Romaine Brooks was an American citizen; however, she was born in Rome, spent her childhood in New York, went to finishing school in Switzerland, pursued her artistic carrier in Paris, Italy, and Capri, and she died in Nice. Hers may appear to be a charmed existence, but Brooks experienced much tragedy in her early life. Her father was a descendent of Napoleon, he also was an alcoholic who abandoned his family. Her mother was an heiress to a Pennsylvania coal mining fortune. She also was mentally disturbed, emotionally abusive to her three children, and left them with the laundry lady with no money, she did let Romaine draw. Brooks’ brother St Mar was mentally disturbed. Romaine was the only one who could calm and control him, and he became her responsibility. Brooks’ mother left Romaine and her sister Maya the estate in 1892 when Romaine was eighteen. In 1902 both her brother St Mar and her mother died, allowing her freedom for the first time. Romaine Brooks was a survivor, and she determined what and who she wanted in her life.

Brooks enrolled in the Academie Colarossi in Paris to pursue her love of art, but she only remained there from 1898 until 1899. The only woman in the class she was harassed by the male students and raped. She gave birth to a baby girl who she left with a convent. She then studied voice in Paris to have a career in opera. She did sing in a cabaret, but she made the decision to focus her career in art. Her choice of friends and lovers were often women, with the exception of John Ellingham Brooks, an English writer who was homosexual. Their marriage in 1903 was a “White Marriage,” that eventually ended in divorce. She gave John an allowance until he died; she also kept her married name Brooks.

By 1903 Brooks had cut her hair short and began to wear men’s clothing that she designed. She became a part of the Parisienne “haut monde” (high society). Brooks lived her life and painted in shades of black through gray to white, with touches of umber, ochre, and alizarin. Her apartment was decorated with white furniture and floor tiles, and gray walls with touches of beige and accents in black. It became the rage in interior décor. Her minimalist aesthetic was shared with “Madame Errazuris” (1908-10) (94”x58”) (SAAM). Errazuris, already an influential interior designer. She was a major patron on modern art, and a leader of Paris style from 1880 into the early part of the Twentieth Century. For the portrait, Brooks used her limited palette of black to white, with touches of ochre, umber, and alizarin (crimson). Madame Errazuris wears haute couture. Her black dress and long jacket are trimmed with white braid and tassels. Her white blouse and beige scarf, large black feathered hat with veil, and black umbrella with alizarin trim, and alizarin gloves match her hair. Brooks has placed her in front of an indistinct, lightly mottled ochre background and mottled umber and alizarin ground. To create a sense of space, a rough partial petition wall is placed at the left. Unlike most portrait paintings that include specific objects to establish the character of the sitter, Madame Errazuris is a singular image. She is self-assured and looks directly at the viewer. No other accoutrements are necessary

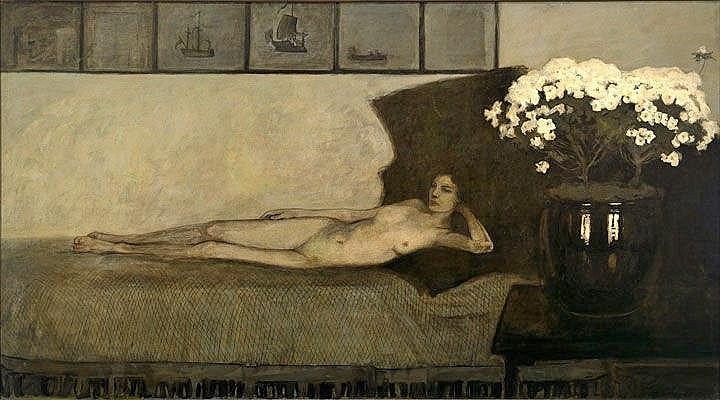

Brooks had her first one-person exhibition at the Gallery Durand-Ruel in Paris in 1910. “White Azaleas” (1910) (59” x 107”) (SAAM) was one of thirteen paintings in her exhibit, and it was the sensation of the show. A woman painting a nude woman was anything but usual, and the sensitivity Brooks depicts in the female form is both exotic and erotic. The nude figure is stretched out comfortably on a bed with her head supported by large black pillows. A black table holds a large black Chinese lacquer planter with two white azalea bushes. The only touches of white can be found in two windows reflected in the planter, the mass of white azalea blossoms, and one white blossom at the upper right of the bunch.

The composition has much in common with Japanese wood cuts that Brooks liked. On the wall above are six framed images, but only three are clear. The first is a small row boat, the next a ship under sail, and the third a ship with the sails down. The ships have been interpreted in several ways as Brooks’ life had many angles. The idea often expressed is that the nude, who ignores the viewer and stares thoughtfully ahead, maybe thinking about an escape from her life.

“White Azaleas” was compared to Goya’s “Naked Maja” and Manet’s ”Olympia,” but these paintings were by male artists who gazed at the nude female, a long and acceptable tradition. Brooks commented on her intent: “I grasped every occasion no matter how small, to assert my independence of views. I refused to accept slavish traditions in art, and though aware it would shock, I insisted on marking the sex-triangles of all my female nude figures….” Comte Robert de Montesquiou, Symbolist poet, art collector, and DANDY famously called Brooks “a thief of soul.”

From 1911 until 1914, Brooks was in a lesbian relationship with Ida Rubenstein, a famous Ukrainian actress and dancer. Brooks created several paintings of Rubenstein including another nude image, suspended and seeming to float in air, and a second similar painting as Venus. Brooks referred to these nude images of Rubenstein as “some heraldic bird delicately knit together by the finest of bone structure, giving flexibility to curveless lines.” “The Cross of France” (1914) (46” x 33.5”) (SAAM) reveals another aspect of their life together. Both worked for the War effort. Brooks was an ambulance driver. The three-quarter portrait, typical of her paintings, depicts Rubenstein dressed as a Red Cross nurse. She stands in front of a war-torn landscape with the town of Ypres in the distance burning. It is a stark and serious image and pays tribute to all who worked for the war effort. The painting was displayed in a Paris gallery in 1915, with an accompanying flier and a print of the painting. A poem by Gabriele D’Annunzio, an Italian writer, playwright, journalist, and aristocrat who escaped to Paris and was taken in by Brooks, accompanied the image. The pamphlet was sold to patrons, the proceeds going to the Red Cross. Rubenstein wanted to buy a farm in the country where they could live, not something Brooks wanted. Although Brooks painted Rubenstein again, their relationship ended.

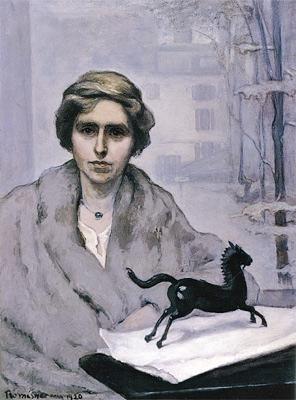

In 1914, Brooks met Natalie Clifford Barney an American expatriate, playwright, poet, novelist, and openly lesbian. Their loving relationship lasted for fifty years, although both had other short relationships and were also part of a long term “manage a trois.” Each was financially independent and lived openly, and flamboyantly outside of traditional norms, although they maintained separate apartments. “Miss Natalie Barney, L’Amazone” (1920) (116.5’ ’x 157.5’’) (SAAM) is one of many portraits Brooks painted of Barney. Barney sits in front of a window in her Paris apartment, where her famous Salons were held. Only a sliver of her apartment is depicted at the left, but the view out the window depicts a snow filled tree and images of the town houses across the street in a snowy haze.

Cloaked in a gray fur coat, Barney sits at a black table covered by the folded page of one of Barney’s manuscripts. Placed on the white page is the statue of a racing black horse. A personal touch added to illustrate Barney’s love of riding, something she did astride. Brooks sometimes included animals in her portraits to reflect the character of the sitter. Racing horses were also symbolic of and a tribute to personal freedom, an attribute that certainly reflects both Brooks and Barney. The horse was included as a reminder that Remy De Gourmont nicknamed Barney L’Amazone, to describe Barney’s powerful female presence in the life of Paris.

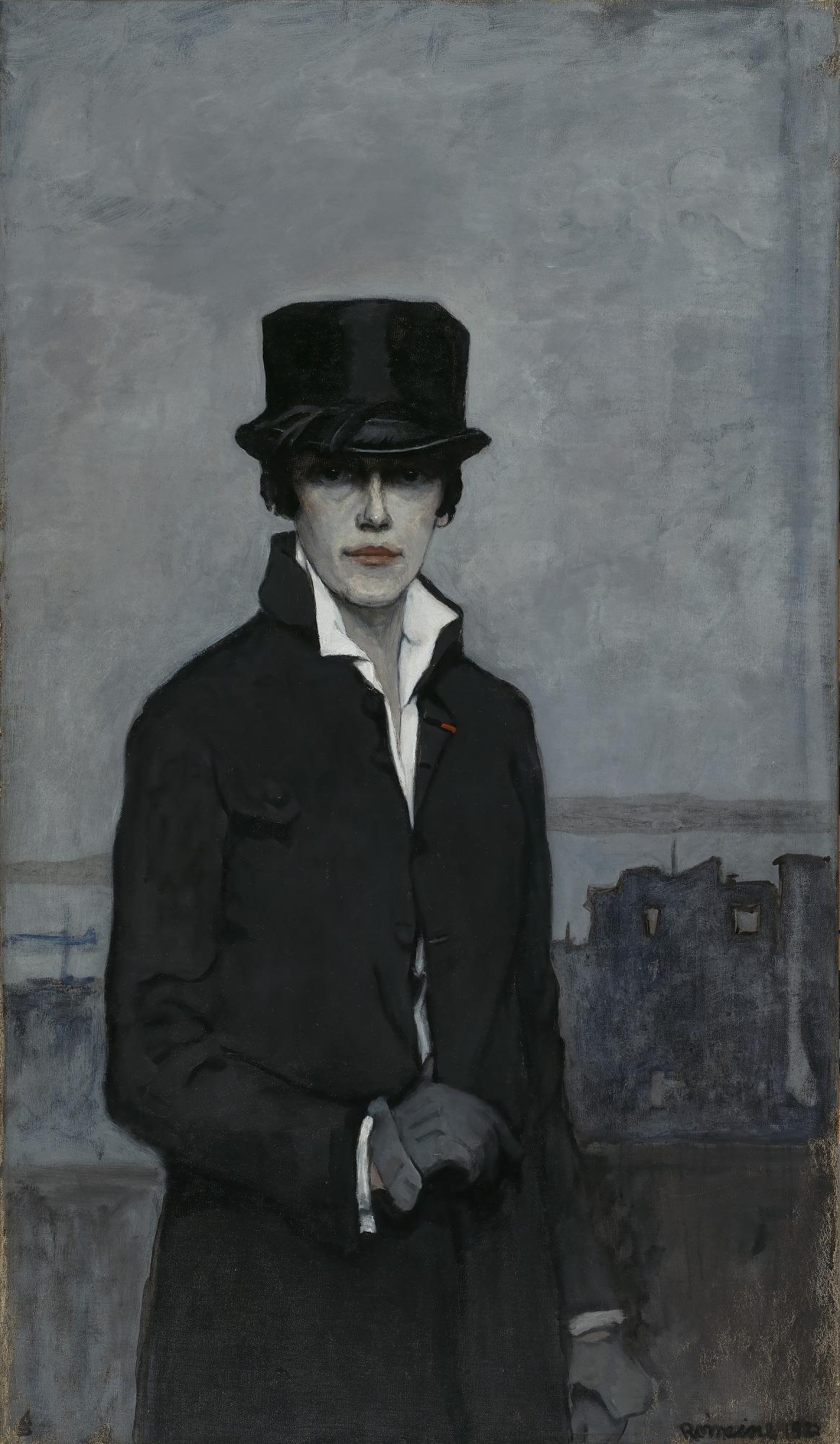

Brooks frequently painted self-portraits. One of the most famous is her “Self-Portrait” (1923) (46” x 47”) SAAM). Brooks is dressed in elegant fashionable clothing that she designed. Her well-cut long black coat opens at the neck to reveal a crisp white shirt collar and at the cuff of the sleeve the appropriate amount of white cuff. The outfit includes gray leather gloves and a flat top hat that purposely shades her eyes. Behind is a wall, and beyond it the suggestion of a ruined building on the shore of lake with land beyond. The sky above divides the composition in half. It is a gray day, the clouds a blend of grays and blues seen in the landscape.

Two touches of alizarin are noticeable: Brooks’ lipstick, near the center of the painting, and below to the right the red pin on her jacket. It is the French Croix de la Legion d’Honneur, awarded to Brooks in 1920 in recognition of her heroic work during World War I. The Croix d Honneur was created by Napoleon in 1802 to be presented to persons in the military or to civilians whose work brings honor to France through scholarship, arts, science, or politics.

Born into the French aristocracy, Elisabeth de Gramont, called Lily, was the third woman in the ”menage a trois.” In the painting “Elisabeth de Gramont” (1924) stands front of a castle painted in tones of light grays and beiges. A high wall and impressive stairs lead up to an arched entrance and a display of tall windows. Inspired by Japanese wood cuts, Brooks painted twisting, silhouetted trees. Lily is posed in Brook’s favorite three-quarter view, and her image takes possession of the space. Her red- brown jacket with button cuffs has a black velvet collar. It is well tailored in the popular androgynous manner. Her high-collared white blouse with large ruffles, is a nod to feminism. A large red flower is pinned to her jacket. Lily was a tastemaker of her time, and her clothing and pose tell that story. She famously said, “Civilized beings are those who know how to take more from life than others.” She was strongly associated with feminist causes, but was nicknamed “Red Duchess” for her support of socialism. However, on visiting Russian and seeing communism in action, she changed her mind.

Although Brooks was part of the social scene is Paris she traveled frequently. Her persona was the subject for several literary characters including Ventia Ford in Radclyffe Hall’s The Forge (1924) and Olympia Leigh in Compton Mackenzie’s Extraordinary Woman (1928). Tired of the social scene she left Paris for Italy in the 1930s. Brooks and Barney built a home in Italy that they shared in the summer. They jokingly called the Villa trait d’Union (Hyphenated Villa), because of its two separate wings that were joined by the dining room. During WWII Brooks protected Barney, who was partly Jewish, from the Nazi’s.

Brooks had several exhibitions of her work, the last major ones in Paris, London, and New York in 1925. During the years in Italy, she wrote two unpublished autobiographies, and she drew over 100 automatic line drawings to be included in the books. Automatic line drawings were developed by surrealists on Freud’s theory of the unconscious, and were accomplished by drawing with a pencil or pen an undetermined, spontaneous single continuous line.

During the 1950s and 60s, she began to have eye trouble and became paranoid. She cut off all relationship with Barney, although Barney continued to write to Brooks. Brooks died in Nice in 1970 at age of ninety-six. Her autobiography No Pleasant Memories was published posthumously and refers mostly to her unfortunate childhood. Whitney Chadwick, author of one of the first important books on women artist (1990) wrote that Romaine Brooks was “a new image of the noble and independent lesbian.” In Brooks’ self-portraits and portraits of her friends and associates, independence and pride are on full display.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.