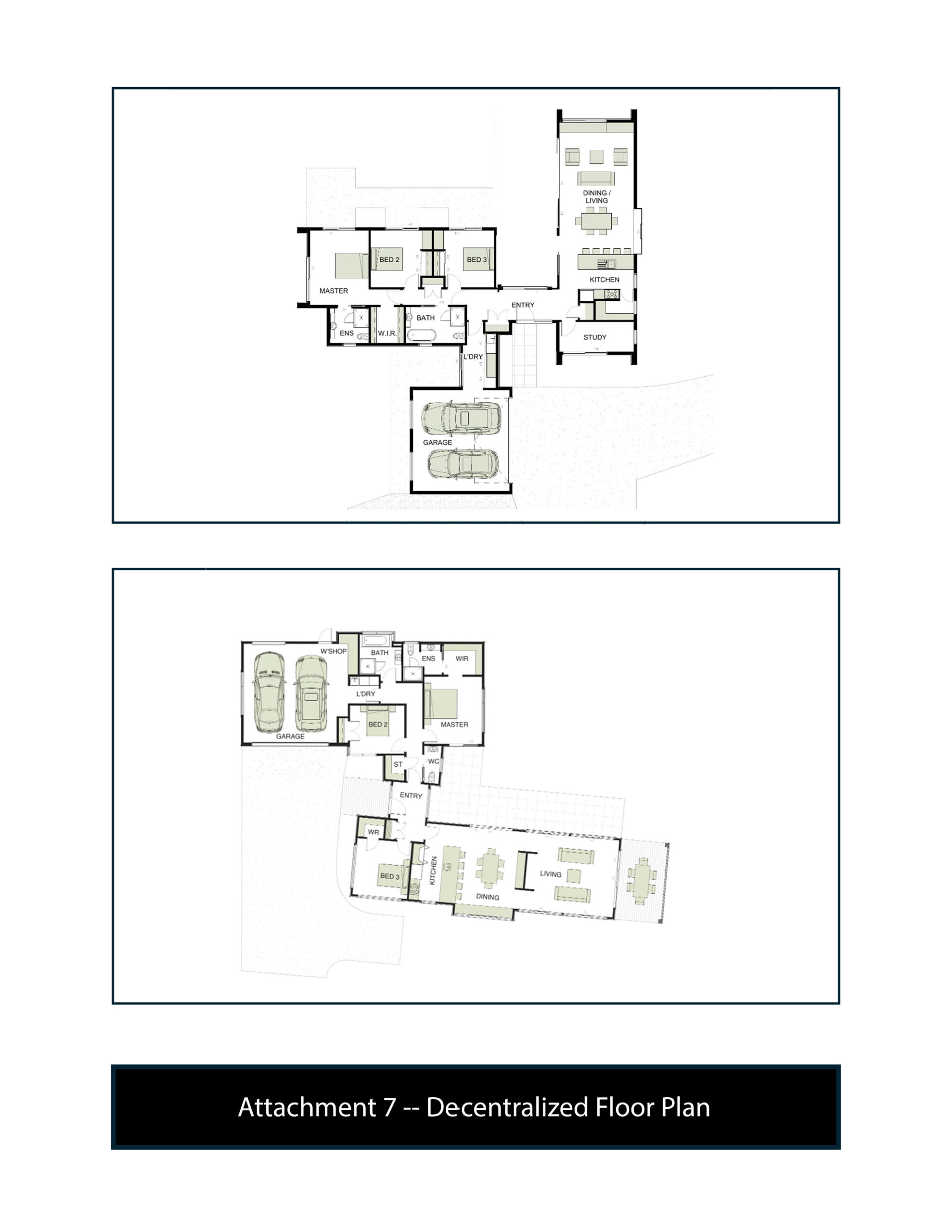

The following design alternative, a compromise, pays respect to the rhythm, scale, style, and integrity of the residential context. It is a concept called ‘decentralized design’, where major parts of the building are separated and expressed as individual design elements, also referred to as ‘monopoly houses’. These functional elements or house blocks are arranged in a fashion emulating a small-scale composition or neighborhood unto itself thus resulting in mass, scale, rhythm, and roof forms that would be sensitive and complimentary with the surrounding residential context. It works well with the large lot where it can ‘spread out’ and convey the correct character and ambience. Further, it would create an appropriate ‘southern gateway’ into town as viewed from Cross Street. With this simple concept, the client’s large building footprint is decentralized leading one to focus more on the individual building elements of the composition than on a singular building mass.

In contrast, the applicant’s proposed design can be regarded as a ‘centralized design’, with all building functions under a large contiguous roof form thus limiting the ability to scale the mass to become complimentary with the historic context. Predominately, the negative responses to the current design are based on restrictions inherent with a centralized design concept. It is a design trap with no way out, despite the architect’s attempts to do so. The Monopoly House Design concept can be scaled up and down in massing to transition between the residential and commercial scales more successfully than a centralized design concept. It can be skillfully crafted to achieve the required balance and visual tie to the surrounding neighborhood.

Successful examples of Monopoly House Designs are attached. Most are designs by nationally recognized architect Hugh Jacobsen, of Washington D.C. who died in 2020. Mr. Jacobsen designed simplistic but noteworthy residences on the Eastern Shore. Respecting the surrounding context was a key driver in his award winning and timeless designs. They have been successfully emulated by many architects to reduce mass, compose a uniquely scaled composition, and create a sense of place to enhance and elevate the surrounding area or context. It is a credible design concept that would work well at 206 Cannon Street.

In deliberating what is the highest and best design solution for 206 Cannon Street, the residential context mirrored in a decentralized design should be the driving force, not the commercial context mirrored in a centralized design.

Attachments 1- 5 are building elevation examples and 6-7 are decentralized floor plan examples. In tandem, the appropriateness can be understood and appreciated to fulfill the requirements embodied in applicable ordinances, guidelines, and goals of the Comprehensive Plan for Chestertown. It offers a win-win solution.

Zoning and Density

Understanding of the state and local historic land use legislation is important in order to address this critical topic. In 1963, Article 66B of the Annotated Code (Maryland Land Use Article) was amended to grant local governments the authority to protect and preserve their historic buildings. In 1964, Chestertown became one of the first towns in Maryland to adopt an historic preservation ordinance (Chapter 93, Historic Zoning) and in 2003, the HDC published the Historic District Guidelines with revisions in 2012. In 2015, the Chestertown Comprehensive Plan adopted the following goal.

“The need to protect and conserve Chestertown’s historic resources is a fundamental, underlying concept to managing the current and future growth of the Town. Chestertown’s character is shaped by its history, its architecture, and its pattern of growth over the centuries. Much attention and effort has been devoted to ensuring that current and future growth decisions reflect sensitivity to the need for compatible scale and character, particularly within and adjacent to the Historic District”. (3)

In short, it is apparent that the HDC possesses the authority to not only carefully scrutinize applications but also to require revisions or deny applications that are deemed not in the best interest of the Historic District.

The absence of a FAR in the zoning ordinance Bulk Standards for the R5 Zone appears to have been insightful. It recognizes the organic, rich character, growth and diverse fabric of the adjacent historic residential neighborhoods and serves to promote its continual evolution in the spirit of what has come before. It can be considered as aiming the community toward something more than the sum of its parts. FAR is not favored if the planning objectives include,

(3 ) Chestertown Comprehensive Plan, page 75

- Conserving and enhancing the neighborhood character, particularly in a historic district

- Creating a fine-grained built environment with diversity of ownership

- Consideration of factors impacting the environment such as new buildings, greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption or repercussions on local ecosystems including storm water runoff

The R5 zoning correctly applies to a historic district in that it recognizes and promotes evolution of the district and its neighborhoods. The absence of a FAR dovetails favorably with the planning concept of fine-grained urbanism, described as follows.

Fine-grained urbanism promotes small blocks in close proximity, each with many buildings with narrow frontages and minimal setbacks. Also, as there are more intersections, traffic is slower and safer. This fine-grained approach offers many opportunities for discovery and exploration. Like high count Egyptian cotton; fine grain urbanism feels luxurious and makes people want to linger in or around it. Fine- grained urbanism is not imposed on a community. Rather, it evolves over time in a piecemeal way, responding to what came before it, and adapting to what comes next. This evolutionary process creates places that are not frozen in the era when they were built. Instead, they are dynamic and reflective of a neighborhood’s changing needs. (4)

With absence of a FAR, the default design criteria for evaluation of the applicant’s proposed project are found in the Historic Zoning Ordinance, the Historic District Guidelines and the Comprehensive Plan. All of these documents include goals, requirements, and guidelines which establish the parameters for a focused evaluation consistent with the principals of fine-grained urbanism. The following excerpts or references are noted as being applicable to this application.

- Chapter 93: Historic Area Zoning: 93-10, Factors Considered When Reviewing Plans

- Historic District Design Guidelines: Section IV, New Construction and Additions

- Town of Chestertown Comprehensive Plan: Land Use Element, Design Principles for Chestertown and Historic Resources Element

All of these documents share a consistent notion that the Chestertown Historic District is unique and special requiring sensitivity to the need for compatible scale and character and affixing focus on the need for complimentary massing, scale, rhythm, size, height, setbacks, roof forms, fenestrations and materials for new construction including infills.

The review for fitness of the proposed design is held to a much higher standard due to the absence of a FAR. Compatibility with the National Landmark Historic District and the adjacent historic neighborhoods must be impeccably achieved. If reviewed in the context of the foregoing, the proposed house design does not meet the criteria for compatibility as the following sections will convey.

(4) Yuri Artibise, Fine-Grained Urbanism: Opportunities for Discovery, 2010

Site Plan Layout

The benefit of a single-family house on the lot with preservation of open space should not be overlooked. However, this does not assuage the applicant’s obligations to conform with applicable ordinances and other protections afforded to the National Landmark Historic District, its adjacent historic neighborhoods and the voices of many citizens interested in protecting property investments and quality of life. Exception is taken to the reference of ‘two ailing streetscapes’ and the stated ‘cure’ being the applicant’s suggestion to sell off lots for infill development. Surely, after 300+ years of perpetual motion, Chestertown should be able to find a solution if there is truly an ‘ailment’. Exception is further taken to elevating the importance of the commercial bulks over the intimate historic dwellings that fall within the architect’s undisclosed ‘radius’ of importance. The ‘opponents’ (residents) are justifiably correct in their concerns, and sweeping aside their views with the vague radius reference is not productive in overcoming the current impasse. An appropriate balance is needed with the residential neighborhood and relating the design to the commercial bulks will not achieve the required balance. However, if a design solution can incorporate a means of transitioning the scale, all the better, but it should not be the primary driver — protection and compatibility of the historic district is the priority. As previously noted under the ‘Immediate Neighborhood’ section, the Monopoly House Design concept affords the pathway to resolution of the dilemma, and it is within the purview of the HDC to require such a compatible redesign.

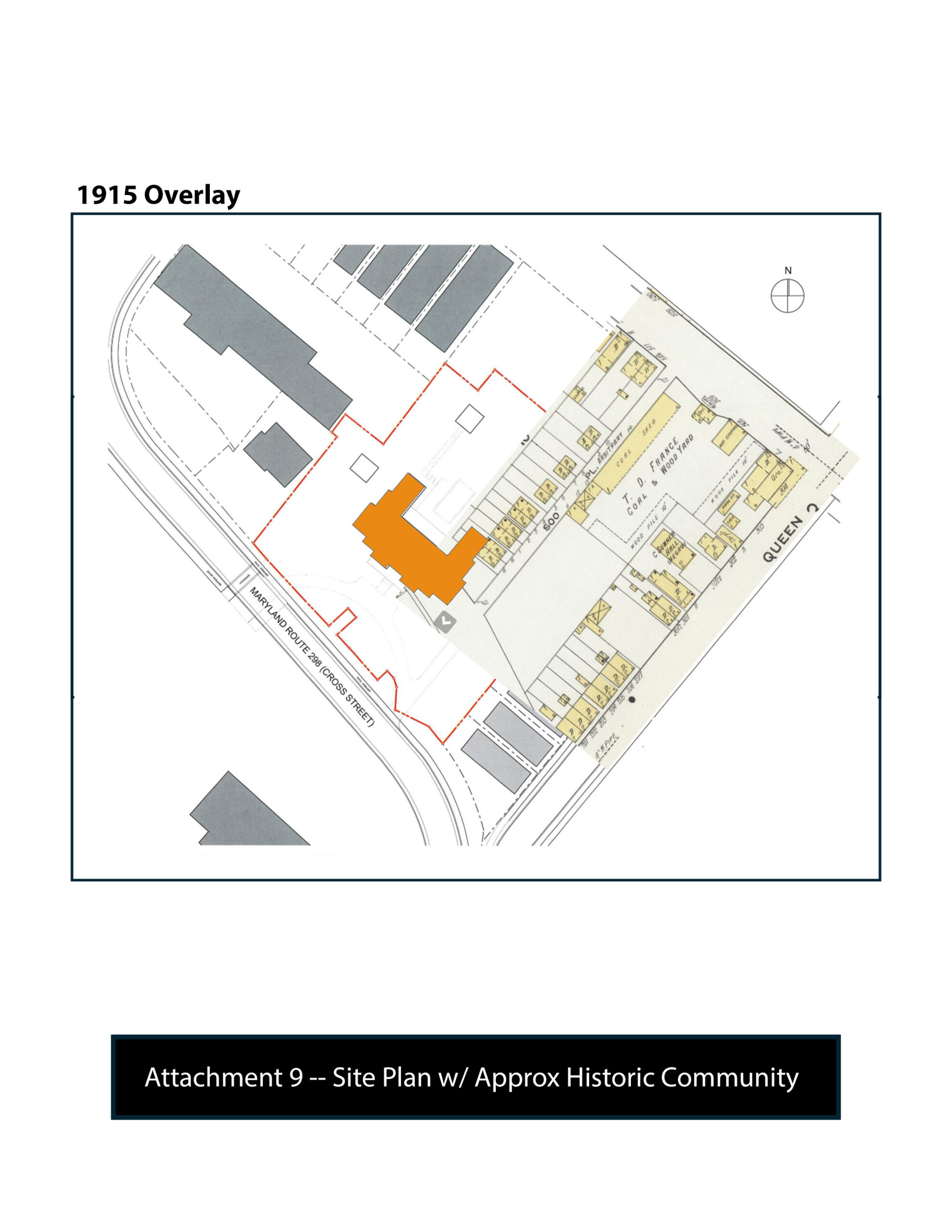

Related to the Site Plan is the recent discovery of apparent significant African American history on this land parcel. Referencing the Sanborn Fire Insurance maps of 1891, 1903 and 1915, all indicate the formation and buildout of a small community on the parcel westerly of the former France Coal, Lumber, and Hay. There was a dedicated road on which the houses were located, referred to as both France Lane and Soo Place. Further, the map clearly shows the existence of 6 duplex dwellings thus accommodating perhaps 12 families. With the already chronicled African American history on both South Queen and Cannon Streets, the small enclave was assuredly part of this greater community. This new information is important to Chestertown’s past and timely to the state of Maryland’s current mission to document diverse history and preserve diverse historic sites. The African American Historic Preservation Program (AAHPP) was launched by Governor Moore and the Maryland Historic Trust (MHT) has received a $50,000 grant from the National Park Service through the Dept of the Interior to document Chestertown’s diverse history. These developments should trigger reconsideration of a recent decision to demolish the existing outbuilding on the property locally referred to as the ‘Tin Roof’ having a history of African American entrepreneurship. To what extent these programs impact the HDC’s deliberations remains unknown, but records show there may in fact be valuable history associated with this parcel that will need to be considered in the project approval process.

Refer to Attachment 8 for the historic maps and Attachment 9 for the approximate location of the dwellings and roadway superimposed on the applicant’s site plan.

Semi-Circular Drive

The task before the HDC is to determine the appropriateness and precedent of the proposed 145-foot-long circular drive in the context of the historic district. Although the MDOT has given approvals, the HDC should be focused on overseeing thoughtful design that harmonizes and is compatible with the character of the district. The highway department did not stipulate the circular drive, the applicant did. MDOT is charged with the technical review of the applicant’s design. Why didn’t the applicant propose a single drive and curb cut at Cross Street leading to a parking area with a garage? This arrangement aligns with the historic standard and precedent throughout the town. Wouldn’t one curb cut be safer than two on a curve with two-way traffic and fluctuating volume? What about the impacts of future growth? Additionally, the circular drive is an unnecessary and unprecedented affectation in the context of the immediate historic district. Even adjacent Wilmer Park, with its 46 parking spaces, and at times high traffic volume, relies on a single drive and curb cut at Cross Street.

With the Monopoly House Design concept, the garage is typically a separate building with connection to the dwelling block via a covered or enclosed link. By positioning the garage in alignment with the applicant’s proposed driveway from South Queen Street, the circular drive can be omitted thus maintaining the historic character of the neighborhood and eliminating safety concerns at Cross Street. MDOT would not be involved with a driveway from a town road.

Outbuildings

Having been in attendance at three HDC meetings on this matter, I do not recall specific outbuilding review comments. The only previous comments on record appear to be mine submitted via my December letter. Outbuildings are important contributing elements of an historic district. Reflecting this view, Paragraph IV.4 Accessory Buildings was included in the Design Guidelines. The proposed outbuildings do not comply as they fail to meet the compatibility requirements with respect to the principal building and are surely not ‘sited as unobtrusively as possible’. Further, the tool shed structure can be readily seen from the public right-of-way, furthering the non-compliance. It is requested that the HDC conduct a review of the proposed two outbuildings commensurate with the provisions of the Guidelines and consider recommending both redesign and relocation.

Infill Lot Concept

Infilling the existing ‘holes’ to complete the neighborhood is a credible approach to restore and bolster the neighborhood and provide a conjoined sense of place along South Queen and Cannon Streets, thus elevating the historic district experience and goals of the Town. The concerns with an infill proposal is that it is merely a concept without commitments, timelines or guarantees. However, the Monopoly House Design would sensitively complement the infill concept by providing a house design with aligned scale, bulk and massing consistent with future infill dwellings. This design concept brings the neighborhood character onto the lot, thus providing design consistency. Further, it keeps the commercial scale and bulk where it belongs, in the commercial zone.

Access to Parking in Rear of Properties

An optional benefit of this accommodation is that the proposed access road from Cannon Street can be extended to service the applicant’s proposed project site thus providing a second means of access for personal and emergency uses.

BUILDING TOPICS

Rhythm and Scale

The terms rhythm and scale are used extensively in the Design Guidelines, Historic Zoning Ordinance and Comprehensive Plan, thereby emphasizing their importance in the context of planning and design criteria for Chestertown. Further, these are defined terms in the Design Guidelines allowing the design to be duly evaluated. On page 51, IV.3.2 Rhythm, cites ‘New construction designs should analyze existing patterns or rhythms and incorporate them into the project’. On page 52, IV.3.4 Scale, cites ‘For new construction these relationships should be compatible within the building and with other buildings in a visually related field.’ And additionally, ‘Chestertown is above all a town for pedestrians and new buildings should maintain that human scale’.

For clarification, the Guidelines do not state ‘commercial scale’. The 206 Cannon lot is located within the boundaries of an R5 residential zone and the Landmark Historic District. Despite which way the house faces, it does not change the fact that the house must conform to the historic design standards.

Regarding the importance of rhythm and scale on Cannon Street the Comprehensive Plan provides the following, ‘Future development should be of a scale and type that fits the character of adjoining and nearby streets.

Bulk Size Square Footage

The genesis of the issue involves the architect failing to clearly answer a question from a member of the community at a much earlier meeting regarding the gross square foot area of the proposed house. I was in attendance when this caught my attention. At the December HDC meeting I asked for clarification, but the response was again unclear. The applicant’s current letter provides a calculation, but it is still not the figure requested. What I requested was the Gross Foot Area (GFA) of the entire house – the area for both floors

measured from the outside of exterior walls for all spaces under the roofs (omitting the attic and basement). This is a common measurement, used routinely for cost budgeting, building permit forms, etc. It is easily and routinely calculated. The GFA is key in

establishing the bulk size of the house on the site and in the visual field. It is necessary in order to conduct a fair analysis and for comparison with the size of existing adjacent

residences. However, this is not what was provided in the applicant’s current letter. What is provided is the Gross Habitable Floor Area (GHFA) which measures the area under roofs but only within the interior and exterior walls, in other words, omitting the wall thicknesses. It further omits the garage and other non-habitable spaces. This number does not represent the overall size of the building mass and, therefore, serves no use in the visual analysis of the house and for conducting building size comparisons. I previously calculated the GFA at approximately 8,000 square feet and regard this as reasonably accurate.

Therefore, the proposed house exceeds the average size house located on South Queen Street by a factor of 4.5 to 1. The architect should provide the actual GFA for accurate building bulk and visual field comparisons.

Length of Facade: Front

The thrust of the architect’s argument is that the two 15-foot flanking wings at each end of the main house block are set back and will not be obvious in a frontal or skewed view of the house front, thus rendering the house to be visually 70 feet wide rather than the 100 feet that it is. However, the wings are only offset from the front elevation by two step backs, one at 4 feet and the other at 4 feet 8 inches for a total of 8 foot 8 inches, which will have little appreciable visual impact. The 100-foot front elevation expanse is, therefore, a conjoined mass and will be perceived as same. On its own, the 70-foot-wide main house block

exceeds the average house width on South Queen Street by a ratio of about 3 to 1. Using the 100-foot expanse, the ratio increases to 4 to 1. The house is demonstrably out of scale and incompatible with the adjacent neighborhoods.

Length of Facade: Side

The ‘Roof Height and Pattern’ section of the applicant’s letter transmits that the 34-foot ridge height is taller than those on Cannon and Queen Streets. To address the problem, the architect states that subsequent infill construction in combination with landscaping will effectively block views of the side elevations. However, the infill roof heights will be lower due to smaller building footprints. Trees take many years to attain the height necessary for proper screening and a tree can be gone in an instant due to climate catastrophe.

Additionally, the infill is merely a concept as explained previously with no timing, no scope and no warranty of it ever being implemented. I recently walked easterly toward Stepne Station on the rail trail to experience the vista of the house site from that direction. There isn’t any building now, nor will there be in the future, on the westerly side to block the frontal and side views of the house. Landscaping as a tactic is dubious to effectively hide the 34-foot-high ridge, twin gables and shed dormers. Therefore, it is not possible to effectively screen the large house from view. The Monopoly House Design concept would result in shorter exterior wall lengths, lower roof lines and would not be objectionable if not completely screened.

Roof height and Pattern

My December letter addressed numerous concerns with the roof design. The current resubmission does not acknowledge the input nor the provisions of Paragraph IV.3.37 Roof Shapes and Materials, which cites, ‘Roof profiles are an important element in defining the architectural character of an area. The shape and orientation of a new building’s roof should be visually compatible with the buildings to which it is visually related. Shed dormers are likely to be appropriate only on secondary elevations’.

Despite the proposed roof exceeding the height of the adjacent residences, the architect justifies the decision to do so by applying the commercial building ‘neighborhood’ argument, which was previously addressed in this letter as being inaccurate. It is ironic that more importance is placed on awkwardly massed bulk commercial buildings than the elegantly designed and period style buildings within the adjacent historic neighborhoods. Because the house openly fronts both Cross and Queen Streets, it has two primary elevations, both of which have large shed dormer roofs. These are not permitted per the Guidelines. The Monopoly House Design concept would afford the opportunity to compose and arrange the roof heights and patterns in a compatible composition with the residential context.

Windows ar Stair Enclosure

The Guidelines, in Paragraph IV.3.8 Windows and Doors cite, ‘The proportion, size, detailing, and number of windows and doors in new construction should relate to those of existing adjacent buildings’, and further, ‘The fenestration pattern on new construction should mimic that of adjacent structures’. The proposed window execution is not in conformance with the Guidelines. Rather than turning to the immediate adjacent buildings the architect has chosen to scout the commercial district for examples of commercial

installations to justify a modern composition of windows in the house design. This was done despite the very clear prescriptions in the Guidelines that thoughtfully address window selections, sizes, and patterns. These standards should not be disregarded.

Material Selections

Having attended meetings where brick selections were presented and discussed, I find the HDC’s request for consideration of a red brick to complement the historic context is not arbitrary nor without foundation. The brick colors proposed by the architect are not found within the immediate residential neighborhoods which is relevant because it furthers the nonconformity and incompatibility of the current house design.

In summary, the preservation and protection of the esteemed Chestertown Historic District must be of paramount importance to all parties involved in the project approval process, regardless of which side of the fence you find yourself. Commitment to preservation and protection of our precious resource with cooperation to achieve this goal should be the focal point bringing sensible commonality to this process. If all are so invested, the highest and best resolution will emerge and prevail. A sound and reasonable design compromise has been presented and my hope is that it will be seriously considered. It serves no purpose to run against the grain of 300 years of evolution still in the making.

The cherished sense of place enjoyed by residents and visitors alike can be compromised with one unwise decision creating an unfavorable precedent, possibly leading to a slippery slope never considered.

In my view, the HDC is the most important participant in the approval process. Fortunately for the HDC, their focus is narrowly defined by well framed statutory dictums and guidance which not only confers significant responsibility but also provides significant powers. I ask that they be assiduously applied in order to preserve and protect a unique historic resource, our National Landmark District.

As Richard Moe said many years ago, Chestertown had the good sense to preserve its historic district and that good sense is not only needed today but for all time. In the spirit of the many who have come before us to deliver our beloved Historic District, I ask for your good sense.

Respectfully submitted,

Thomas Kocubinski, AIA Preservation Architect

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.