King Ludwig I of Bavaria (Wittelsbach) was born in the Nymphenburg Palace in 1845. He died in 1886 under mysterious circumstances. He and his brother Otto lived in Hohenschwangau (High Swan Castle), built by his father King Maximilian II of Bavaria. The boys were brought up to learn their duty as intended leaders of Bavaria. Ludwig took his education very seriously. However, his mother Marie of Prussian noticed another side to her son, and she wrote, “Ludwig enjoyed dressing up…took pleasure in play acting, loved pictures and the like…and liked…making presents of his property, money and other possessions.” Crown Prince Ludwig also was fascinated particularly by the music and drama of Richard Wagner’s operas.

Ludwig became King of Bavaria in 1864 at age 18. In 1873 he reflected upon his reign: “I became king much too early. I had not learned enough. I had made such a good beginning…with the learning of state laws. Suddenly I was snatched away from my books and set on the throne. Well, I am still trying to learn….” His reign lasted only two years. Bavaria was conquered by Prussia, and Ludwig became a vassal of his Prussian uncle. Ludwig had no real power.

Ludwig traveled to Paris in 1867, and he visited Versailles. He understood the importance of the castle as a symbol of power. Ludwig was related to the French Bourbons, and he felt a strong relationship with them and the kingly power they possessed. He believed he was head of state by the grace of God, but that role was taken from him.

Two years after his displacement, Ludwig commissioned the building of Neuschwanstein (1868) on the mountain above Hohenschwangau. It was to be a show of power and fantasy. Set designer Christian Jank drew the castle based on Ludwig’s specific visions of Versailles and the castles of the Christian Knights of the Middle Ages in Wagner’s operas. The architecture is Gothic, Romanesque, and Byzantine. The architect and set designer Eduard Riedel oversaw construction according to Jank’s painting. Construction began in the summer of 1868, and the corner stone was laid in 1873. The foundation was cement and the walls were brick, but the exterior was clad with light colored limestone. The original design included 200 rooms, but no more than fourteen were finished. Neuschwanstein provided the setting for Ludwig’s private fantasy of living as a Swan Knight or a King. Ludwig was said to sleep during the day and rise at night.

The Throne Room was designed after a Byzantine Basilica. Ludwig was a Catholic. The gold mosaics in the apse depict Christ surrounded by angels. The Madonna kneels at Christ’s right and John the Baptist kneels at the left. Below are six holy kings. Marble steps lead to a platform where the throne would be placed. It was on order when Ludwig died; the order was cancelled. The mosaic floor is designed in a circle to represent the Earth and depicts many of God’s creatures. Along the sides are Imperial Red Porphyry columns. First discovered in Egypt, Imperial Red Porphyry is rare and a symbol of wealth and power.

On the walls are depictions of the twelve apostles and the deeds of kings and saints. The room is two stories high, making space for the chandelier (13’ tall). In the middle of the arched ceiling is a large dome, painted blue to represent the sky and covered with gold stars. Ludwig would rule under heaven and over the earth. On the wall opposite the throne is a large painting of St George slaying the dragon.

Wagner’s opera Parsifal (1877) is about one of King Arthur’s knights who searches for the Holy Grail. Parsifal is young and innocent, but along the way he learns a great deal about the world and about compassion. Wagner included many of Ludwig’s problems in the story and referred to Ludwig as Parsifal. The Throne Room was renamed the Hall of the Holy Grail.

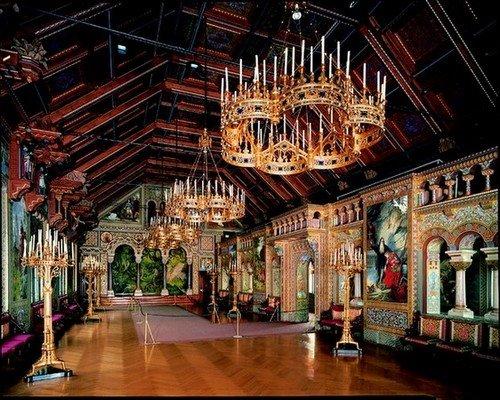

The name Singer’s Hall is a reference to Wagner’s opera Tannhauser, the title character a minstrel and poet, and the Warburg Song Contest. At 2906 square feet, the Singer’s Hall is the largest room in the castle. It was intended to be a ballroom and a theater. The walls are painted with scenes from Lohengrin and Parsifal. Enormous gold chandeliers hang from the Gothic wood-beamed ceiling.

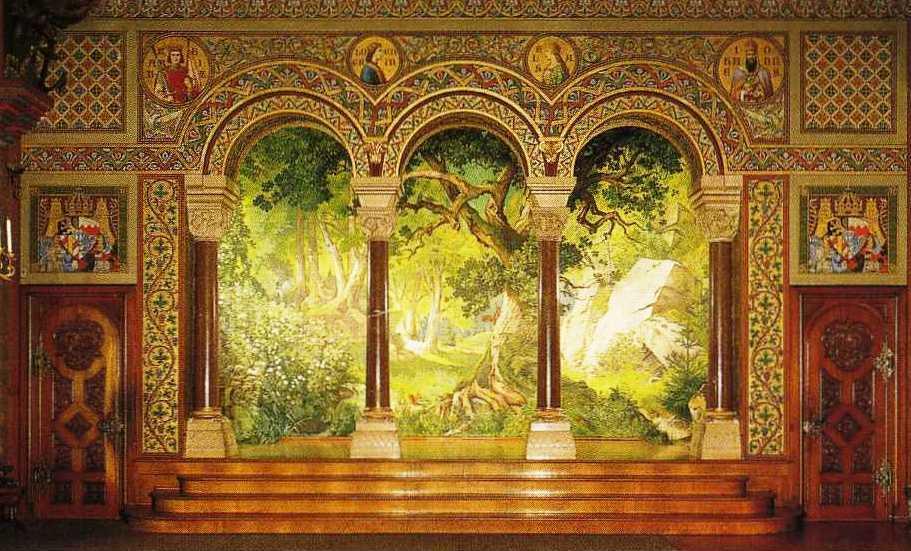

The stage of Singer’s Hall contains a painted backdrop of Klingsor’s Forest. In Parsifal, Klingsor is an evil magician who was rejected as a Knight of the Holy Grail. The forest is the setting for his attempt to kill Parsifal, but a miracle occurs, and Parsifal is successful in his quest for the Holy Grail. There were no performances in the Singer’s Hall until 1933, on the 50th anniversary of Wagner’s death.

Ludwig’s obsession with Wagner and his operas was matched by his obsession with modern conveniences. Neuschwanstein had running water throughout, hot and cold water in the baths and kitchen, flush toilets, and forced-air central heating. An electrical bell system was installed for calling servants, and meals were brought by lift to the dining room from the kitchen three floors below. The kitchen has a large stove, large and small spits, a built-in roasting oven, plate warmer, baking oven, and fish tank. Ludwig had a telephone installed, although few phone lines were available. He could call only the nearby village of Fussen.

Beneath the salon and study on the third floor, a grotto was built to represent Venusberg, Wagner’s interpretation of the ancient “Tannhauser” poem. Tannhauser was a mortal man who succumbed to the seductress Venus in Wagner’s opera. An erotic seduction scene is painted in Ludwig’s private apartments and on the rear wall of the cave. Ludwig commissioned August Dirigl, a stage designer, to construct the cave with stalactites and a waterfall.

Ludwig saw Lohengrin when he was 15, and Wagner and his operas became a lifelong obsession. After he became King, he summoned Wagner to Munich in 1864, and he supported Wagner from then on. Ludwig was moved by their first meeting: “Today I was brought to him. He is unfortunately so beautiful and wise, soulful and lordly, that I fear his life must fade away like a divine dream in this base world…You cannot imagine the magic of his regard; if he remains alive it will be a great miracle!” Ludwig made a promise to Wagner: “I’m going to build a fantasy castle dedicated to your works and we should go live there together forever.” He described the location to Wagner “as one of the most beautiful to be found, holy and unapproachable, a worthy temple for the divine friend who has brought salvation and true blessing to the world. It will also remind you of Tannhäuser and Lohengrin.”

Ludwig’s sponsorship made Munich the music capital of Europe. The premiers of Tristan und Isolde (1865), Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1868), Das Rheingold (1869) and Die Walküre (1870) were sponsored by Ludwig. Wagner was forced to leave Munich in 1865 as a result of his anti-Semitism. Ludwig did not agree with Wagner on this point but continued to support his music. Wagner conducted a private performance for Ludwig of the prelude to Parsifal at the Court Theatre in Munich in 1882. Ludwig’s plans for an opera festival to be held yearly were realized when Der Ring des Nibelungen was performed as the inauguration opera of the Bayreuth Festival in 1876.

Ludwig spared no expense on the several castles he built. Foreign banks threatened to seize his property beginning in 1885, as a result of non-repayment of loans. Ludwig lived at Neuschwanstein for six months off and on, and reports say he spent only 11 nights there. The government in 1886 declared that Ludwig was insane and deposed him. He was interned in Berg Palace. The following day (June 13, 1886), Ludwig drowned in Lake Starnberg under mysterious circumstance.

When Ludwig was a young boy, he said to his governess, “I want to remain an eternal mystery to myself and to others.”

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.