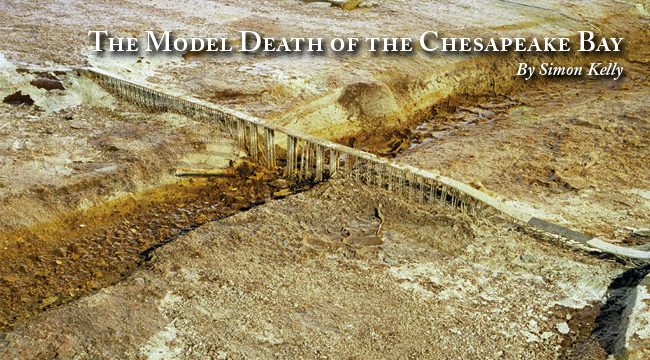

[slideshow id=49]These images, kindly made available to The Spy by the Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI), at a first glance may resemble the canals of Mars or perhaps part of a sci-fi movie set. Taken circa 1998, the photos are actually the last impressions made available to the public of the then disintegrating and now totally obliterated Chesapeake Bay Hydraulic Model. The photos would go on to be featured in a presentation at the CLUI’s Los Angeles exhibit hall in March and April of that same year, their subject, and the building housing it, however, would only face more dilapidation, roof collapses, and a series of uneasy exchanges and proposals between private investors, Queen Anne’s County, and the state of Maryland.

As recently as December of last year, according to a report in the Capital, the Matapeake Facility, where the bay model’s crumbling remains are interred, may be the future site of Miltec Corp, a U.V. curing operation. There have even been murmurs of an 80,000 square foot sports complex being developed alongside the Miltec business. But with official statements relating the site’s future vague at best, the one thing that does remain certain about the Matapeake facility is that its days as an epicenter for hydrological research on the bay are long gone, if not entirely wiped from the public memory.

So what is hydrological research you might ask, and why is it important at all? Well, it all started with a man named Rogers C.B. Morton, the 22nd United States Secretary of Commerce, the 39th Secretary of the Interior, a member of Maryland’s 1st Congressional district, and a resident of Talbot County. It was the 1960s, and for the first time, people were becoming aware of the increasing amounts of pollutants flowing into the bay. Commercial fishing was taking a blow, along with people’s ability to enjoy a day at the beach. In 1965, as Morton was rounding out his second year in congress, he spearheaded the Chesapeake Bay Basin Study, a $6 million program, which in Morton’s words, was intended “to make a complete investigation and study of water utilization and control of the Chesapeake Bay Basin.”

It would be another eight years before construction on the hydraulic model would begin, by which point Morton would have already been appointed to his post as Secretary of the Interior by Nixon. According to a report released by the CLUI that accompanied the photographic exhibit, much of this time was passed debating over whether a physical model was necessary in the first place. By 1967, MIT had been called into the discussion, their suggestion being that a numerical model would prove to be cheaper and more effective than the sprawling physical models the Army Corps of Engineers had already built for the Mississippi River Delta and the San Francisco Bay in the 50s. Despite this sound mathematical reasoning, however, the Army Corps won out the bid, and by 1975, bathymetric readings of the bay were being taken in order to lay the models foundation inside the old ferry terminal on Kent Island.

Between 1973 and 1978, around $15 million would be spent to get the model up and running. Covering eight of the Matapeake Ferry Terminal’s sixty acres, the model replicated the actual bay and all of its tributaries, from the Susquehanna down to the Atlantic headbay on a 1:1,000 scale. That’s 4,400 square miles distilled, condensed through geometric ingenuity into a dusty and even then, crumbling old warehouse. To make the microcosm more complete, time was also scaled down; 15 years of real time on the bay could be simulated in just 19 days on the model. Control of the temporal, as well as the spatial dimension of the bay was of great utility to the researchers, because it allowed them to project the effects of various factors on bay health well into the future. To run just one test on this thing (and that meant calibrating everything from current speed to salinity), it took a team of 20 people, some of them hydraulic engineers, some computer analysts operating machines primitive by today’s standards that ran the model’s tidal generators and collected data on miles of magnetic tape.

And yet, for all of the ambition and romance of this model, by the time it was opened to the public in 1978, it had become hopelessly outmoded, and was not really producing the quantity or quality of results expected of it. Arguably always a work in progress, in the over ten years that it took for the model to reach peak operational status, advances in computer science made the site little more than a public works novelty.

The CLUI’s report, from which the bulk of this article has been informally comprised, makes the point that in spite of the numerous setbacks faced by the model and its crew, the experiment did, by 1981, when operations became suspended indefinitely, have something to show for itself. This excerpt details the bulk of the model’s most concrete findings and achievements,

“One study was conducted to determine the effects on the ecosystem of diminished freshwater inflow to the bay due to increased ground water draw from development. Field data from a period of drought was used to project conditions for 50 years into the future, given current rates of development. Another test was a high flow and low flow test on the Potomac River, to determine if the effluent from a sewage treatment plant would circulate out of the river and find its way to the ocean[…] Some of the data from the model was used in the development of the computer models for the bay…”

So, while posterity may remember this project as little more than an anomalous, colossal misuse of public funds, there is still something truly wonderful and awe-inspiring about the idea of state technicians in white coats and horn rimmed glasses peering into a miniaturization of the largest estuary in the North Atlantic. Described by the CLUI as a “titanic analog to the emerging digital age”, the Chesapeake Bay Hydraulic model in many ways marks one of the rare moments in large scale research when the pursuit of data runs headlong into our innate tendency to tinker, to play. Like kids making sandcastles with moats at the beach, the researchers at the Matapeake site must have seen the wave of the information age coming, yet they plugged on doggedly with their model, their labor of love, until the chunks of the warehouse ceiling that had been falling out all along became too numerous to remove, the cracks in the leaky concrete foundation too wide to patch. The model was officially closed to the public by February of 1983.

Some 120,000 people visited the Chesapeake Hydraulic Model while it was still open. Were you or someone you know one of them? If so, please feel free to send impressions, memories to [email protected] or share on the comments section. There is still more, much more to be said. Those interested in reading the CLUI’s report in full and checking out one of the more interesting NGO’s around, try this link

Sarah L. says

The photos are weirdly fabulous–the distorted sense of scale is quite disconcerting. I’ve always been intrigued about that place. Thanks for the story, Mr. Kelly!

Mary Wood says

I remember visiting the model . It made me realize the large area that drained into “our’ Bay. My husband was already concerned about the development on Kent Island and what it might do to the water table.

jim y says

I remeber going ther on a school trip, and over the years wondered what had become of it

Bill Kille says

On my one and only visit I remember thinking the place was an amazing waste of money.