Like any other dreaded domestic chore, I had a long list of reasons for why I couldn’t devote time to index and label over a decade’s worth of the Spy‘s digital photography. At least that was the case until the pandemic hit in 2020. And in June of last year, having run out of reasons to procrastinate, I began the grunt work of reviewing and documenting those 15,000 plus images.

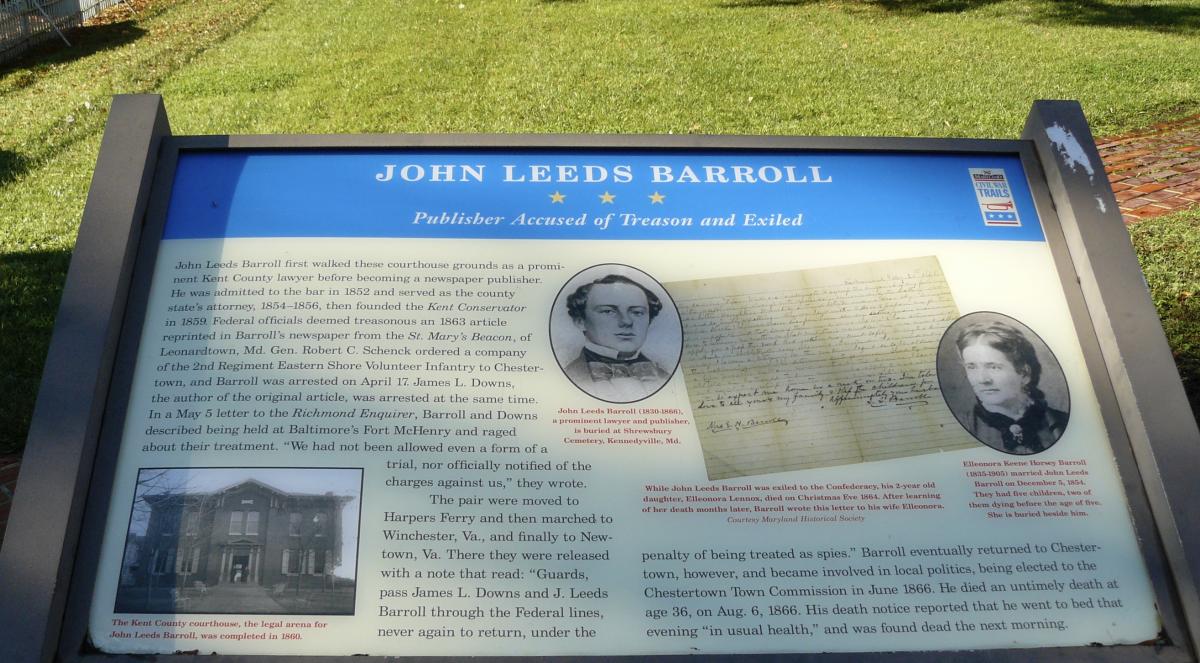

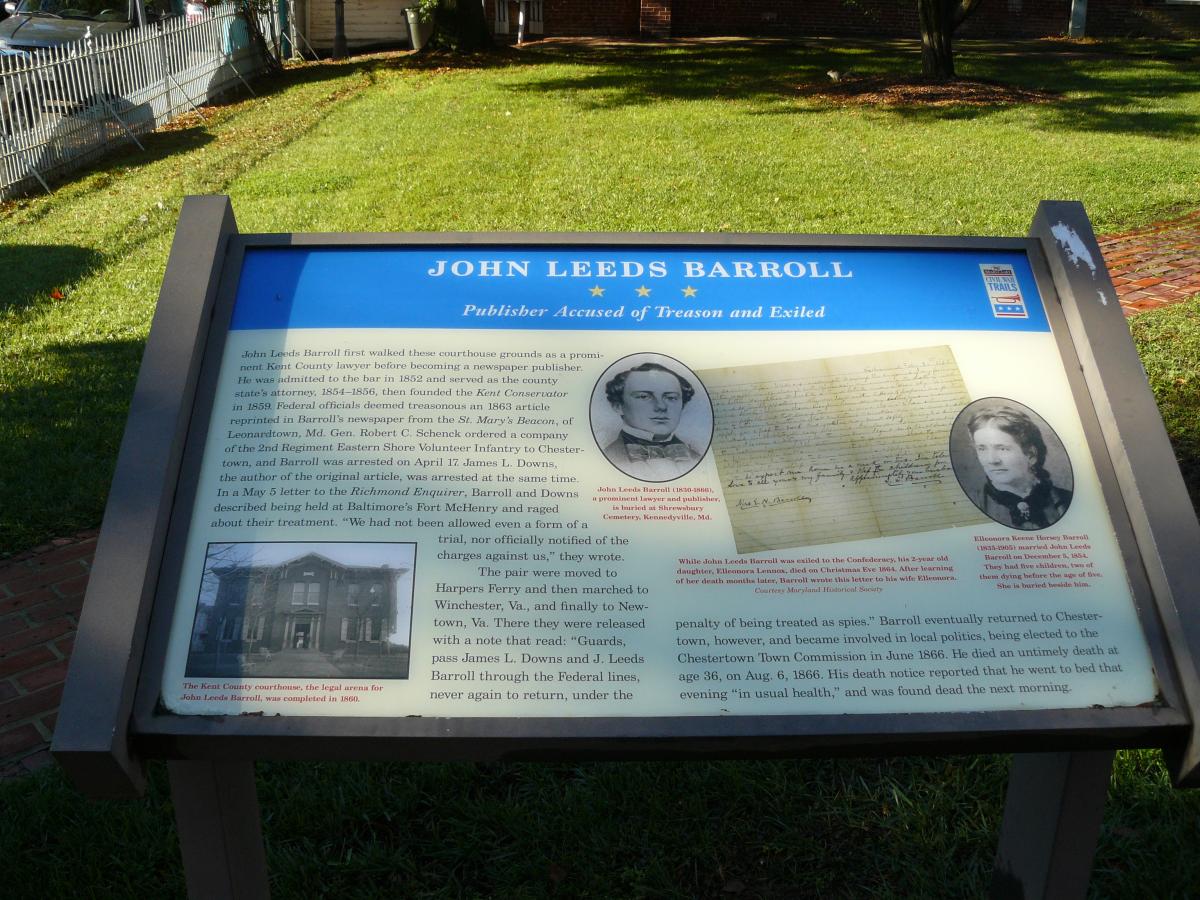

During this process, I came across the other day a photo I had taken in October of 2008 of an interpretive sign on the Lawyers Row side of the Kent County Courthouse lawn documenting the life and times of John Leeds Barroll.

With the headline above his name saying only, “Publisher Accused of Treason and Exile” this panel, apparently approved by the Kent County Commissioners, provides a short narrative and images of John, and his wife, Elleonora, noting his life as a lawyer, and later the publisher of the Kent Conservator, before he was accused of a treasonous activity of some sort in 1863. It goes on to describe how he was held captive at Fort McHenry, where he had faced harsh conditions, and later, his exile to the Confederate States of America, and finally his return to Chestertown.

I didn’t really think much about the sign, nor John Leeds Barroll, at the time I took the photo. My motivation that day was to collect images and factoids about Chestertown before I launched the Spy a few months later. And so, that image, and the thousands of others like it, has been gathering iCloud dust for the past twelve years in our electronic storage unit.

But as I was making my way through these seemingly endless photos, the Courthouse image for John Leeds Barroll popped up for documentation, And I finally read the narrative on the sign for the first time.

The instinct to read the panel came from my dual role of publishing the Talbot Spy in Easton, where for the past six years we’ve been covering the sad story related to the “Talbot Boys” Confederate memorial on that County’s Courthouse lawn. I was already interested in how counties go about deciding to use the sacred spaces surrounding their courts of law.

With all that in mind, I Googled “John Leeds Barroll” after looking at the photo. Since there was no mention of the circumstances for his ouster from the Mid-Shore, surely, I thought, there must be a fantastic backstory that would justify the inclusion of publisher John Leeds Barroll on the Courthouse Green.

Being a newspaper publisher myself, I had high hopes of finding a sterling story of an embattled country editor, willing to risk everything to protect freedom of speech. His only crime, according to the sign, was his newspaper’s reprinting an article originally published by the St. Mary’s Beacon on the Western Shore. Nothing more. And since on more than one occasion, the Spy itself has gotten into trouble for this kind of thing, fingers were crossed that John Leeds Barroll was a noble character.

Unfortunately, that optimism was not well-founded.

While it was true that Barroll’s rough treatment was caused specifically by the re-publication of an opinion piece, our less than informative Courthouse plaque does not make mention that John Leeds Barroll was an outspoken critic of emancipation himself.

In fact, his newspaper was so pro-slavery (his parents and his wife’s family owned slaves), that the Kent County News noted in 1861, “The ‘Conservator,’ … is doing all it can in this vicinity to keep alive the waning fires of secession.” Indeed, Barroll’s response on record was that the Union, under Lincoln, was made up of “bloodthirsty demons of abolition,” and later, “the cry of Union in Maryland or elsewhere means the attempt to subjugate the South. It means war, and above all, it means the emancipation of every slave …”

Perhaps historians should continue to debate the use of Habeas Corpus on the Eastern Shore during the Civil War, but it’s more than disappointing that this sign, standing on public property, with the intended purpose of educating the public, does not tell the reader the real truth about John Leeds Barroll — that he was a proud and well-documented racist.

While it remains a mystery to me why Barroll’s story would even justify its placement on the grounds of an American courthouse, whichever County Commissioners approved this sign did so knowing of its intentional ambiguity.

Is it any wonder that those fighting to tell America’s painful story of racism are outraged when places like Kent County become willing collaborators in glossing over such essential facts of history? For those who have been victims of America’s historically racist justice system, it’s just another example of how those in power control the narrative.

If the sign had more transparently noted Mr. Barroll’s role in advocating secession, and as a consequence, the high price he paid for these treasonous acts had been noted, there could be some rationale made (however weak) for retelling this story on the Courthouse lawn. Instead, it stands unchallenged in preserving the legacy of John Leeds Barroll as an independent newspaper publisher, not for his publication’s history of defending slavery.

It is this kind of whitewashing and carelessness that makes people distrust institutions and government. If your local courthouse stewards provide space to acknowledge people like Barroll and don’t respect the truth, it’s not a big leap to assume that the same lack of respect can be found inside the courthouse as well.

Dave Wheelan is the founder and publisher of the Chestertown Spy

Rosie Ramsey Granillo says

Great research! This reminds me of #SlaversOfNY – they’re researching and raising awareness about these relics hidden all around us. The Resistance podcast covered them in their episode “Lesser Known Creeps”

Kurt says

fascinating! i am befuddled realizing how much of my education was whitewashed as part of a school curriculum

Vic Pfeiffer says

Thanks for raising this ugly history and waking our sleepy sensibilities of how we as a people have not admitted and in fact in many subtle ways perpetuated our racist past. I hope we are at a time when we can truly come to grips with it. For instance, the James Taylor Justice Coalition at Sumner Hall is trying to initiate a community reconciliation of our 1892 Lynching.

Thanks for doing this research. Let’s get that historic sign down ASAP.

Virginia Davis says

I remember reading that plaque when I lived on Queen Street–unaware of all that was left unsaid. I hope Chestertown will remove it.

Barbara Snyder says

Removing it is the same as saying it never happened.

Maria Wood says

Thanks for doing this research and bringing the truth to light. This story, and the story-behind-the-story, present a perfect example of the many ways history is hidden, obscured, or overtly misrepresented. We need to know and understand all parts of our history before we can responsibly be proud of our town’s “historic charm.”

Peter Koch says

Just a thought, the Civil War Trails organization works with local entities to create these signs and then they are tied into a larger state-wide network that is designed to draw tourists and to excite people about the history around the Civil War. The past several years has seen growth in the network of signs as well as a reevaluation and reinterpretation of many of the signs that had been in the ground for a number of years. The Civil War Trails folks are heavily involved in that process at a number of sites currently.

My suggestion (as a board member from another state) would be to become involved in the entity who sponsored and helped develop the sign originally (and I don’t know who that is, sorry) and work with them to find a better, more inclusive story that you as a community want to share and be proud of.

Michael McDowell says

Most illuminating, Dave. I often read the marker while walking out little Dachshund, Jersey, and have wondered myself. There was pro-Confederate sympathy there, I could see, but I did not know the back story. A plaque/marker, beside the original one, would tell the larger story.

John Leeds Barroll IV says

As a direct descendant of John Leeds Barroll, of course I find this controversy interesting. His history is well-known in our family. His exile perhaps could have been properly litigated if habeas corpus had not been suspended by Lincoln; in my view the suspension of habeas corpus set a terrible precedent even though I think Lincoln was one of our greatest Presidents. Your readers should know the American Constitution’s prohibition of tainting the blood of descendants is alive and well: like the subject of your article, I am a lawyer. However, I have brought numerous civil rights lawsuits. I do not think the sign should be removed, as it is a part of Chestertown’s history. Our own values are shown to be weak if we feel the need to “burn the books.” I also do not believe the sign should be changed, as it is poor form to insult the deceased. I have no objection to a second sign as long as it would fully summarize his career rather than just emphasized the bad.