Last Supper images were infrequent in early Christian art. A very few from the 2nd to the 4th centuries can be found in the Christian catacombs around the city of Rome, and 6th century mosaics at Ravenna. In the Gothic era (mid-12th Century) the Roman Catholic Church accorded Mary the status of Mother of God and Queen of Heaven, and seated her next to Christ in the Last Judgement. Churches devoted to Mary were built and named Notre Dame. Artists were called upon to depict Mary in a more human and realistic manner in stories of her life and the life of Christ. As a result, the Last Supper became one of the most popular new subjects.

At Notre Dame de Chartres, 167 stained glass windows were installed from the years 1190 until 1220. The “Last Supper” (1205-1215) is part of the Passion window that contains fourteen scenes of the Passion. Christ raises his right hand in the traditional gesture of blessing, while his left hand reaches across the table as if to point at Judas. Judas, without a halo, is placed alone at the front of the table. Wearing green and yellow robes, he reaches toward Christ. The youngest disciple John, placed directly in front of Christ, rests his head on his hand on the table. It will become a tradition for John to be shown sleeping. All twelve of the disciples are not included in the small space. All have either gold or red halos, except Judas. Christ’s halo is a trinity halo with the white cross against the red disc.

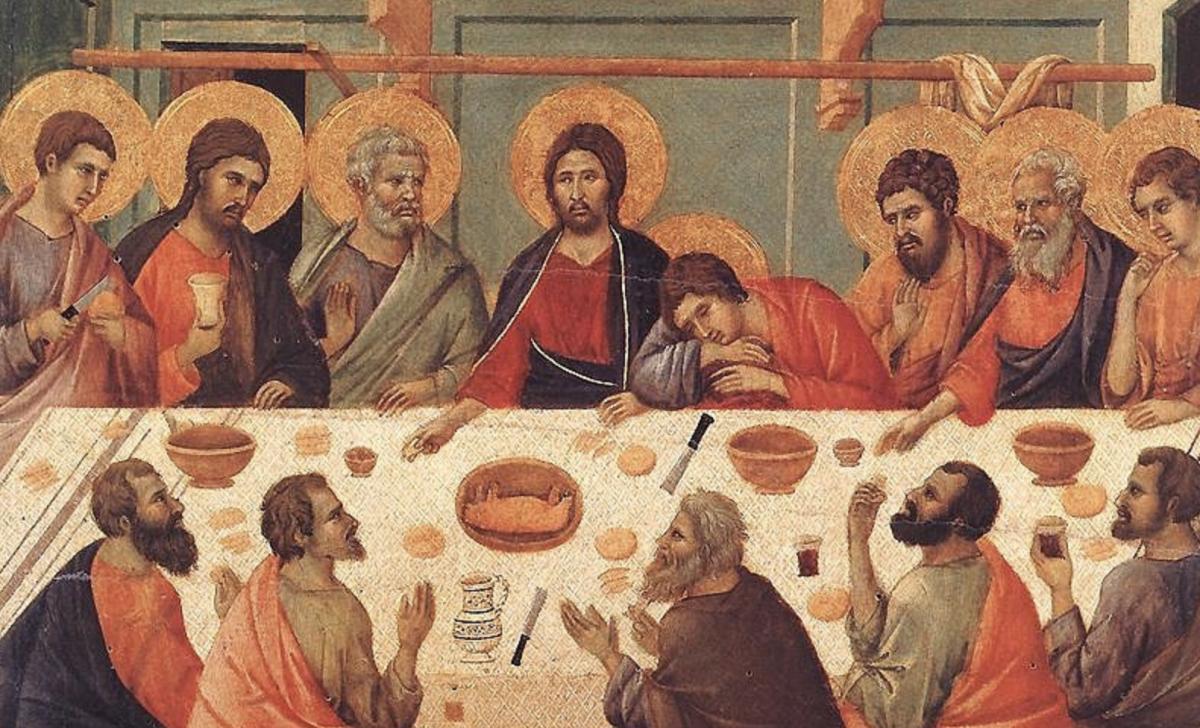

French churches were constructed with stone walls to protect the congregation from the cold northern weather. Painting on cold stone walls was not feasible. As a result of the warmer climate of Italy, church interiors were warmer, and it was possible to create large frescoes on plaster walls and large wooden painted altarpieces. Duccio’s “Last Supper” (1308-1311) is from a tempera on wood double-sided altarpiece known as the “Maesta” (7’h x 13’w). The front was dedicated to the Virgin in Majesty (Maesta) and the back to Christ, beginning with scenes of the Entry into Jerusalem and through Christ in Limbo. This was one of the first times an artist was tasked with depicting so many different scenes dedicated to the life of Christ and Mary.

Duccio was one of the first great early Italian Renaissance painters. Without teachers, he taught himself how to create three-dimensional space and depict 13 clothed figures of different ages. Christ is placed at the center of a long table that holds several bowls, rolls, and a pascal lamb on a platter at the center. Nine figures, with Christ at the center, are seated at the rear of the table. Duccio identifies Christ by the dark blue cloak edged in gold. At Christ’s left, young John is asleep. Three disciples are placed to either side of them. As a result of his lack of knowledge of anatomy and skill in creating facial expression, all of the disciples have essentially the same face. Their ages can be discerned: the young being clean shaven, the middle aged with brown beards and hair, and the old have white beards and hair. It will become a tradition for John to be on Christ’s left and Peter to be on the right. Peter is holding a knife, possibly a reminder that he will cut off the ear of one of those who arrest Christ. The remaining five disciples are seated on a bench at the opposite side of the table. Judas is at the right, the only disciple with black hair and beard. Christ holds a piece of bread in his right hand; at the lower edge of the table is the pitcher of wine.

Duccio was faced with other challenges in creating this scene. He is not able to depict the table in accurate perspective; it decidedly slants from back to front, in danger of dumping everything on the table into laps of the five on the bench. These figures in the foreground are seated in uncomfortable side facing positions so their faces can be seen. Duccio was unable to paint them with halos because he did not have the skill to create perspective. Duccio did manage to paint the Renaissance style wood paneled ceiling supported by carved beams that slant diagonally to create perspective. The two doors into the room are far too small to accommodate any of the figures, and if they should try to stand up, their heads would break through the ceiling. Nevertheless, Duccio’s painting is extremely advanced for the era, and the response by the viewers was nothing short of amazement.

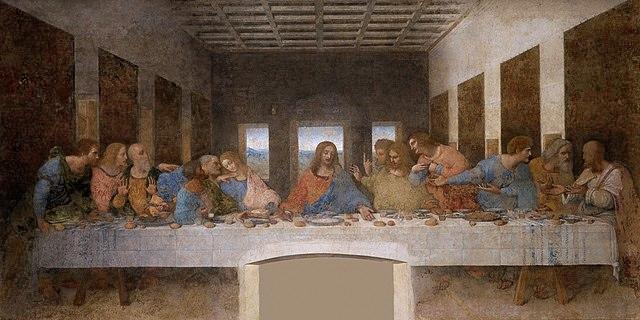

Da Vinci’s “Last Supper” (1495-98) (15’ h x 28.8’ w) is one of the world’s best-known works of art. Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan commissioned the painting on the refectory (dining room) wall in the Dominican monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. It has become the quintessential image of the Last Supper. The twelve disciples sit comfortably at a large horizontal table. The well laden table is covered by a white table cloth with a lace pattern on the edges, wine glasses, bowls, rolls, fish, fruit, and wine. Christ has just said, “Verily I say to you, one of you will betray me” (John 13:21), and each disciple, depicted with respect to their age and different facial expressions, respond to the pronouncement.

By placing all the disciples at the same side of the table, da Vinci changed the dynamic of the event. To Christ’s right are John, Peter and Judas. John leans back toward the gray-bearded Peter, and John’s pose creates a wide divide between himself and Christ. Peter leans forward toward Christ, while Judas leans backward at the same angle as John. Of all the disciples, Judas is the only one in shadow. None of the sunlight from the three outside windows reaches Judas. He is in darkness, holding a bag that is presumed to contain the thirty pieces of silver he received to betray Christ. He reaches across the table toward Christ, while Christ has extended both hands, palms up, to deliver His message.

Da Vinci was a painter, sculptor, architect, inventor, and mathematician, to name a few. He devised this composition based on the numbers three, symbol of the trinity, and four, symbol of the four gospels. Christ’s pose is a triangle, the top of his head centered in the composition, taller than the others, and singly in front of a window. None of the figures has a halo. Leonardo did place a stone arch over the window behind Christ to suggest a halo. Three windows light the room. The side walls of the room contain four panels. The disciples are arranged in four groups of three figures each. The only disciples who lean away from Christ are John and Judas, whose poses create an upside-down triangle. Each of the four groups of disciples is posed in a modified triangle. One exception to the geometry of the space is the slightly arched break at the center of the table. The refectory kitchen was behind this wall, and food was delivered through a door at the opposite end of the room. Objections to cold food by the monks eventually resulted in a door being cut in the wall in 1652, allowing direct delivery. Refectories became popular places for Last Supper paintings.\

Da Vinci’s painting has suffered many disasters. To begin with, the painting is on an exterior wall. He wanted the colors to be brilliant like oil paints, and he experimented with pigments. A white lead undercoat gave the paint the glow that he desired. Unfortunately, the paint began to flake within a few days. The “Last Supper” is often referred to as a fresco, but it is not. Da Vinci used oil paint and tempera on dry plaster. By 1518, flaking and fading was noticeable. The first restoration began in 1726, and more would follow. In 1796, French troops used the refectory as a stable and armory, throwing stones at the painting and climbing up to scratch the eyes out of the disciples. The room was flooded. It was used as a prison. On August 15, 1943, Allied bombs struck the refectory. The monks had sandbagged the wall; as a result, it was the only thing left standing. A modern restoration took 21 years, and the “Last Supper” was reopened on May 28, 1999. The painting could not be moved because of its size and fragile state. Despite its long history of damage and restoration, da Vinci’s “Last Supper” remains today in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie. It is regarded as a great masterpiece by a great master.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.