Freshwater mussels play an amazing yet little-known role in healthy rivers and streams in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. As their numbers dramatically decline we must now focus on restoring mussel populations, according to a report issued this week. The report comes from a workgroup of experts under the EPA’s Chesapeake Bay Program. It lays the groundwork for expanding mussel restoration in the Chesapeake Bay watershed with a growing coalition of advocates and scientists across the region.

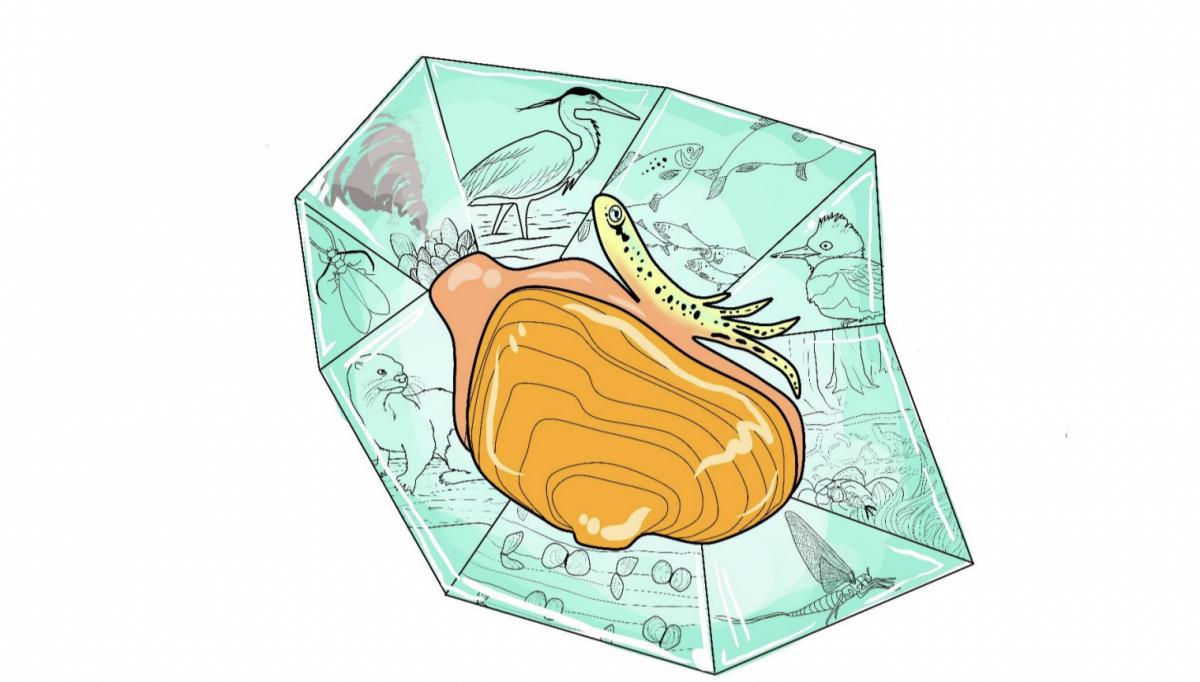

About 25 species of mussels live in the freshwater rivers and streams that flow into the Chesapeake Bay. They are found across the watershed, from tidal rivers to mountain streams in Virginia, Maryland, West Virginia, New York, and Pennsylvania. A single mussel can filter up to 15 gallons of water per day, which can prevent pollutants such as nitrogen from flowing downstream, leading to clearer and cleaner water. Mussel beds create habitat for small aquatic creatures, which in turn become food for fish.

“Freshwater mussels really are unsung heroes in Chesapeake rivers and streams. But as their populations plummet, I’m afraid we could lose some mussel species before we fully understand their benefits,” said Chesapeake Bay Foundation Virginia Senior Scientist Joseph Wood, Ph. D., who is the lead author of the report.

More than half of all freshwater mussel species are now facing extinction. Mussels are threatened by pollution, dams, climate change, disease, and loss of habitat. The report estimated that mussel populations in the Chesapeake Bay watershed have likely fallen by 90 percent since European colonists arrived in the 1600s. This decline has meant a dramatic loss of both mussel biodiversity and benefits in reducing pollution. Recent research shows that some mussel species are experiencing pressures from viruses we are just learning about.

“There’s a growing enthusiasm for protecting and restoring freshwater mussel populations in the Bay watershed,” said Wood. “But to bring back mussels we need commitment, leadership, and investment.”

Restoration of a better-known Chesapeake shellfish could serve as a model for freshwater mussels. After Bay oyster populations collapsed in the late 20th century, efforts to build reefs and plant them with oysters are showing substantial promise in some Bay tributaries.

“Just like oysters in the 1980s, freshwater mussels are on the brink of catastrophe,” said Wood. “Oyster restoration experience can inspire work with mussels as well. We must ensure clean water and good habitat in key waterways, as well as stock shellfish to boost the population.”

As with oysters, successful mussel conservation and restoration depends on the growing coalition of partners in the Chesapeake watershed working on the issue, including the U.S. Fish Wildlife Service.

“Many organizations are building momentum towards propagating and restoring mussels in our region, but freshwater mussels remain in dire circumstances. The future of clean, diverse waterways depends on this work,” said Rachel Mair of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, who leads mussel restoration efforts at Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery in Virginia and is a co-author of the report. “Research and investment in mussels create huge benefits for rivers and streams in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.”

The fascinating life cycle of mussels begins when their larvae attach to the gills of fish for a few days or weeks. To accomplish this, some mussel species trick fish into attacking lures sprouting from between their shells. These lures, which look remarkably like bait fish, are packed with mussel larvae that fill the water when disturbed. The larger fish spread the mussel larvae to new areas.

Restoring mussel populations is challenging given the many different species and their complex life cycles. Many mussels rely on just a single species of fish to reproduce, and mussel hatcheries must raise fish to serve as hosts for breeding mussels. Fortunately, recent advances in propagation techniques are showing success at facilities such as Harrison Lake. But insufficient funding of monitoring, research, and restoration has held back efforts.

Maryland recently began several pilot restoration projects to monitor and augment mussel populations in the Bay watershed.

“We are excited to work with the private sector and non-profits along with state and federal partners on projects to improve our local populations of freshwater mussels because there is typically a limited amount of grant money available to support this type of work,” said Matt Ashton of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. “Collaborating with these organizations allows us to promote the dual objective of conservation and water quality benefits that mussel restoration can provide.”

The Anacostia Watershed Society also has an active mussel restoration program that received a grant from Washington, D.C. However, these types of efforts need greater support.

In order to protect the health of rivers and streams, Bay states need to provide dedicated funding to survey, protect and restore mussel populations across the Chesapeake Bay watershed. A mussel restoration plan for the Chesapeake Bay watershed is an important next step.

At the webinar, Tukey and McGee will detail ways homeowners can plant native grasses, clovers and other types of ground cover to create a lush lawn composed of diverse plant species. Doing so will increase soil health, which brings back a complex ecosystem of microorganisms and enables the soil to store more water.

At the webinar, Tukey and McGee will detail ways homeowners can plant native grasses, clovers and other types of ground cover to create a lush lawn composed of diverse plant species. Doing so will increase soil health, which brings back a complex ecosystem of microorganisms and enables the soil to store more water.