Rev. Marguerite Morris fought for her daughter, Katherine Sarah Morris, for nearly a decade.

Katherine died in 2012 after charcoal grills were lit in her car. Marguerite Morris said she was a “victim of marital fraud, and worth $100,000 dead.”

Katherine’s manner of death was ruled a suicide. The cause: carbon monoxide toxicity.

Marguerite said there was no investigation.

“Katherine’s death certificate was signed on May 6, 2012,” she said before the House Health and Government Operations Committee in February. “She died May 6, 2012. Her death was ruled a suicide on May 6, 2012.”

Marguerite Morris submitted a request to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner asking that her daughter’s manner of death be changed to undetermined to allow for an investigation. But her request — and subsequent appeal — was denied.

She took the state to court three times and was finally granted an administrative hearing in 2020. But even then, she said, the state tried to put a halt to the proceedings, citing a decades-old inconsistency in the law.

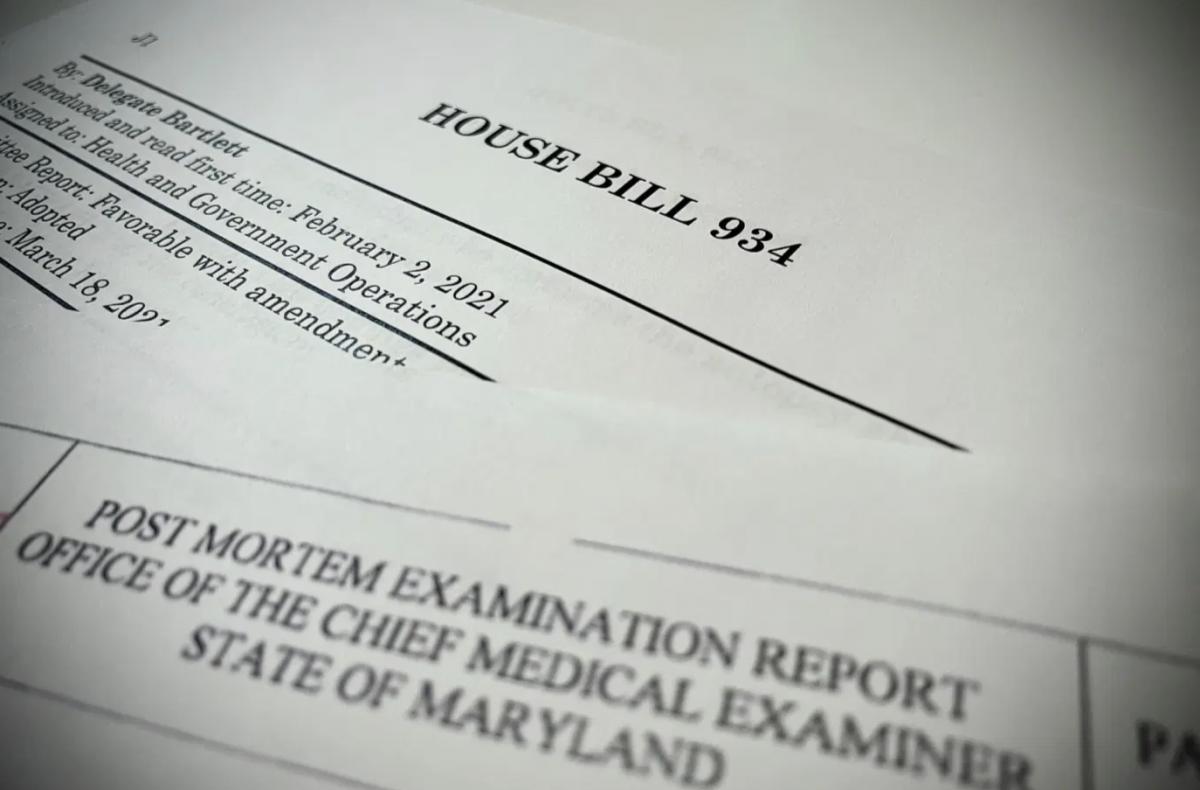

A bill sponsored by Del. J. Sandra Bartlett (D-Anne Arundel), will fix that inconsistency.

Beginning Oct. 1, families can file an appeal to the secretary of the Department of Health if the chief medical examiner denies their request to change the manner of death on their loved one’s autopsy report.

The bill was enacted without a signature from Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. (R) last weekend. Prior to its passage, Maryland law allowed only the cause of death to be appealed if requests were denied.

“I would … like to emphasize that the cause of death is not the manner,” Morris said. “The cause is scientific, and the manner is evidentiary.”

One successful appeal

The cause of death is a specific event, like asphyxiation or heart disease, that causes a person to die. Medical examiners can rule a manner of death as an accident, suicide, homicide, natural causes or undetermined.

After the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner files its conclusions on the cause and manner of death, families have a 60-day window to request that they be corrected if they feel there are inconsistencies.

Homicide rulings are not able to be disputed.

Should the chief medical examiner rebuff the request, under Bartlett’s bill, families can appeal to the secretary of the health department, who can grant an administrative hearing.

If an administrative law judge determines that the cause or manner of death should be changed and the secretary of health declines to do so, families can appeal to the circuit court.

Dr. David Fowler was the chief medical examiner at the time of Katherine’s death. He served as acting chief medical examiner in 2001 before taking the position permanently in 2002.

He left the role in 2019.

According to Maryland Department of Health spokesman Charles Gischlar, 22 appeals to have the cause or manner of death on an autopsy report changed were filed from 2001 to 2019. Only one appeal was successful.

Fowler, a controversial figure, is currently a defendant in a wrongful death lawsuit filed by the family of Anton Black, a 19-year-old who died in police custody in 2018 in Greensboro. Black’s manner of death was ruled an accident.

Attorney General Brian E. Frosh (D), who announced in April that his office plans to audit in-custody death determinations made under Fowler, has received criticism for representing him in the lawsuit filed by Black’s family.

In a phone interview, Sonia Kumar, a senior staff attorney for the ACLU of Maryland, said that Black’s family did not submit a request to change the findings of Anton’s autopsy report, and she’s unaware how the ability to do so is communicated to the bereaved.

“My guess is that a lot of families aren’t even made aware of it,” Kumar said.

“A loophole”

Government agencies have been aware of the inconsistency in appeals since the law was enacted in 1992.

In a May 1992 letter to Gov. William Donald Schaefer (D), former Attorney General J. Joseph Curran Jr. (D) suggested that these “apparent inconsistencies be resolved next session in clarifying legislation.”

But they weren’t until Bartlett successfully sponsored the bill this year.

Marguerite Morris said that the state has used the inconsistency against her.

“It was about a word that was missing that the state was using as a loophole” to deny me an administrative hearing, she said during a phone interview Tuesday.

But Morris has seen success in 2021: An administrative law judge issued the opinion that Katherine’s manner of death be changed from suicide to undetermined in March.

The state is appealing this ruling at a hearing later this month.

Morris was also relieved to learn that Hogan will allow the law to go into effect without his signature.

“I’m glad to hear that, that was really, really good news to hear,” she said. “That law that is now being enacted … will help other families.”

But her fight isn’t over. Morris said that she hopes to work with legislators during the 2022 session to have the 60-day time limit on requests to change autopsy reports repealed.

“It’s just so unfair because you just don’t have answers that quickly,” she said.

Kumar agrees.

“There’s this way in which, to me, it feels unreasonable to put the burden on the family — particularly in such a short time period,” she said. “They may be disturbed by the [Office of the Chief Medical Examiner’s] conclusion but may not be aware how far-reaching the consequences are of those … conclusions.”

By Hannah Gaskill

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.