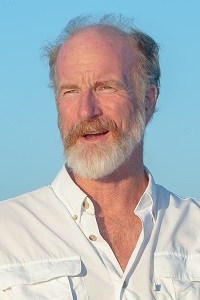

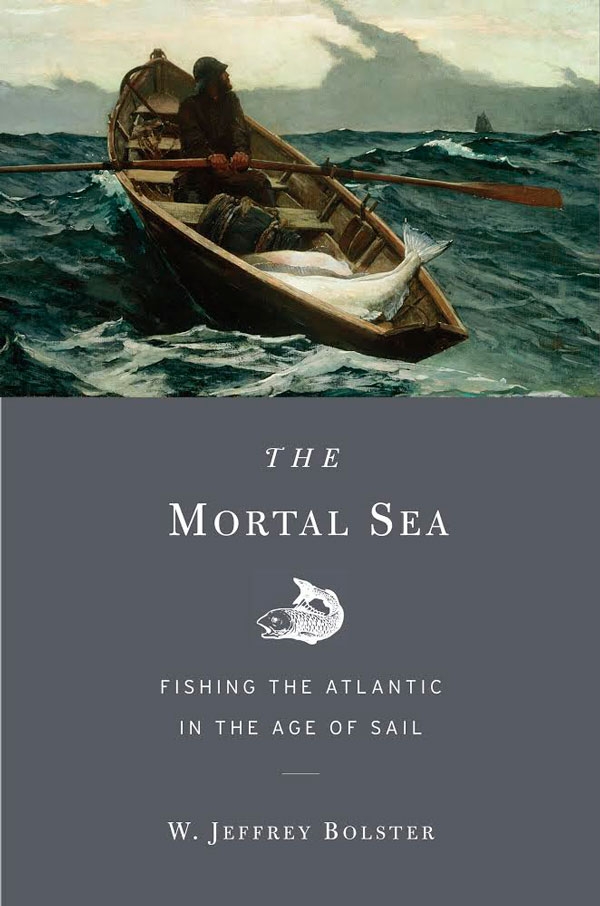

Author Jeffrey Bolster will highlight Chestertown’s Downrigging Weekend with a talk at the Garfield Center for the Arts at 8:00pm on Saturday, November 1. Bolster will be discussing his current book, The Mortal Sea-Fishing the Atlantic in the Age of Sail, winner of the prestigious 2013 Columbia Bancroft Prize awarded annually for excellence in writing about history and diplomacy.

Author Jeffrey Bolster will highlight Chestertown’s Downrigging Weekend with a talk at the Garfield Center for the Arts at 8:00pm on Saturday, November 1. Bolster will be discussing his current book, The Mortal Sea-Fishing the Atlantic in the Age of Sail, winner of the prestigious 2013 Columbia Bancroft Prize awarded annually for excellence in writing about history and diplomacy.

The Mortal Sea is a historical account of the human impact on the sea from the Vikings to the industrialized fishing in American waters.

Harvard University Press describes the book as, “Blending marine biology, ecological insight, and a remarkable cast of characters, from notable explorers to scientists to an army of unknown fishermen, Bolster tells a story that is both ecological and human: the prelude to an environmental disaster. Over generations, harvesters created a quiet catastrophe as the sea could no longer renew itself. Bolster writes in the hope that the intimate relationship humans have long had with the ocean, and the species that live within it, can be restored for future generations.”

The Spy asked Professor Bolster 5 questions and he graciously answered (in less than an hour via email I might add!). We look forward to his visit.

Q: I’ve enjoyed researching you a bit and look forward to your talk during Downrigging Weekend. I see that you were acquainted with the ocean at an early age and went on to work and captain many types of ships. Can you tell us a little about your first profound ocean experience?

Thanks. In 1975, the summer after my junior year of college, I was hired as skipper on the Alden schooner, Niliraga, a private yacht sailing out of Northeast Harbor, Maine. She was 42 feet on deck, about 56 feet sparred length, with her bowsprit and overhanging main boom. I thought I had died and gone to heaven. What a cool job. But I had big shoes to fill. Her skipper for decades had been Ralph Stanley, Maine legendary boat-builder whose specialty was lobster boats and Friendship sloops. By the mid-1970s Ralph’s building business had taken off so that he could no longer afford the time to run Niliraga. I felt like Christopher Columbus that first evening underway: what a thrill. I sailed her as far west as Boothbay Harbor and as far east as Roque Island, the “holy grail” for cruising sailors in those days. We had a compass, a depth sounder, and a static-dominated old radio direction finder, in addition to our ears and eyes and a watch – all fine tools for sailing the foggy coast of Maine. So I was hooked, and a year or so later, after finishing college, I bought a one-way plane ticket to the British Virgin Islands so I could get on a bigger schooner, and then a better schooner after that. For the next ten years I followed the sea on a variety of vessels, almost all commercial, auxillary-sail vessels, and I was privileged to sail as skipper on quite a few stunning schooners in both coastal and offshore service.

Q: Your early book, co-authored with Hilary Anderson, “Soldiers, Sailors, Slaves, and Ships: The Civil War Photographs of Henry P. Moore”—how did you come across Henry P. Moore and why did you find him compelling?

Henry P. Moore was a native of NH, and one of the best-known photographers of the Civil War. No one had ever assembled all of his work in one place, so the Curator and Director of the NH Historical Society decided to do an exhibit on Moore and his work. This was in 1998, and scanning technology was just becoming available, so the idea was to physically collect all the Moore photos from around the country, and then scan them, in addition to hanging an exhibit and publishing an exhibition catalog. My first book, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail, published by Harvard Univ Press in 1997, had gotten some attention, so I was asked by the NHHS to participate in the project as a researcher and writer. It was a great public history project, and I was honored to be part of the collaboration, but it was a pretty minor chapter in my overall career.

Q: Your current book takes on a subject that has significant environmental themes. Were you surprised at what you learned about the degradation of the sea during your research?

I had a hunch before I began that I would find significant human impact on the living ocean prior to industrialized fishing. It turns out that my hunch was really good. The impact was much greater than I had imagined. I thought that if I could document the fact that people had affected the living ocean using really simple gear – hook & line, hand-held harpoons, rowboats and sailboats – it would make the case that with the technology at our disposal now, and in the future, the fish don’t have a chance. Ultimately I was surprised to learn that we as a society have been having the same “discussion” about degraded fisheries since just prior to the Civil War! And I was also surprised to learn that fisheries regulations, to prevent overfishing, had been tried in different ways and different places since the 1630s – yes, the 1630s. The federal govt first regulated ocean fisheries to try to prevent depletion of mackerel in the 1880s. So the idea that “regulation” by the govt is a recent imposition is just pure nonsense. Americans have known for a very long time that we have been handling our fisheries in unsustainable ways.

Q: Are you able to tell us anything about a current project. And will you be returning to more civil war subjects?

Probably not any more Civil War subjects. I am primarily a maritime historian. For the last year or two I have been writing magazine articles on sailing subjects, and some historical ones.

Q: Are we farther along in being sensitized about the ocean’s desperate condition, and how could the average person help?

Somewhat more sensitized, for sure. The average person can avoid putting fertilizer on their lawn. What a silly idea – to dump excess nutrients into the Bay so we can have green grass! We could all use less plastic. For instance, single use plastic bags and single use plastic water bottles and soda bottles should simply be illegal. Plastic is a wonderful material and has some applications in the world, but right now the oceans are riddled with tiny plastic fragments, the remnants of our consumer society. In some parts of the Sargasso Sea a plankton tow can come up with equal weight of plastics and plankton. What are the implications? We don’t really know: this scourge is new. Average people can eat some seafood for sure, such as lobster, mackerel, mussels, oysters, and other species whose populations are OK, and which are harvested sustainably, even as they avoid purchasing or eating species such as Blue Fin Tuna. Those fish are like Siberian Tigers, noble apex predators threatened by human activity.

I’m looking forward to being back in Chestertown.

Cheers, Jeff Bolster

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.