Jean Honore Fragonard (1732-1806) became one of the most popular painters of the French Rococo style. The courts of King Louis XV (1715-1774) and Louis XVI (1754-1793) were known for their luxury and excess. Although it was the age of Enlightenment, with Voltaire wanting religious toleration and Diderot publishing the first encyclopedia, Fragonard’s patrons wanted scenes of festivals, mythological lovers, and entertainments, often with sensual implications.

Fragonard’s patrons often requested series of paintings in groups of four or five. The National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.) contains four of these paintings. “Blind Man’s Bluff” (1775-76) (85’’ x 73’’) depicts a large garden of a French estate. Under a blue sky with fluffy white clouds, two fountains, formal flower beds, a variety of tall trees, marble colonnades, and a well-groomed lawn provide a romantic and breath-taking setting. At the right, members of the party enjoy a luncheon buffet while they watch a game of blind man’s bluff. Closer in, a couple enjoys sitting on the grass as they too look on.

The marble fountain at the left spurts high into the air. The female figures that form the base of the fountain may represent the Vestal Virgins, Roman maidens who served the goddess of the Hearth, Vesta. Their job was to see that the sacred fire of the hearth never went out. To be a Vestal Virgin, a young girl was required to take a vow of chastity. Another statue of a woman can be seen on a hilltop at the right. Too small to identify, it is likely a statue of the goddess Vesta, or possibly Athena, who frequently is depicted wearing a helmet because she is both the goddess of wisdom and war.

The main attraction is the blind-folded young woman in a white gown, who turns awkwardly around trying to find one of her friends. Others in the party dodge to stay out of her reach. The game is fun, but its depiction is intended to suggest the difficulty of finding a suitable partner. Or, given the presence of the Vestal Virgins, perhaps the message would be it is better to remain unmarried. In the distance others enjoy this pleasant park.

“The Swing” (1775-76) (85” x 73”) is the companion to “Blind Man’s Bluff.” The viewer can see the matching trellis of pink and red flowers at the lower left and right corners of the two paintings when they are hung side by side. The foliage of the trees also presents a continuous view across the paintings. A young woman, dressed in pink and gold, sits on the swing. She raises her left hand to greet her friends. The swing is pulled with a rope by a gentleman who stands between the two fountains, the water flowing from the mouths of the lions. At the left corner, a gentleman in green and a woman in red play with their child in the lion fountain. Her friends watch from the lawn and talk with one another.

At the right corner of the painting, a woman in red and her companion sit on a marble platform. She is looking through a telescope. Too close to be using the telescope to look at her friend, she appears to look off into the distance. What is she looking at? Or more interesting, what is she looking for?

Is this Fragonard work just another lovely scene of people having fun, or could there be another interpretation? Paired with the blind-folded woman seeking a mate, the back- and-forth movement of the swing and the pulling on the rope suggest the culmination of the act of love. Although these suggestions were slight, other of Fragonard’s paintings, for instance his “Swing” of 1766, leave no doubt about the intention of the artist with regard to the desires of his patrons.

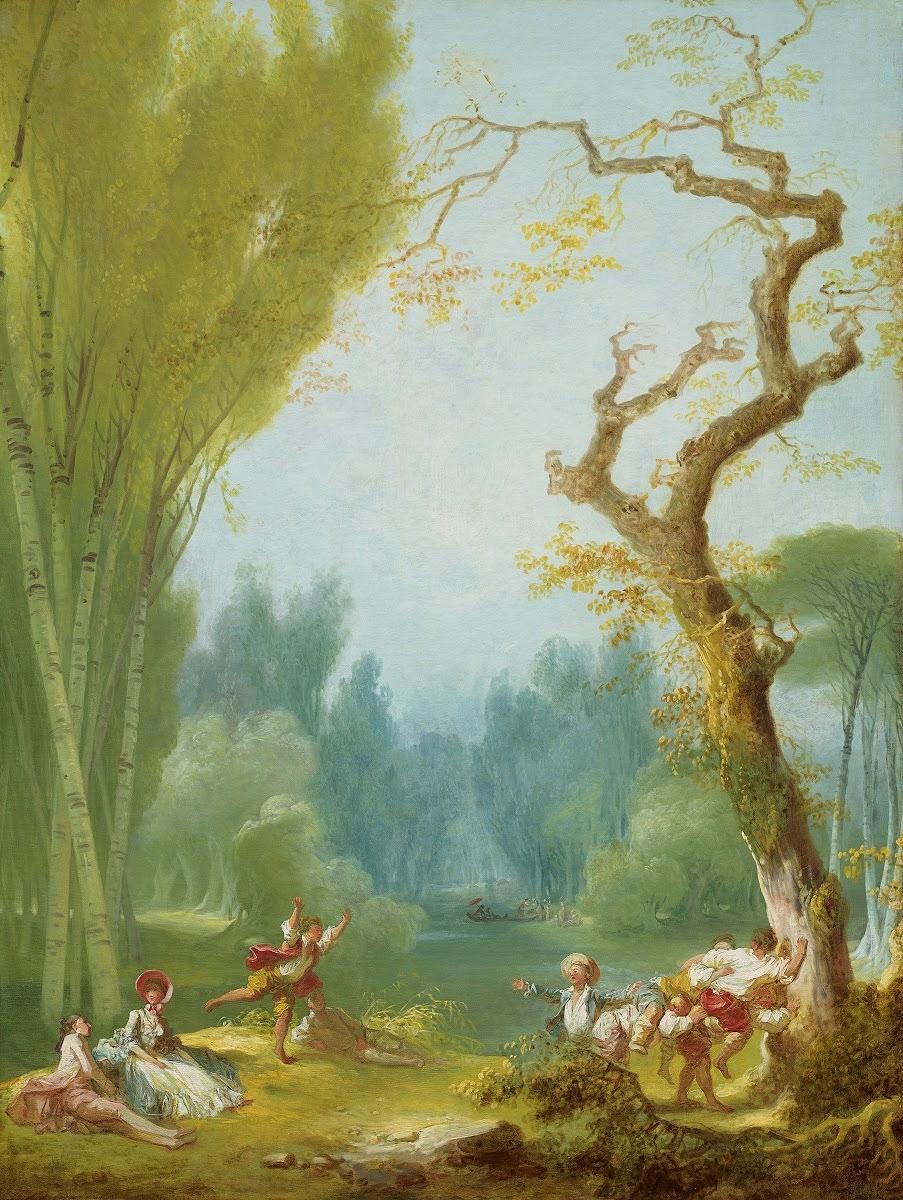

“A Game of Horse and Rider” (1775-80) (45.5” x34.5”) again depicts a scene set in a large garden. However, this garden is natural, not formal, as is the subject matter. The informal garden does not have not well-designed flower beds, or carefully organized marble walls. The trunks of the tall birches at the left side crisscross each other, reaching high into the sky, with their, leaves fanning out. At the right side an old gnarled tree, missing most of its leaves, is silhouetted against the sky. There are no paths, and the grass meets a winding stream, where in the distance a gondola pulls up to the shore to let off passengers who have come to enjoy the day.

The figures in the foreground also provide contrast. The adults at the left of the scene lounge quietly on the grass, engaged in conversation. Beyond them a young boy runs, feet flying and arms raised in anticipation of jumping into the game. The rowdy game of horse and rider takes place under to the old tree.

The game of horse and rider is made up of two teams. The multi legged horse team braces itself against the tree. The riders race in and jump onto the horse. It is then the job of the horse to try to shake off all of the riders. This accomplished, the teams trade places. It is a rough and tumble game for boys. Meanwhile, the young man and woman may be discussing a later “tussle” of their own.

“A Game of Hot Cockles” (1775-80) (45.5” x 34.5”) is the companion piece to “A Game of Horse and Rider.” There is evidence that these paintings were cut down to make them shorter. However, the dates and subject matter suggest they were a part of the same series, or of a very similar series by Fragonard. He created many of these painted series. Both paintings depict a couple lounging on the grass and engaging in private conversation. The gardens contrast the natural with the formal, and have paths at the center that lead into the distance. The “Hot Cockles” garden is formal, with designed beds, steps leading to a path, and sculptures. A young couple sits on a stone bench at the left.

A game of hot cockles is being played by a lively group of young people at the right side of the painting. The game of hot cockles, has nothing to do with cockles and muscles, but was a sensuous treat. The “penitent,” the man dressed in gold, kneels before a young woman, placing his head on her lap. How often would this have occurred? His hand placed on his back, he endures other players taking turns slapping his hand, or his bum. It is his job to decide who has slapped him. In this instance, he appears to point at either the lady in blue or the other woman who huddles with her. Of course, the “penitent” can misidentify who has slapped him in order to continue to bury his face in the woman’s lap.

Two sculptures are placed in the garden. The figure of a woman at the left is most likely a goddess, but not so identified. At the right, on top of the pedestal is the well-known sculpture titled “Menacing Cupid” by Etienne Maurice Falconet. Cupid holds his finger to his lips, and he watches the naughty game.

Fragonard’s travels to Italy, including several visits to its beautiful parks, gardens, and fountains, left an indelible mark on his imagination. Although the four paintings in the National Gallery were not painted in Italy, they reflect Fragonard’s enthusiasm for his subject. He painted with a fluid brush stroke well suited to the charm of his figures and their settings. He is described by art historians as a virtuoso.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.