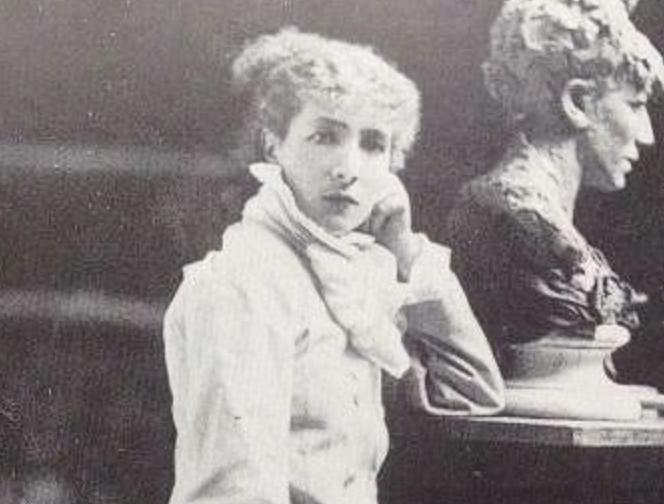

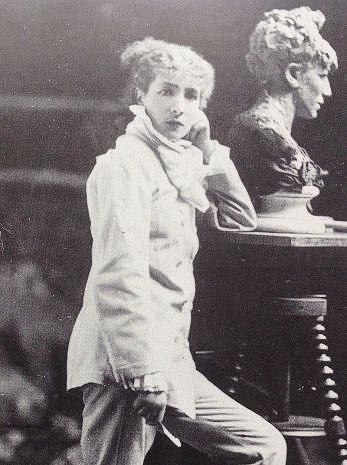

Henrietta-Rasine Bernard (1844-1923) is better known by her stage name, Sarah Bernhardt. Her 60-year career on stage went well beyond acting. She designed her own costumes, wrote plays, essays and novels, designed dresses, supervised sets and costumes for her productions, became the director of a theatre, was a film star, and beyond all that, she painted and was a well-know sculptor. She began art lessons in 1863 at the Conservatory of Paris while she worked at the Comedie-Francaise. She studied with French sculptors Mathieu-Meusnier and Jules Franeschi, and she took painting lessons from Alfred Stevens. Bernhardt opened her own studio on Montmarte in 1873.

Bernhardt began with portrait sculptures and frequently depicted women from her stage roles through her sculptures. Her life as an actress and artist was criticized. During the Franco-Prussian War (1871), she was accused of being both Jewish and German. Her response: “Jewish most certainly, but German, no. If I have a foreign accent—which I much regret—it is cosmopolitan, but not Teutonic. I am a daughter of the great Jewish race, and my somewhat uncultivated language is the outcome of our enforced wanderings.” Sculptors such as Rodin criticized her for pursuing an inappropriate activity for a woman. Wearing the white male trouser suit was against the female dress code. Emile Zola defended her. He wrote, “How droll! Not content with finding her thin, or declaring her mad, they want to regulate her daily activities, … Let a law be passed immediately to prevent the accumulation of talent!”

During her career as a sculptor, Bernhardt participated in the Paris Salon Exhibitions from 1874 until 1886. Her work was exhibited in London, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago. There are 50 documented works. “Hermione” (1875) (18.5’’) is both signed and dated. Hermione was the only child of Helen of Troy and her husband King Menelaus, and she was nine years old when Paris kidnapped Helen. Bernhardt starred in Racine’s play Andromeda in 1873, and she began the bust shortly thereafter. Hermione commits suicide and her lover/husband Orestes blames himself. Mad with grief, Orestes has a vision of Hermione accompanied by the Erinyes or Furies, female demons from the underworld. With snakes for hair, black bodies, and bat wings, they hound evil doers until they die. In a line from the play, Orestes clearly describes Bernhardt’s sculpture: “For whom are these snakes which hiss on your head?” Bat wings and snakes emerge from her hair. Hermione’s eyes and facial expression relay Bernhardt’s intent.

“After the Storm” (1876) (30’’x24’’x23’’) (National Museum of Women in the Arts) was inspired by an incident witnessed by Bernhardt. A Breton woman mourns her grandson, who during a storm was caught up in a fishing net and drowned. Barnhardt’s talent is well demonstrated in this work. The viewer’s empathy is immediately aroused by the composition and the characters. Perhaps the viewer may have a visual memory of Michelangelo’s famous “Pieta,” and it is likely Bernhardt did as well. Forming a powerful triangular composition, the old woman’s body supports the body of her grandson. The folds of her garments masterfully sweep to form a triangle over her shoulder and leads diagonally across her body to that of her grandson. The heavy drapery on her right knee forms another triangle that supports his limp body. A bit of the net shows beneath his legs, and a few waves roll up against his grandmother’s skirt. Bernhardt offers a sign of hope; the young boy’s right arm swings upward, and his hand grabs a fold of her skirt.

Bernhardt’s attention to detail and her emotional attachment to the subject can be witnessed in the detail of the woman’s face. Age and emotion are well rendered. Her wrinkled neck and the smoothness of her hair denote her age. Her facial expression appears appropriately anxious, enhanced by her wrinkled brow.

Bernhardt’s chosen roles tended to be powerful and tragic; Ophelia, Medea, Camille and Hamlet are good examples. She was also known to sleep frequently in a coffin. Bernhardt and Victor Hugo were friends and mutual admirers. Bernhardt played several of Hugo’s heroines. “The Fool and Death” (1877) (33”x28.5”x31’’) refers to Triboulet, the main character in Hugo’s the Le Roi s’amuse (The King is Having Fun). Triboulet is the court jester to the King of France, Francis I. Triboulet does all he can to prevent the King from seducing his beautiful daughter. Failing, he decides to kill the King, but the plan goes horribly wrong and he accidentally kills his daughter. In his jester’s costume, Triboulet sits crossed legged on a rock. Bending forward in grief, he holds a skull out to the viewer. Bernhardt has captured Triboulet’s tragedy.

“Encrier fantastique” (Magical inkwell) (1880) (12’’x7’’x9’’) (bronze) is one of the small useful objects sculpted by Bernhardt. She played the role of Berthe de Savigny in Le Sphinx (1873), a melodrama by Octave Feuillet performed at the Comedie Francaise. In Greek mythology, the sphinx was a woman with the body of a lion, the head of a woman or a beast, the wings of an eagle, and sometimes a serpent’s tail. Bernhardt’s sphinx is a self-portrait. She has bat wings, and her griffon’s claws hold an ink well with a skull on the top edge. A feather pen would have projected from the back of the piece. Not visible in this view are the masks of tragedy and comedy that form the shoulder pads of her dress.

When she was criticized in the press in 1881, an article in Naturalisme au théâtre (Naturalism on the Stage) defended her: “How odd that not content with finding her too thin and declaring her mad, they should now want to regulate her daily activities. … Let us pass a law immediately to prevent the accumulation of talent! … This is how things go in France: we do not accept that any individuality should escape from the art to which we have assigned them.”

“The Divine Sarah” successfully pursued her various careers until her death on March 26, 1923. Mark Twain said, “There are five kinds of actresses: bad actresses, fair actresses, good actresses, great actresses—and then there is Sarah Bernhardt.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Linda hall says

Wonderful, i so much enjoy this colomn every week. Please don’t stop. Linda hall