Vicente Jose de Oliveira Muniz, born in San Paulo, Brazil in 1961, struggled in school because he was dyslexic and turned to drawing to accomplish his school assignments. When he was 14, his math teacher suggested he enter an art contest, and he won a partial scholarship to an art studio. His interest in art grew, and at age 18 he enrolled in a publicity and advertising course in Sao Paulo. He took a job in an advertising agency where he redesigned bulletin boards to make them easier to read. That same year he was shot in the leg while trying to break up a fight. The shooter offered him money not to press charges. He used the money to travel to Chicago where he stayed with his aunt. He studied English, but learned Polish, Italian, Spanish and Korean from his fellow students. A visit New York in 1984 included a trip to the Museum of Modern Art, where he was inspired by the photographs of Cindy Sherman and the balloon sculpture of Jeff Koons.

After the visit to New York, he moved there that same year. He lived in the east village and eventually opened a studio and started to make sculptures. His first exhibition was in 1988. After spending a year and a half in Paris, he returned to New York City in 1992 with a new concept for his art. He began to use historic art images with new and unusual media to bring them back to life in a new light.

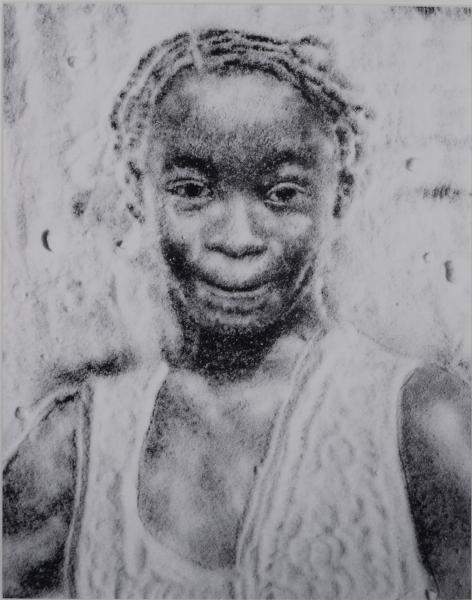

Muniz’s series “Sugar Children” (1996) (14’’ x 11’’) (gelatin silver print) brought him to the attention of the art world. “Valentina, The Fastest” (1996) is a portrait of one of six children he met and photographed during a visit to the Caribbean. The children’s parents and grandparents had worked on sugar plantations in Saint Kitts. Valentina has a big smile and looks like a happy child. Muniz created the portrait by placing white sugar on black paper until he achieved a photographic likeness, and then he photographed the work. He then wiped the paper clean and repeated the process for the next image. Thus, the original work of art was temporary and destroyed.

The titles Muniz assigns to the portraits of the other five children make the viewer smile: “Jacynthe, Loves Orange Juice,” “Big James, Sweats Buckets,” “Lil’Calist, Can’t Swim,” “Valencia, Bathes in Sunday Clothes,” and “Ten Ten’s Weed Necklace.” They are all young, and they all smile at the viewer. The images are happy and sweet. “Sugar Children” also is ironic. Valentina can be described as a sweet young girl, but she is poor and lives in a slum. Sugar is desired the world over, but do the “Sugar Children” have their fair share? Furthermore, these are the children of slave laborers that produced the sugar.

Muniz’s artistic success continued with photographs of iconic images that he created with unusual materials. “Last Supper, after da Vinci” (1998) was drawn with chocolate syrup, “Medusa, after Caravaggio” (1997) with marinara sauce, “Marilyn Monroe” (2004) with diamond dust, and “Narcissus” after Caravaggio” (2005) was drawn and colored with trash.

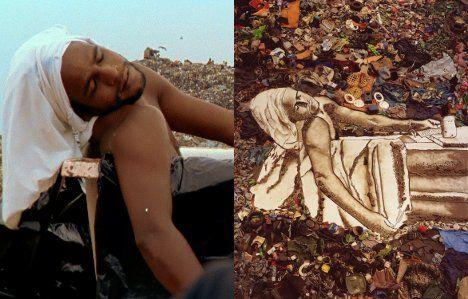

Muniz decided to move back home to Rio de Janeiro in 2008. There he encountered the Jardim Gramacho, one of the largest landfills in the world. Muniz formed lasting friendships with Tiao (Sebastiao Carlos dos Santos), the young leader of the catadores (garbage pickers), and many of the other catadores. The result was a collaboration between Muniz and seven catadores to create art Muniz would then sell, the profits going to the catadores. There were over 1,700 garbage pickers who looked for plastics, paper, and metal, and any recyclable items they could sell in order to buy food and necessities. Their work supported nearly 15,000 people who lived near the landfill.

The left image of the two in “Marat” (Sebastiao) (2008) is the photograph of Tiao in a bathtub Muniz used for his painting. All of the original photographs were shot in an impromptu studio set up in the landfill. The historical painting used here is “The Death of Marat” (1793) by Jacques Louis David. Marat, one of the first leaders of the French Revolution, was assassinated in his bath. Muniz established a large covered space where he could project the photograph onto the floor. He then painted the image in brown tones. The catadores helped to pick and place the trash to form the background. The “Death of Marat” is an interesting choice. Tiao was the leader of the catadores, and he was in effect organizing a revolution. Fortunately, Tiao’s revolution did not end in bloodshed. He became president of the co-op he organized. The Association of Recycling Pickers of Jardim Gramacho now coordinates recycling services in Brazil.

The subject of “The Bearer” (2008) (Irma) (Leide Laurentina de Silva) was a cook for the catadores, preparing food from leftovers found in the landfill. “The Bearer” is a painting on the large studio floor, where all of the portraits were painted. In this piece, trash forms the basket Irma carries on her head. The basket is large, and its weight is increased when one realizes it is made from trash. The Jardim Gramacho had been in operation for 34 years and was almost 300 feet high, covering an area of 14 million square feet. Nine thousand tons of trash were dumped there every day.

Muniz photographed the giant images from above. He found the catadores were generally in good spirits and had developed close bonds of friendship and cooperation: “These people are at the other end of consumer culture. I was expecting to see people who were beaten and broken.” But they are survivors. Irma is a strong, determined and self-confident woman. The images are also poignant and capture a humanity that is palpable.

The ranks of the catadores included very young children and seniors as old as 87. The oldest of the catadores was Vater dos Santos, who knew recycling from bottom to top.. He was described as the resident bard who loved to talk in rhymes and tell moral tales. “Mother and Child” (Suellen) (Suellem Pereira Dias) (2008) represents the young catadores. The composition of the painting recalls Raphael’s “Madonna of the Meadows” (1505-06) that depicted Mary with the young Jesus and John the Baptist. Suellen wears a veil over her head, the baby is wrapped as if in swaddling clothes, and the young boy wears a loose cloak. The expressions on their faces challenge the viewer.

“The Sower” (Zumba) (Jose Carlos da Silva ala Lopez) (2008) is based on Millet’s “The Sower” (1850). Ironically, Millet chose to illustrate the value of hard work at a time when such images were not in favor. Millet’s subject is sowing seeds to feed his family and others. Muniz’s has no seed nor field to plant. However, Zumba happily engages the viewer while standing in the middle of a field of trash. He holds a bag to gather whatever he can find. In fact, Zumba, who had worked as a catadores since he was nine years old, kept all the books he found in the landfill in his hut, and lent them out to others. When the money from this project was returned to the catadores, they used some of it to build a library holding over 7000 books and including an IT room with computers and a learning center.

Muniz took the art to an auction house in London where it all sold. He donated the profits to the catadores. “Marat” sold for $64,000. The catadores were able to purchase a truck, build the library, and buy cell phones, computers, and technology necessary to keep their co-op running.

The project culminated in “Wasteland” (2010), a film recording the three-year process, including interviews with the catadores. The catadores believe the art and the film have helped to change people’s minds about the negative social stigma that existed. Muniz stated in the film, “I’m at this point in my career where I’m trying to step away from the realm of fine arts because I think it’s a very exclusive, very restrictive place to be. What I want to be able to do is to change the lives of people with the same materials they deal with every day.”

“Wasteland” premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2010, and it was nominated for best documentary at the 2011 Academy Awards. Reviews of the film called it “an uplifting portrait of the power of art and the dignity of the human spirit.”

In 2011, UNESCO nominated Muniz to be a Goodwill Ambassador “in recognition of his contributions to education and social development through his artistic career.” In 2015, Muniz started a school of art and technology in Rio de Janeiro for the underprivileged.

The Jardim Gramacho was closed by the Brazilian government in 2012 because of the pollution it caused. The film was largely responsible for this important decision, and the Brazilian government showed it to encourage recycling. Recycling plants were established. The catadores and the company that is harvesting the methane gas from the landfill negotiated severance pay of 11 million dollars to be distributed to the workers.

Muniz once observed, “A lot of time you keep looking for beauty, but it is already there. And if you look with a little bit more intention, you see it.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.