Shan Goshorn (1957-2018), a member of the Eastern Band Cherokee, was born and raised in Baltimore, Maryland. During her childhood she spent summers at the Qualla Arts and Crafts Cooperative Mutual in Cherokee, North Carolina, where she photographed basket makers. She attended the Cleveland Institute of Art and received a BFA from the Atlanta College of Art in 1980. The next year, Goshorn moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma, and was hired by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board to photograph native arts exhibitions and to draw 20 Cherokee basket patterns. “By the time I got to number 16, I thought–you know what, I can do this and I can combine the process with issues of sovereignty.”

“I had been doing work that addressed women’s issues, but I wasn’t involved with Native human rights issues the way I became in the ’90s.” Inspired by the American quincentennial (500) year celebration (1992) of Columbus’s arrival in America, Goshorn began her first photographic series about native rights. She titled the series Honest Injun. “So, I took my kids to the grocery store, and I said, ‘Anything you can find with an Indian on it or an Indian name, put it in this cart.’ And I thought we’d have three to eight items. We ended up with like 40 items, and it made me realize how insidious this was even to Native people. You know, how Jeep Cherokee or the Winnebago–just so many things that we take for granted that we see and we just don’t even think about it being the name of a nation of people. That’s really what got me started thinking about using art as an activist weapon, as a tool for education and persuasion.”

Goshorn started making baskets in 2008; she wove over 200 baskets. She explained why baskets: “They’re such a familiar shape. They’re a vessel that every culture experiences. We associate it with caring, nurturing things, whether it’s babies or carrying wood or carrying crops or carrying water…’’They’re pretty, they’re colorful, they’re interesting… [people] literally lean into the work, and that’s the moment when we can have this honest dialogue, this conversation I’ve been trying to have with my work for 20 years. Instead of leaving so agitated … they actually leave feeling like they know more about American history, and they can understand why these topics are relevant now.”

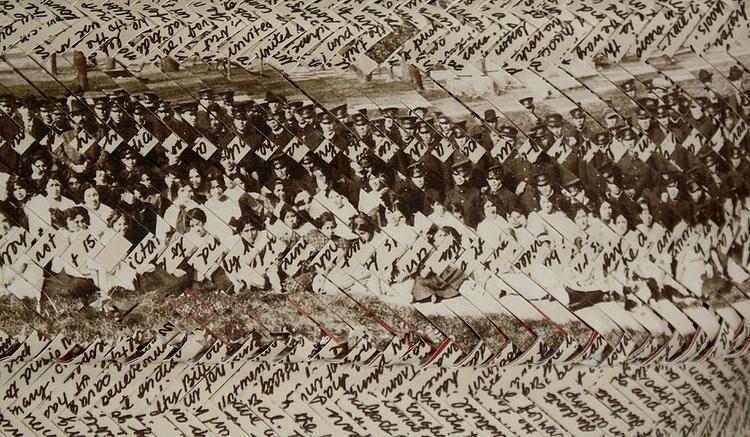

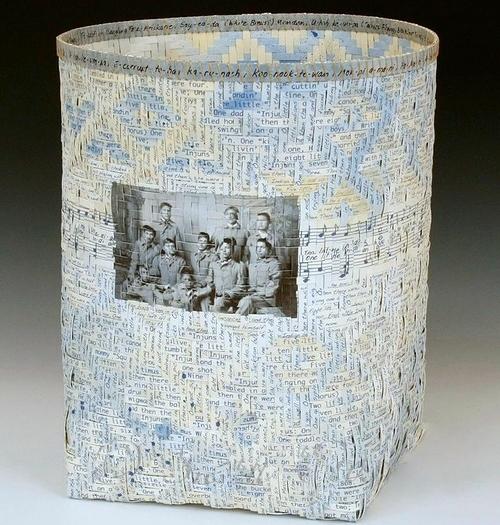

“Educational Genocide” (2011) (12’’x20”x12”) (double weave) is woven archival watercolor paper that has been printed with archival ink and then cut into splints (thin flexible strips used in making baskets). The splints for this basket are made from printed copy of the speech by Captain Richard H Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, in which he announced his intention: “Kill the Indian. Save the Man.” The image is a 1912 photograph of the student body.

“Educational Genocide” is a lidded basket woven in a double weave, the interior and exterior walls seamlessly woven together. The weaver begins at the interior bottom and weaves up the sides, weaves down the sides, and finishes at the bottom. There is no obvious beginning or end. Goshorn was only the fourteenth living member of the Eastern Band Cherokee to master the technique. The interior of the basket is red, with splints made from a list of 10,000 to 12,000 names of the children who attended Carlisle from 1879 to 1918. Among the Native children were two of Goshorn’s great grandparents.

Each of Goshorn’s baskets is a record of the life of Native Americans and the treaties or other documents that reveal their betrayal. For example, “39” (2012) (not pictured) is woven with splints made from a copy of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. It gave Andrew Jackson the power to negotiate land trades to move the Indians to the west. The Act resulted in the forced march of Indians to Oklahoma known as “The Trail of Tears.”

“Separating the Chaff” (2012) (20.5’’x 20”x 5.7’’) (double weave) is woven in the style of a basket used for sifting and winnowing grain. Goshorn’s interior splints are made with illustrations and text from a 1960s school book depicting what American students were taught about Indians when Goshorn was in school. “This basket is meant to show that Indian people need to actively decide how we want to portray ourselves; we need to actively filter through the misperceptions and untruths.”

“10 Little Indians” (2013) (11.5” x11.5” x13.5’’) is a single weave basket named for the familiar children’s song dating from the 19th Century. The image on one side is a copy of an historic photograph taken in 1878 of ten Indians (not pictured). They represent several different tribes and were photographed when they arrived at Carlisle Indian School. The opposite side contains a photographic copy of ten Indians dressed in military uniforms, the clothing they wore at Carlisle. Goshorn explains: “During my research, I felt that the ancestors were helping me because they are impatient to have their stories told. Hand-written around the rim of the basket are the tribal names of the Hampton boys, in recognition and honor of their true identities.”

The song “10 Little Indians” was written by Septimus Winner in 1868. Woven into the basket are three of the several versions of the song that included these lines: “one got executed and then there were nine,” “One got syphilis and then there were eight.” “One broke his neck and then there were six,” or “One chopped himself in half and then there were six.” “One got dead drunk and then there were three.” “One passed out drunk and then there were two.” “One shot the other and then there was one,” or ”One shot himself and then there was one. He went and hanged himself and then there were none.” Other versions replaced the word “Indians” with a reference to “African-Americans,” and the song was used in minstrel shows.

Goshorn also was a strong advocate for women. “Hearts of Our Women” (2015) (double weave) consists of one tall basket (8” x8”x 26”) woven with brown, red, and copper foil to resemble a fire with flames rising. It is surrounded by ten small baskets (each 4”x4”x4”). When researching archival photographs, Goshorn noticed there were far more pictures of men than women, and the pictures of women were mostly identified as “Squaw of,” rather than by the women’s names. This is an insult; the word squaw in the Algonquin language means vagina. Goshorn selected ten photographs of anonymous native women for each of the small baskets. Using the modern technology of going on-line, Goshorn sent out a request for names of historical and contemporary Indian women that today’s women would nominate as worthy of remembering. Within 48 hours, she received the names of 700 women. Their names are printed on the red splints used for the inside weave of the small baskets.

A Cherokee proverb is displayed with the baskets: “A Nation is not reconquered until the hearts of the women are on the ground. Then it is finished, no matter how brave its warriors or how strong its weapons.”

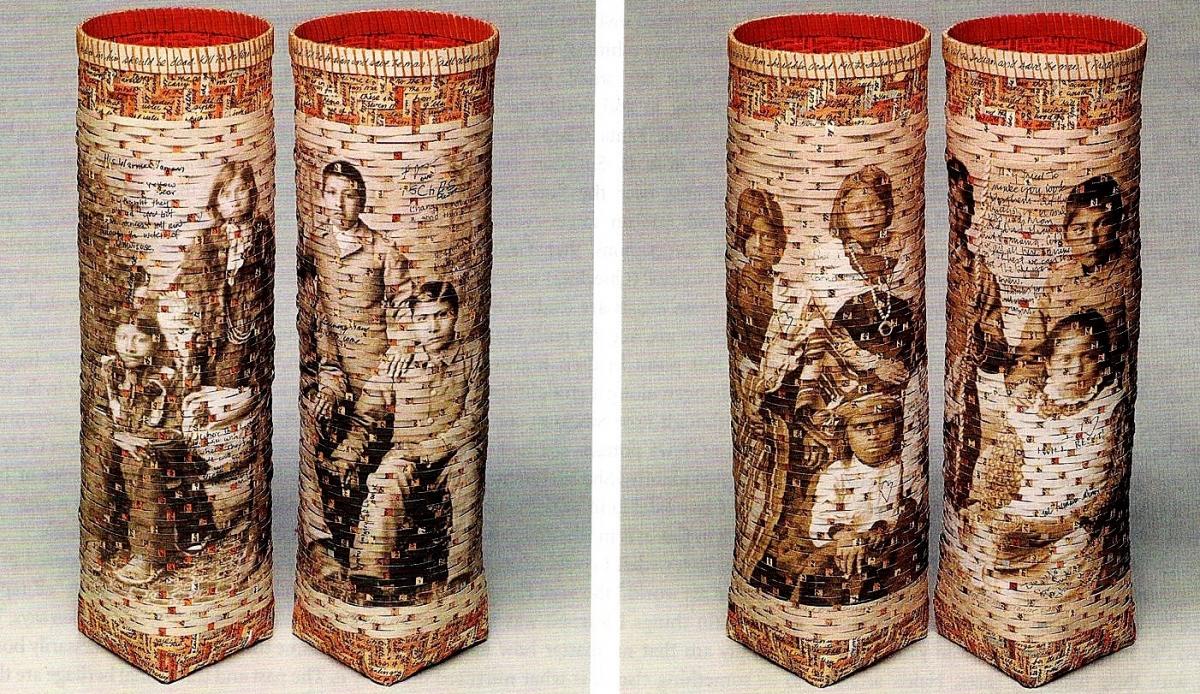

The National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC, exhibited and purchased Goshorn’s last work, “Resisting the Mission: Filling the Silence” (2016-2018) (21” x6.75” x7.5’’) (double weave). The work consists of seven sets of two baskets, one a “before” image when the children first arrived at Carlisle, and the other an “after” in their uniforms. School rules forbade the children to speak their tribal languages or practice their cultural traditions. Those who did, were punished harshly. Captain Pratt hired professional photographers to take the pictures, and he had the “after” pictures altered by lightening the children’s skin and padding their clothing to keep them from appearing malnourished. Around the top of the baskets is a copy of Pratt’s 1892 speech in which he stated that it was necessary to kill the Indian in the child to “save the man in him.”

The inside of each basket is woven from splints made of copies of the Carlisle rosters from 1878 until1918, when the school finally closed. The rosters contained approximately 10,000 to 12,000 names. On the school grounds is a cemetery with 200 children’s graves. Ten bodies have been repatriated to their homelands. Goshorn and her daughter visited the cemetery for the first time in preparation for making these baskets. They requested Native communities to write personal messages to the children, and to help collect the sacred plants of sweet grass, sage, and cedar used in funeral ceremonies. Goshorn and her daughter made bundles of the plants and notes, and they placed them on all 200 graves to purify the bodies, to drive out negative energy, and to attract good spirits.

Goshorn spent over two years making the baskets for the exhibition. She was able to attend the opening, but died from cancer one week later on December 1, 2018. Reflecting on the work, she stated: “Historical trauma still haunts native people as a result of this deliberate theft of language, family and culture. I hope this piece will give audiences–especially native people–an opportunity to overcome the silence that has been suffered for too long.”

Throughout her career she supported causes related to the environment, women’s rights, and Native American rights. An example is the basket “Defending the Sacred” (2017) (19”x17”x 6”) (not pictured), her response to the construction of the Dakota Access Pipe Line. The proceeds from the sale of the basket supported the Standing Rock Sioux legal fund.

November is designated Native American Heritage Month, honoring the history and the rich and diverse cultures of Native peoples. Shan Goshorn stated, “My work over the last 25 years has always addressed human rights issues, mostly those that affect Indian peoples today.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Jeffrey Ethridge says

A correction: Shan Goshorn grew up in Bel Air, MD. For those of us who live or lived in Bel Air, to say we are from Baltimore is an insult. She was one of my very good friends growing up from as far back as I can remember. After graduation from Bel Air High School and she went off to art school, I only saw her once when she was visiting Cherokee NC with her first child at the same time I was. We met by coincidence at breakfast. I had always planned to visit her when I took a driving trip out west. I miss her very much.

Jeffrey Ethridge, Arnold MD, former resident of Bel Air MD. 🙂