The place and the time feel so innocent as I look back. I’m not sure now if my memories of Oxford, where my sister, Perry, and I found ourselves over fifty-five years ago, are lifted out of the haze of time and dusted off, or if they are the fresh stencil of those hot summer days pressed onto imagination.

It was spring 1965. I was eight, Perry was eleven. Our beautiful mother, divorced from our father, had just remarried. Bill Pickford, a hotelier and sportsman from California, was the stepfather from heaven. He had six children from previous marriages and came with a floating sapphire blue Cadillac convertible. He moved to Washington (D.C.) after his second divorce to join his brother, Tom (later a St. Michael’s resident) in the running of two hotels they owned, one across from the White House and another on Capitol Hill. He and Mum met, and after a suitable courtship, married, and we’re off to the races, literally.

Our journey to Oxford began in mystery. Bill roused us from sleep at five one Saturday morning, and asked, “Are you coming?” “Where?” we asked. “Because we’re leaving in ten minutes,” was all we got. There was a long slender sailboat attached to his car outside. That was a hint. Neither Perry nor I had ever heard of Oxford, we didn’t know about Star Boats or the Chesapeake Bay or the lure of the open water. I remember the excitement of leaving Washington while the city slept, crossing the Bay Bridge, stopping in Easton to buy penny loafers at Cherry’s – into which Bill quickly stuffed dimes – pick up ice cream, and make our way to Oxford – all with the top down. Mum smiled at us in the rearview mirror, “New world, girls.”

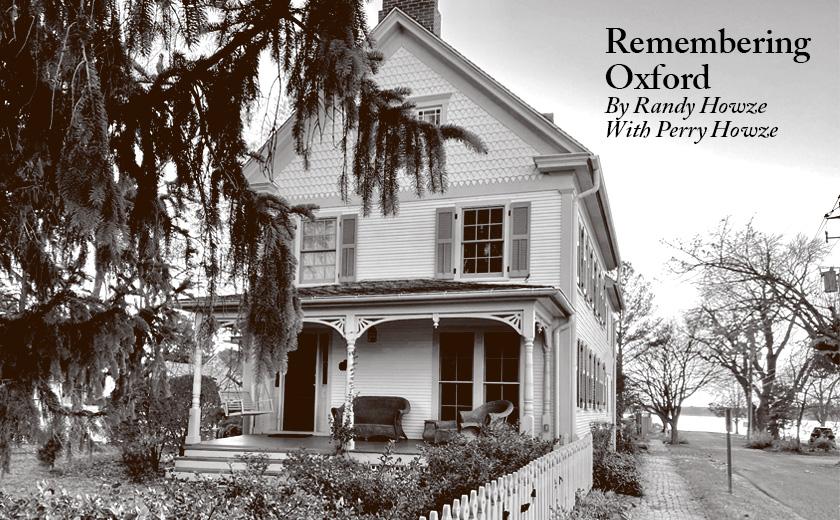

Bill had rented a house for the summer with a wide front porch on Morris Street, next door to the ferry captain, who had a white beard and a kind wife – a storybook captain. We were kitty-corner from the Robert Morris Inn, and a few steps up from the Tred Avon Yacht Club, which would become our second home. Bill imported four of his children from California in shifts – Perry and I suddenly had two brothers, one older, one younger, a sister of sixteen who had shiny hair that bounced when she danced to “I Get Around” by the Beach Boys, and another sister, my age, reeling from the rupture of her family. They came from what to us was a foreign land – Southern California – to be with their father. So while there were the static waves of unresolved emotional confusion in the air, we children had common cause: we had the days to pass in this quiet little place, strange to us all.

The world of sailboats opened before us. Sailboats are demanding mistresses and Bill’s boat – our boat – the Caprice – was now a member of the family. Bill asked Mum to be his crew for the summer, a wise move, with the small drawback that she didn’t know how to sail. So, he turned her into a sailor. They entered races and regattas, lost some and won some, as a collection of silver mugs with glass bottoms and the small blue and white enamel Tred Avon pennant testify. Bill was an exemplary sportsman – always good-humored – in victory and defeat.

This left Perry and me a lot of time on our own. We had a dinghy – a Dyer Dhow. We learned the basics of sailing, how to trim a sail, tie knots, and keep from getting our heads lopped off when tacking. We’d venture out onto the Tred Avon River, but never go very far for fear of capsizing and being swept out to sea.

It was a Summer of Jellyfish – the ubiquitous Sea Nettles – albuminous bell-shaped blobs with tentacles that stung when you brushed up against them in the water. They glugged around the surface in constellations, so swimming was risky. And they multiplied as the summer wore on. We were fascinated and horrified. Still we swam – off the dock at the yacht club – if only to make a game of dodging the nettles. I’m not proud of it, but we sometimes scooped them out of the water, set them on the dock for examination, where they would die by dehydration. And when you rubbed your fingers over the wood plank, it felt like silk where the sea nettle had been.

We swanned around in our bathing suits. Perry got her first two-piece, and would stand around the ice cream cooler at the yacht club hoping the son of one of Bill’s sailing buddies would notice, but no one ever did. We were often sent to the yacht club for lunch, where we would order whatever we wanted and it was understood it would go on the Pickford tab. And if no one was around, you just took a Coke or an ice cream sandwich, wrote it down on the mint green chit pads, and stuck it on the spike. We felt like we had the run of the place, as if the yacht club was there just for us.

The summer wore on, the long yawn of a sleepy town. I remember walking in bare feet along the unpaved sidewalks, up and down the main street. I don’t know that I ever knew its name. Our world was tiny, contained, and safe. Morris Street in my memory was wide and in spots, canopied with big leafy trees, though the expanse in my memory may be in contrast to my smallness then. Heading away from the water, about a two-minute walk on the other side of the street, was The Store. After the yacht club, it was headquarters. I’m guessing it sold more than penny candy, Lik-a-Maid sticks, frozen Milky Way bars, and our favorite, blue popsicles, but these were the draw for us. And Archie comic books. Several times a day, we’d go through the screen door, letting it slap shut, counting pennies won in the previous night’s round of Blackjack, then cross the street to the park that gave onto the water, though we didn’t swim from there. We sat at the picnic tables and read our comics. We tried to find mischief to get up to, but there was none to be found. The sameness of our days was enlivened by family dinners at the Pier Street Marina, a big open-air seafood restaurant with steel-topped tables where everybody sat with everybody, cracking shells and eating with our hands.

And there were lots of cheery, sunburnt grownups in rubber shoes and red shorts, who came to Oxford from I-don’t-know-where to race with Mum and Bill, then would show up at our house afterwards looking for alcohol. I remember fireflies and mosquitos, and playing on the street in front of the house in the evening, and liking the sound of laughter and clinking glasses coming from inside

We didn’t realize then that our Oxford summer would be one of only a handful of summers we’d have with Bill. He had cancer. He and Mum had discovered it on their honeymoon a year earlier. But he was in remission. I had no idea he was sick, and Perry, along with everyone else, had put it in the past, so we had the feeling, at least for the moment, that life had gotten whole.

Randy Howze and her sister, Perry Howze, are Washingtonians, and screenwriters, who now live in Mount Cuchama, California.

Billie Carroll says

Sounds like it could be the makings of a nice summer film.

Rick Bisgyer says

Days of summer, days of bliss…

Thank you!