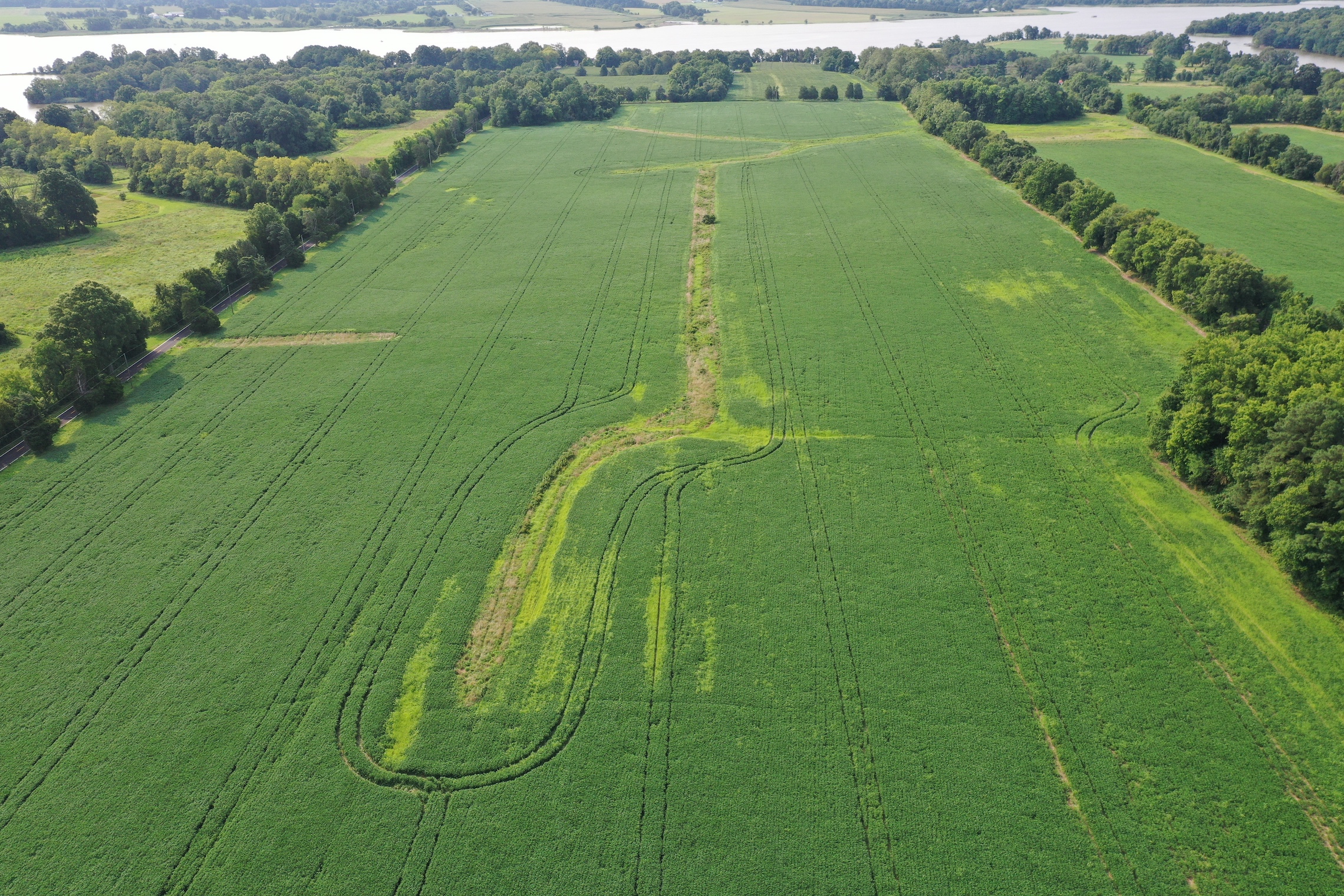

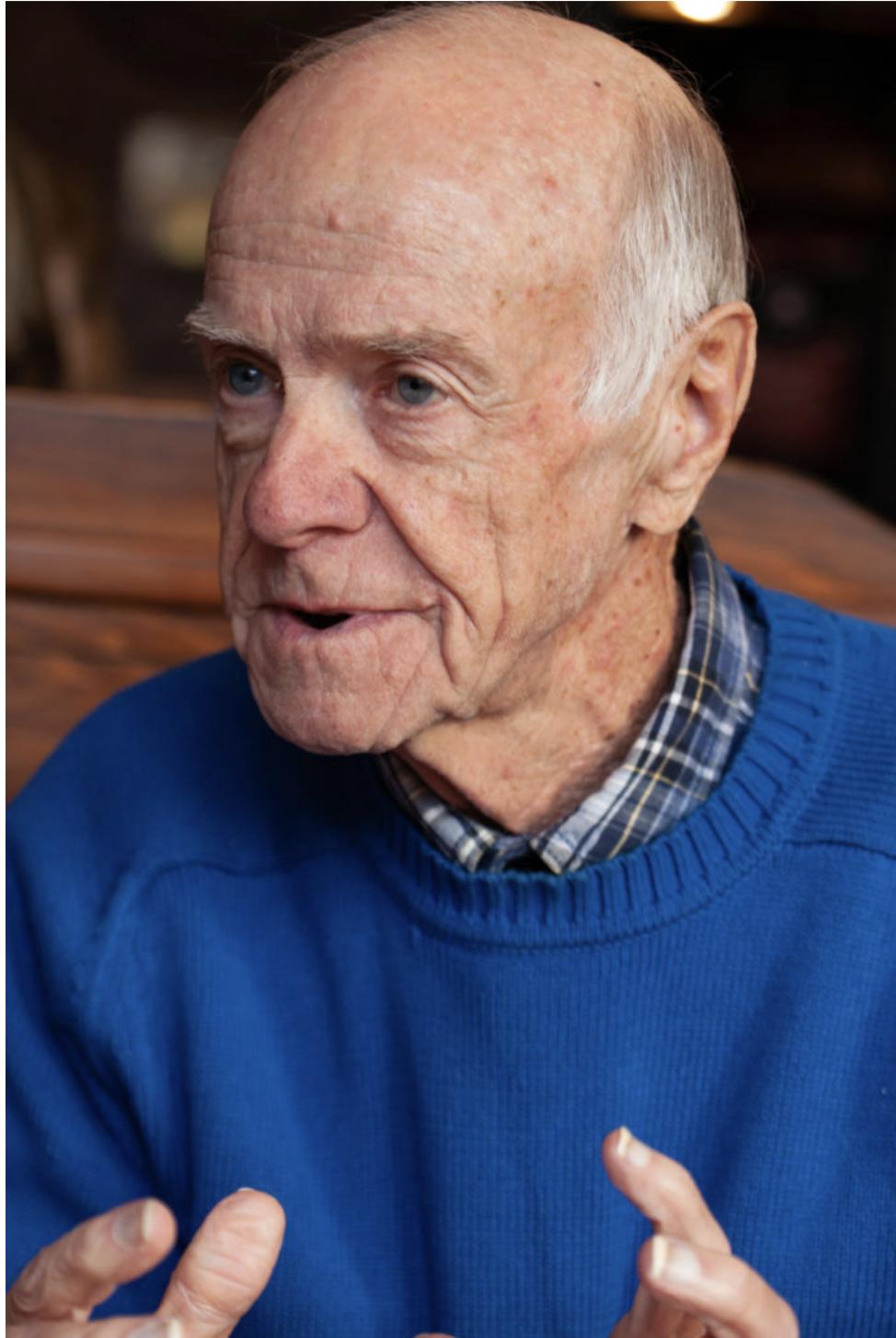

When Doug West’s father bought a 106-acre grain farm almost thirty years ago, his hope was that the farm would be preserved. Today, Doug and his wife Sue, the Maryland Environmental Trust, and Eastern Shore Land Conservancy are thrilled to announce that the entire West Farm is under a conservation easement thanks to the West family’s generous donation. “The best part is keeping it as such,” says Sue. “I like the psychology of saying: ‘What is it that you honor and love and would miss?’” For the Wests, the answer to that question is the peaceful grain fields and woodlands of their Kent County farm, now protected forever.

Bridging two other ESLC easements in Quaker Neck, a Chestertown area with rich Quaker history, the new easement protects both working cropland and non-tidal forested wetlands which are now part of a contiguous habitat for forest interior dwelling species of birds (FIDS). These bird species require large connected blocks of forest in order to breed safely and successfully after their long migration from South and Central America. According to the Maryland DNR, “The key to maintaining suitable breeding habitat for FIDS, and halting or reversing their declines, is the protection of extensive, unbroken forested areas throughout the region.”

This newly connected stretch of protected land also ensures that the lush rural scenery of Quaker Neck Road will remain the same for centuries. Although, there is one recent addition. In amongst old storybook cedars, mighty oaks, and poplars, the West Farm is home to a young peach tree from the family home where Sue was raised, also in Kent County. After processing a few bushels of family peaches one year, Sue noticed 30 peach tree saplings coming up in the West Farm compost pile. Most were given away, and one was planted on the farm, where it’s already begun to bear fruit—a testament to Kent County’s long history of orchard production and a fitting image of how the West’s conservation easement will continue to benefit their community, not only through tree saplings, but through mindful safekeeping of wildlife habitat, local agriculture, Quaker Neck’s historic and peaceful sense of place, and the local waterways which Doug has personally spent 25 years stewarding through his work planting oysters with Horn Point and the Oyster Recovery Partnership. “Kent County is not going to preserve itself,” Doug shared. “You’ve got to fight for it to happen. If you don’t work to keep it preserved, it will go the other way.”

This easement would not have been possible without both the West family’s priceless donation to conservation and Maryland Environmental Trust’s long-term partnership and technical expertise.

To learn more about conservation easement programs please contact ESLC’s director of land conservation, David Satterfield, at [email protected]. And to learn more about funding for restoration of non-tidal wetlands, please contact ESLC’s enhanced stewardship manager, Larisa Prezioso, at [email protected].

###