Marc Chagall was in love. Chagall met Bella Rosenfield in Vitebsk in 1910. For him their first meeting was all it took: “Her silence is mine, her eyes mine. It is as if she knows everything about my childhood, my present, my future, as if she can see right through me: as if she has always watched over me, somewhere next to me, though I saw her for the very first time. I knew this is she, my wife. Her pale coloring, her eyes. How big and round and black they are. They are my eyes, my soul.” Bella’s response also was love at first sight.

Chagall returned from Paris to Vitebsk in 1914 to attend his sister’s wedding and to marry Bella, and then they would return to Paris. However, World War I began, and the Russian border was closed. Chagall painted “The Birthday” (1915) (32’’ x39’’) (MoMA) a few weeks before their wedding. His ecstasy is depicted as he flies into the air to kiss Bella. He is light as a feather. Bella reciprocates, her feet lift off the floor. Chagall chose the pure complementary colors of green and red to accentuate the couple. He often depicted Bella in a black dress with a white collar and, as he described her, with black hair and black eyes. Chagall brought Bella a bouquet of flowers, another item he often included in his paintings.

The composition of this painting was carefully crafted. A rectangular blue-gray cloth with a small black pattern covers a rectangular red and orange table with round spooled legs. A round cake, a glass, a round dish of red berries, and a small purse are placed on the table. A round black stool sits on the floor. Above the table, a window with a white shade echoes the white lace collar on Bella’s dress. Outside is a Russian street. At the right side of the painting a low couch is covered with a cloth that repeats the red and orange of the table. On the floor, a small green and yellow pillow with square patches echoes the green and yellow of Bella’s bouquet. On the wall above the couch a rectangular tapestry with a paisley pattern repeats the colors used in the painting, including the bouquet of flowers. A square black clock with a round face hangs above. A blue-gray patterned cloth hangs under a window. The shapes and colors are repeated across the composition. However, none overpower Bella and Chagall as they float in air.

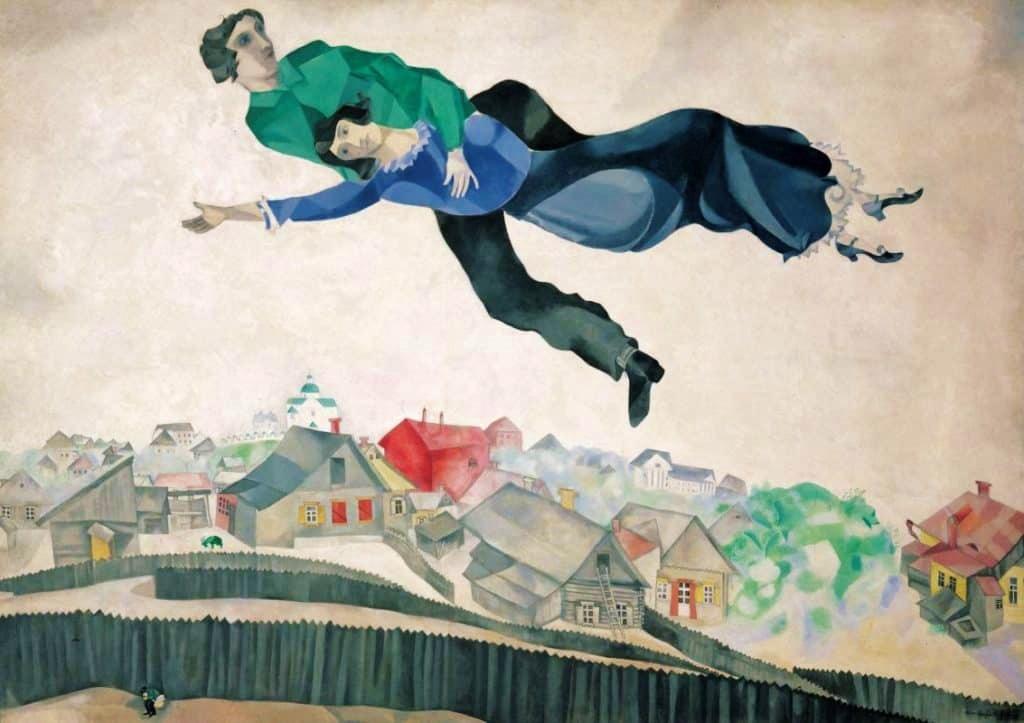

Unable to leave Russia, Chagall continued to paint his beloved Vitebsk and the nearby villages: “I painted everything I saw. I was satisfied with a hedge, a signpost, a flood, a chair.” By 1915, he began to exhibit his work in Moscow, and several rich collectors purchased his art. For a time after the October Revolution (Communist take-over) of 1917, avant-garde artists were in the favor of the Communist government, since their work had nothing to do with classical art favored by the Czar. “Over the Town” (Lionza, near Vitebsk) (1918) (17.7’’ x22”) (Tretyakov, Moscow) depicts Chagall and Bella flying over Lionza. Chagall later wrote, “She has flown over my pictures for many years, guiding my art.” He described the experience as “flying with luck…You run to the screen, shaking under your hand, immersion brush. LASHES red, blue, white, black. You (Bella) draw me into a whirl of colors. And suddenly you take off the floor and pull me with you.”

Chagall was made a commissioner for the arts in Vitebsk. Among other accomplishments he founded the Vitebsk College of Art in 1923. However, feuds with the art faculty led him to move to Moscow. There he painted murals for the Kamerny Theater and produced sets and costumes for the plays of Jewish writer Sholem Aleichem (1859-1916). Chagall and Bella joined the many Russian avant-garde artists who moved to France as his art fell out of favor and conditions in Russia became more restrictive. They left Russian in 1923.

They lived in France until 1941. Chagall was courted by the Surrealist artists who based their art on Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), in which he discussed dreams and the unconscious mind. Chagall rejected their ideas stating, “If I create from the heart, nearly everything works; if from the head, almost nothing.”

Chagall met Ambrose Vollard in 1923. Vollard commissioned a series of etchings of Nikolay Gogol’s novel Dead Souls. Chagall finished 107 full plate prints in 1931. Vollard then commissioned a series of prints based on the Old Testament. Chagall completed the set of 66 plates in 1939.

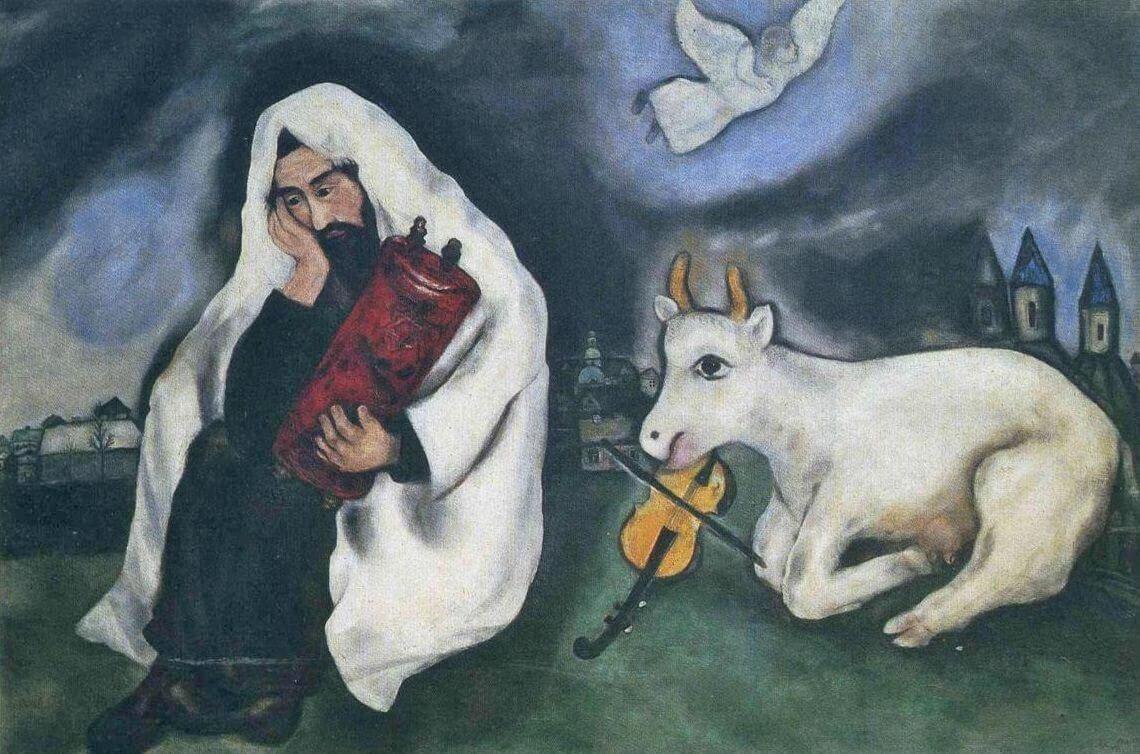

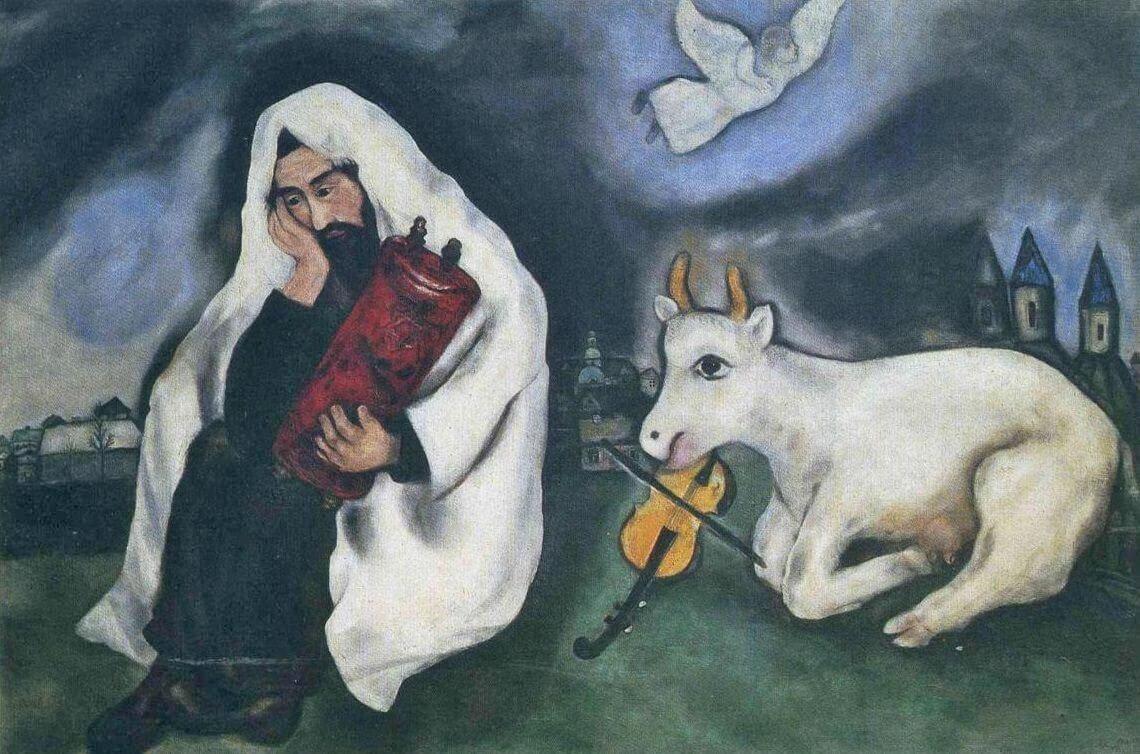

As anti-Semitism grew in Europe, and Hitler and the Nazi party came to power in 1933, Chagall witnessed a friend being assaulted on the street in Warsaw because he was Jewish. Chagall’s “Solitude” (1933) (40’’ x62.5’’) (Tel Aviv) portrays his strong fears. A solitary Jew, cloaked in a kittel (white prayer shawl), sits on the ground. His face shows despair. Chagall titled the painting “Solitude” to signify that Jews were in a lonely, uninhabited space. Solitude seems coupled with despair. The Jew is outside the town, rejected by society. He holds a torah, a hand written scroll containing the word of God to the Jews.

An upside-down fiddle is placed next to the Jew. The fiddle is one of the items Chagall frequently used as a reference to his childhood and Jewish traditions. Music was basic to Jewish life, and the fiddle provided the music that accompanied songs of the Jews. It reminded them of the failed revolution of 1905, led by the Jewish fiddler Sormus.

A kneeling goat is the third prominent figure in the composition. Its presence represents the Old Testament sacrifice by Joseph as the replacement for his son Isaac. A goat with a red ribbon tied around its neck was part of the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), when Jews ask for forgiveness of their sins. The goat was released to wander, carrying the sins of the people with it (scapegoat). The last symbol is the white angel that flies through the stormy sky. Angels, heavenly messengers, were as common in Jewish history as they are in Chagall’s paintings. Chagall’s paintings at that time were intended to awaken society to the displacement and persecution of Jews.

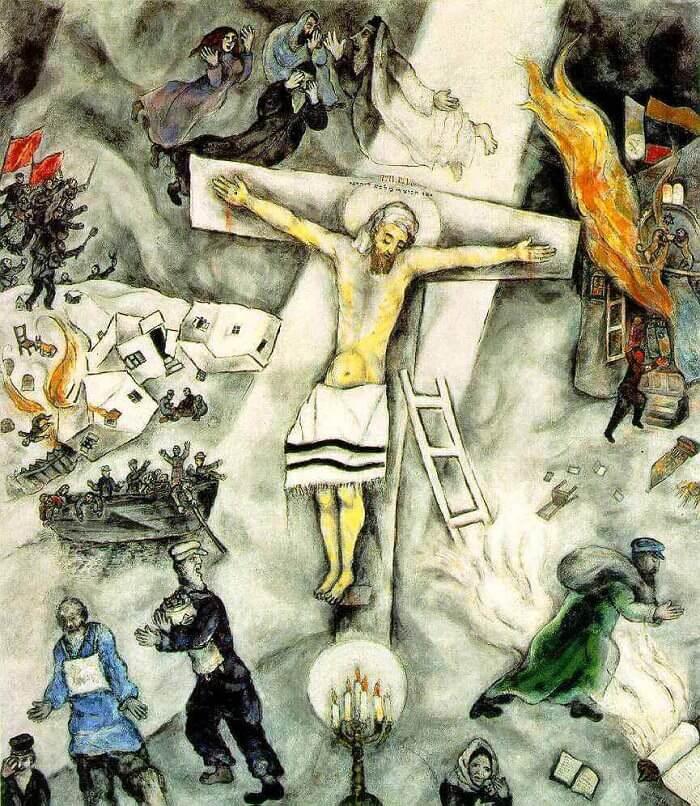

On July 19, 1937, Hitler opened the exhibition of “degenerate art.” Twenty thousand works were confiscated from German museums by Joseph Goebbels. Fifty-seven Chagall paintings were confiscated. Several were included in the exhibition. “White Crucifixion” (1938) (61’’x55’’) (Chicago Art Institute) contained the images of Jesus, the Jewish martyr.

To Chagall, Jesus was a Jew when he was crucified, and his persecution was the persecution of Jews. Jesus wears a black and white prayer shawl (tallit) and a head cloth. At the foot of the cross is a menorah with six candles. According to the Torah, the menorah made for the original Temple of Jerusalem had six candles, representing the six days of creation. A seventh candle was included to represent the Sabbath, the day of rest. However, Chagall’s menorah has only six candles; there is no day of rest.

Jews flee in all directions from the site of the crucifixion. At the lower left three men flee: one bearded, one labeled Jew, and one carrying a Torah scroll. Above them is a boat loaded with refugees fleeing from their burning town. A troop of soldiers carrying a red Nazi flag rush into the scene. Above the cross three Biblical patriarchs and a matriarch wail and pray.At the lower right, a mother cradles her child, an unrolled Torah is left on the ground, and a green clothed man flees with his belongings. Above them a synagogue burns, its contents an Ark of the Covenant (to hold the Torah), and other furnishings are tossed on the ground. The door of the synagogue remains standing. Two rampant lions of David, a star of David, and the image of the Ten Commandments can be seen. Nazi flags fly in the upper right corner.

World War II began when Germany invaded Poland in 1939. Belgium and Poland were invaded in 1940. Chagall moved from Paris to Gordes in the south of France in 1940. However, the Vichy government under Marshall Petain, cooperated with the Nazis in oppressing the Jews. In 1941, the Vichy government stripped Chagall of his citizenship and arrested him. Along with 2000 others, the Chagalls were rescued by Varian Fry of the American Aid Committee. At the invitation of Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, the Chagalls came to New York.

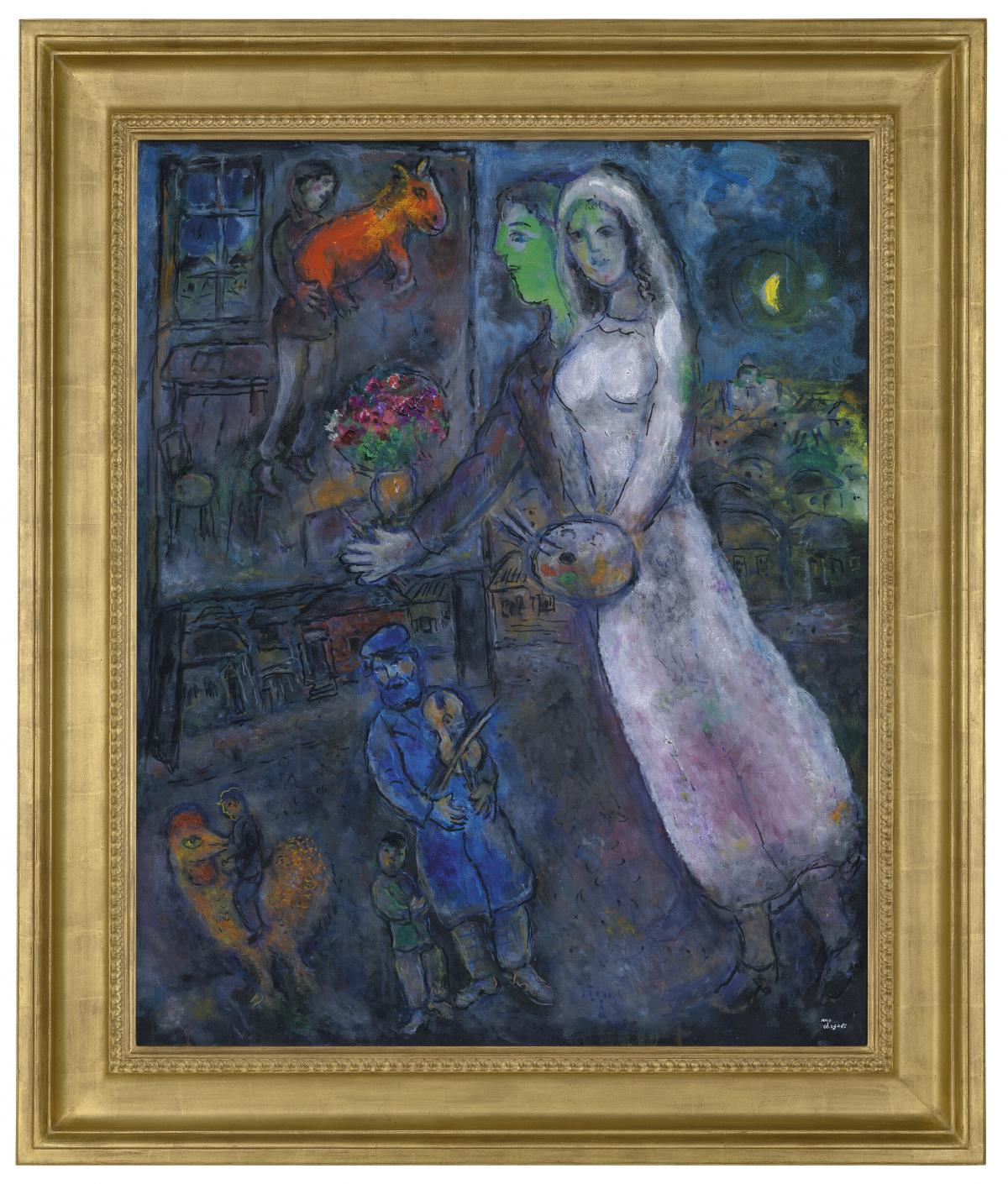

Chagall arrived in New York City one day after Germany invaded Russia. Later, he learned Vitebsk was destroyed. When Paris was liberated in 1944, the Chagalls prepared to return to Paris. However, Bella died of a viral infection. Chagall did not paint for a year: “Everything went black before my eyes. I am lost.” Although Chagall would marry again, and have a son, Bella was forever his muse. “The Painter, the Bride and Groom” (1970-74) (39.5’’ x 32’’) features Chagall and his bride floating above the ground. A blue fiddler plays for them, and a small boy, his son David, stands beside the fiddler. The painting behind them depicts a room with the painter holding a little donkey. Chagall’s pet name for his daughter Ida was Little Donkey. A vase of colorful flowers sits on the table. The room has a window, a motif Chagall often used to represent freedom. At the lower left corner, a rooster, one of Chagall’s favorite animals, represents fertility. Chagall may be riding the rooster. The painting was sold a Christies in London for $1,670,256.80.

Chagall returned to Paris in 1948. He lived in France for the rest of his life, but his career as an artist was only half over. Next week’s article will feature the last half of Chagall’s life.

“The title ‘A Russian Painter’ means more to me than any international fame…In my pictures there is not one centimeter free from nostalgia for my native land.” (Chagall)

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.