I know, I know, Daylight Saving Time, humankind’s eternal quest to screw with circadian time to gain an extra hour to shop, play golf, and barbeque while blaming the annoyance on schoolchildren having to wait in the dark for busses to arrive.

So we woke up today with that unnerving feeling that something is off and that we might be failing some sinister societal experiment, wander haplessly into our kitchens wearing one sock, put Quaker Oats in the coffee maker while having a lucid daydream that clocks may have been set back far enough for it to be Saturday again, a delusion quickly dashed by the fact that we have to run out to change the car clocks and grow-light timers.

We do, however, have that extra hour to wonder why a time mandate isn’t a causes célèbre for militias to storm the Capital waving alarm clocks; who might be sitting alone in the wedding pew alone, wondering if dancing naked while twirling sparklers may have been a bridge too far for the bride’s family to allow the ceremony to proceed; or if the NORAD computers have safely reset.

And let’s not get into EST, Mountain, and Pacific times because it’s enough to think about Ben Franklin’s truth in jest that DST would save Paris millions of francs by using fewer candles. Be relieved that it’s not the same as1945-1966 when no federal law called for any uniform time and states and cities could set their clocks depending, I assume, on when they wanted Happy Hour.

All you need to know about the push for year-around DLT is to look into the life of Abraham Lincoln Filene of the Filene’s Department Store empire and his obsession to capture daylight for more shopping during WW1. He’d be sorely disappointed to know that eventually, 29 states would introduce legislation to quit messing with the clocks.

But, be still your heart, here’s another story about humans trying to lasso time-space.

Some years ago I was commissioned to write a review of a resort on the Bay coast of the western shore. It was all cheers until a tropical storm hammered the coast and wind-whipped the outdoor proscenium where a wedding was to be held, forcing the ceremony inside. My “comped” room was three floors above an indoor pool venting chlorine directly into the third floor, no doubt an effort to kill the reviewer they feared would write something negative about the dinner allowance he was not given.

Bonus: at 2 am banging on my door shocked me awake. Under the influence of more than chlorine, someone was pummeling my door, mistaking my room for another’s. I opened it to a tsunami of bridesmaids in remnants of lime green chiffon and sulky groomsmen barely able to hold one another up and retch at the same time.

So far, so good. The article was turning into a survival manual.

The next morning, I decided to reset the trajectory of my weekend by browsing flea markets and antique stores in my quest to find that overlooked first edition book that would alter my financial life. I found a likely shop and wandered through its aisles of empty picture frames and threadbare sofas until I came across the proprietor, an owlish-looking fellow in a bowtie sitting at his desk and writing in a ledger. We talked for a while and finally, I asked my favorite question. “In all your years, what is the oddest, strangest, most out of the ordinary thing you’ve ever acquired?”

Without pausing, he said. “It would be the 1,000 pound 13-month concrete calendar I’ve had for a while.” I felt a slight synaptic short-circuit as I tried to imagine that.

OK, fine, I thought, this would dovetail nicely with chlorine poisoning, corridors strewn with unconscious bridesmaids, and hurricanes.

Solaris: The prototype of the 28 day 13-month calendar used to promote the passage of legislation for a new US calendar system in the 1920s.

Turns out the fellow had been a Senate Parliamentarian for several decades—somewhere between Jimmy Carter and George H. W. Bush— and that he had acquired the concrete calendar through means undisclosed to me, and that it was a prototype used to illustrate a plan presented as the Liberty Calendar to the 1922 House Judiciary Committee, a plan to change the world as we knew it, or at least how me measured days and months. Those darn Progressives.

“We have replaced the old-time hand sickle with the modern self-binder, we have replaced the oxcart with the automobile, we have replaced the wooden plow with the farm tractor, and it will be a sad reflection on the intelligence of this age of telephones, wireless telegraphy, and airplanes if we shall not be able to substitute for this cumbersome calendar of the ancients a modern and convenient,” Minnesota Representative Thomas D. Schall told the committee.

The antique dealer did in fact, have the calendar in his backyard and offered me a shadowy and vague black and white photo of it while telling me the story behind it.

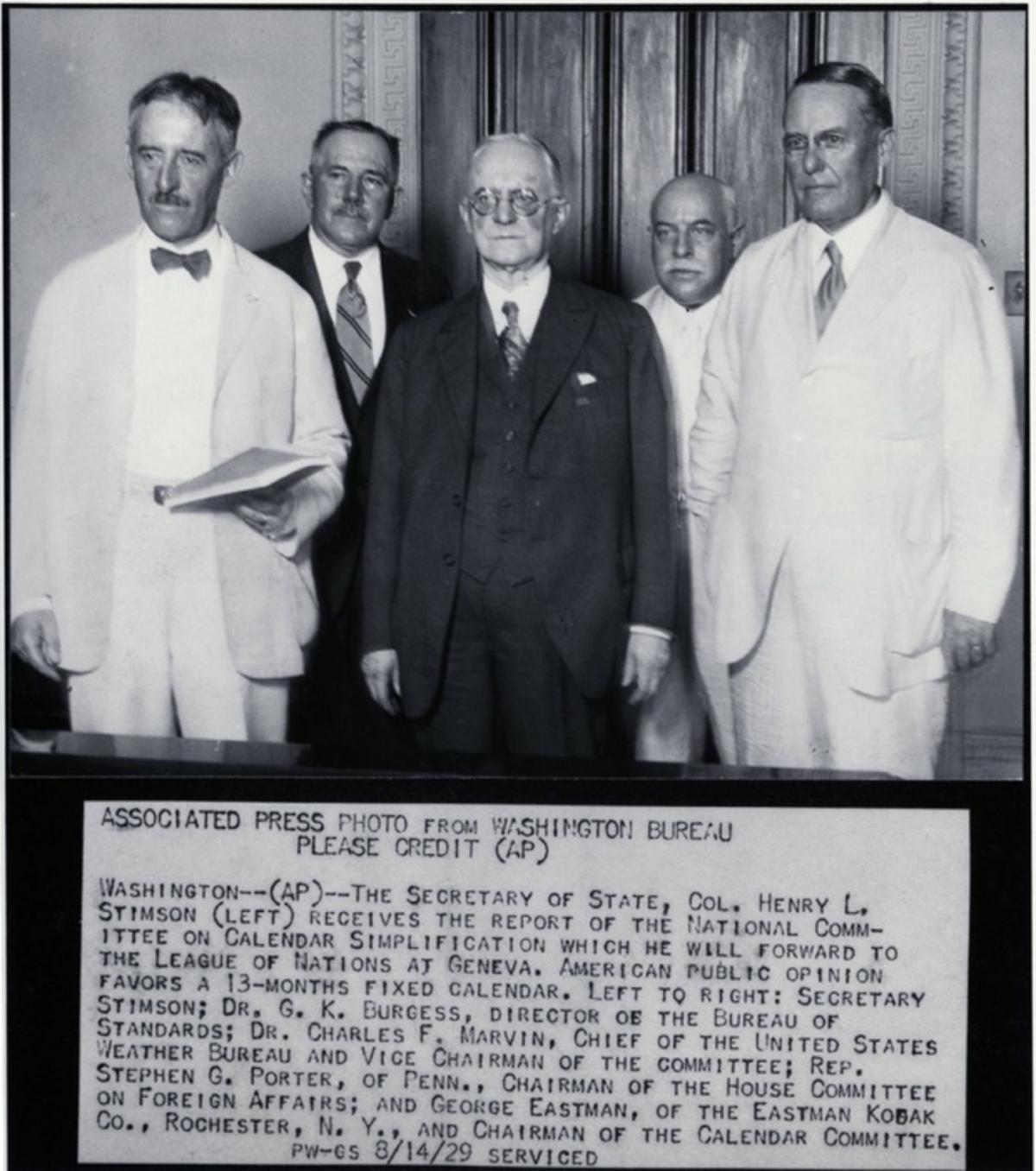

George Eastman with Secretary of State Henry Stimson. 1929.

Backed by George Eastman of Kodak fame and other captains of industry, the 13-month calendar sought adoption in the US and League of Nations. The plan was pretty much DOA, however, when people realized the 4th of July would fall on the 17th of “Sol,” a month added between June and July. Eastman saw the 13-month calendar as a perfect business model for figuring profit, cost, and streamlining bookkeeping. The rest of the world, not so much, especially when they got to the part about four Friday the 13ths a month.

The so-called International Fixed Calendar, or Solar Calendar, had thirteen uniform months with 28 days and had roots in the mid-18th century and probably Babylonia, where math was invented. But leave it to an Eastern Shore colonist named Hugh Jones to introduce an American version of the calendar, each month named after a saint; not quite as snappy as the French calendar of 1849 concocted by French philosopher Auguste Comte who proposed the Positivist Calendar, naming the months: Moses, Homer, Aristotle, Caesar, and so on. “See you in Homer for the family reunion.”

Still, all of these had that pesky leap year thing tacked on wherever they could to pretend they had harnessed the chaos of the natural world. None of the proposed calendars, except in George Eastman’s business until 1989, were ever employed, and the scrapped the idea in 1937 as the International Fixed Calendar League offices finally closed with hardly a whimper, leaving the use of the 13-month system found in use only by Ethiopia.

So, feel lucky. Just set your clocks for now until we all surrender to Universal Time based on the speed of the earth’s rotation.

Katherine E LaMotte says

Thoughtful, illuminating and fun piece – thanks, Jim!

Carol Casey says

Not holding my breath for that, setting time to the speed of the Earth’s rotation, to come to pass.

Jack Fancher, retired NOAA oceanographer says

Universal Time is NOT based on speed of earth’s rotation. It is based on the fact that longitude divides the earth into 360 degrees at the equator, converging at the poles. UT was designated as zero degrees Meridian and 0 hour at Greenwich, England by an international convention in the late 1800s Nearly all of the 26 participating countries, except France, who wanted Zero Meridian through Paris. The other objector was Brazil’s leader (king?) who was a member of the French Academy of Science. 360 degrees divided by 24 hours = 15 degrees per hour, the standard on which time zones were originally set..

Jack says

Correction to my previous email. I am incorrect using “NOT”. Strike it please. It is based as I said on the 360 degrees in 24 hours yields 15 degrees per hour.

Sorry, I was a little full of myself telling how time zones came about.

James Dissette says

Gotcha, well it sent me back to look at any rate. Complicated! Thanks!!