This past weekend while many families were heading to the Maryland and Delaware beaches for summer fun, I headed in the opposite direction to Highland Beach on the Chesapeake Bay near Annapolis. My purpose was to visit this town that has a very special place in Maryland’s history. Before my move to The Eastern Shore in 2004, my required reading began with “Chesapeake” by James Michener and a biography of Frederick Douglass. “Cedar Hill” was Frederick Douglass’ home in the Anacostia neighborhood of DC and “Twin Oaks” would have been Douglass’ summer home in Highland Beach, Maryland, had he not died before its completion. I recently learned the restoration of “Twin Oaks” began in the mid 1980’s and was the residence of Annapolis architect Chip Bohl and his wife Barbara. Walking through this charming small beach town with houses stepping up the hills above the Town Park and beach along the Chesapeake Bay was a delightful architectural and historical tour for me.

From my online research, I learned that the history of Highland Beach began twenty-nine years after the Emancipation Proclamation during the time of the Post Reconstruction Jim Crow Laws. Major Charles Douglass, who was a Civil War Veteran and the youngest son of Frederick Douglass, lived with his wife Laura in Washington, DC. During a trip to Maryland’s Western Shore in 1892, they were refused service, solely because of their race, at the Bay Ridge, a grand Victorian style summer resort that was a popular destination for vacationers from DC and Baltimore. Charles Douglass began to dream of a summer haven free from the bigotry of the Jim Crow laws.

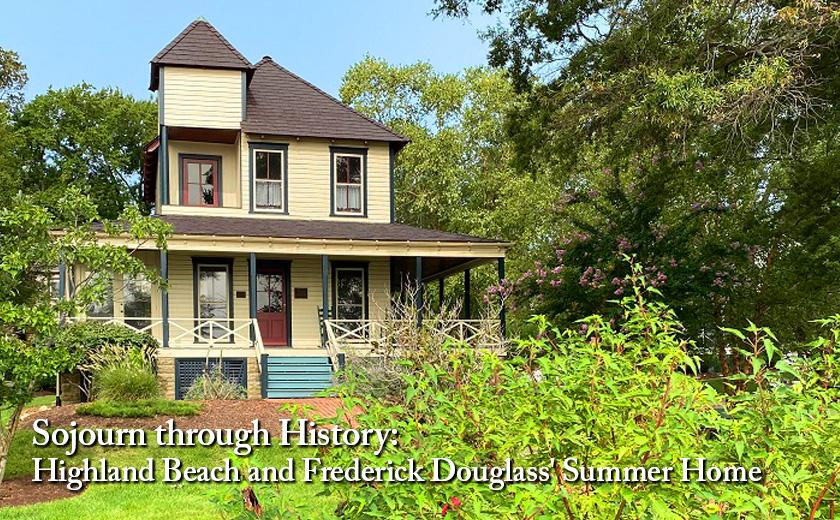

Across the Bay Ridge Resort on Black Walnut Creek was a property owned by a local black family. In 1893, after several months of negotiations and with some financial assistance from his father, Charles Douglass became the owner of a large parcel of the former Brashears estate in 1893 and became a developer. He created lots for family members and friends to build summer residences. A year later, Charles Douglass built Highland Beach’s first cottage for his family. He also reserved the prime corner lot for his father’s house, across from the shoreline park, beach and the Bay. Construction began and the house was christened “Twin Oaks”. The key design element was the second floor balcony, strategically placed with a direct view across the Bay. Frederick Douglass could stand there and savor his freedom as he gazed at the mouth of the Eastern Bay leading to the Wye River where he was born a slave.

The allure of 500 feet of a gently curved beach on the Chesapeake Bay and the proximity of Annapolis and DC to the Town soon became a gathering place for many of the well-known African Americans of that time and later years. As I gazed at the front elevation of “Twin Oaks”, I imagined the wrap-around porch would have been a popular gathering place for residents and guests who were the ”firsts” in their fields. If there had been a guest book at Twin Oaks, names listed would have included Judge Robert Terrell (one of the first municipal court judges in DC ) and his wife Dr. Mary Church Terrell (one of the first African American women to earn a college degree who later became nationally known for her activism for women’s suffrage and civil rights); Booker T. Washington (advisor to US presidents, author, educator and orator); Paul Lawrence Dunbar (novelist, playwright and poet; W E.B. Du Bois (author, civil rights activist, historian and sociologist); E. Franklin Frazier (author and sociologist); Paul Robeson (stage and film actor, concert artist and political activist); Langston Hughes (novelist, playwright, poet and social activist); Robert Weaver (first African American to be appointed to a cabinet position as the US Secretary of Housing and Urban Development) and Alex Haley, whose groundbreaking book and TV series “Roots” started a nationwide interest in genealogy.

Through the years, “Twin Oaks” passed through several generations of the Douglass family until one day it caught the eye of Annapolis architect Chip Bohl and his wife Barbara, who were involved with the preservation of Anne Arundel County’s historic structures. Chip was intrigued with “Twin Oaks” association with Frederick Douglass and on summer drives he and Barbara would pass by the house and soon began to notice its slow exterior decline. They inquired about the house in the hope of helping to promote its preservation. One of Douglass’ descendants still owned the house and sold it to the Bohls. They acquired the house in the mid 1980’s and began its restoration per the National Park Service Standards of Rehabilitation to its 165 appearance including the original exterior color scheme.

To protect the historic structure, they raised the house’s main floor four feet above FEMA’s designated floor level. The exterior wood siding was carefully removed to examine and repair the wall cavity and add insulation before the siding was restored to its original coursed positions. The couple were greatly relieved to discover on their first walk-in that the interior of the house required little alteration. The wood floors were in good shape and much of the 1895 glass was still intact. Since the house had been built as a summer home, the interior wall and ceiling finishes were triple bead pine boards instead of the plaster prevalent at that time which would not have withstood years of temperature differential in unheated spaces. The bonus was that since its original construction in 1894, the pine boards had acquired a beautiful patina that required very little upkeep. Installing HVAC, updating electrical and plumbing were the final touches to make the summer house the Bohls’ year round residence.

The Bohls unselfishly understood they were temporary stewards of “Twin Oaks” and the house belonged to the people of Maryland and to the Nation. To preserve and secure the future of “Twin Oaks”, the Bohls enlisted the help of Donna Ware who at that time was the Chief Preservation Officer for Anne Arundel County. She was instrumental in listing the house on the National Registry of Historic Places in 1991. The Bohls subsequently sold the house to the State of Maryland in 1995 and it was deeded to the Town of Highland Beach. The property is now the Frederick Douglass Museum and Cultural Center. The Bohls’ wise decision to raise the house’s foundation during their restoration saved the Museum collection from the aftermath of the storm surges of Hurricane Isabel in 2003.

Highland Beach is believed to be the first African American summer resort in the United States. When Highland Beach was incorporated in 1922, it became the first African American municipality in Maryland. Today it is home to both full time and summer residents who zealously continue not to permit any commercial establishments within the Town limits. Many of the houses are still owned and occupied by descendants of the original homeowners. On the day I visited, I enjoyed strolling along the street by Town Beach with its park and pier for residents and their guests only and enjoying the salty air and the Bay breezes. As an architect, I admired the mix of newer houses and the original houses with markers proudly celebrating its first residents in this most intriguing Town so proud of its history. I look forward to visiting Highland Beach again when the Frederick Douglass Museum and Cultural Center is once again open.

“Twin Oaks”, The Frederick Douglass Museum and Cultural Center, Inc., is located at 3200 Wayman Avenue, Highland Beach, MD. The Museum is open by appointment only but is temporarily closed due to Covid. The Museum hopes to reopen to visitors in the spring of 2021. For further information about the Town of Highland beach and the Museum, visit the Town website at www.highlandbeachmd.org.

Restoration of “Twin Oaks” by Chip Bohl of Bohl Architects, , www.bohlarchitects.com, 410-263-2200, [email protected]. Photography by the author and Chip Bohl.

Jennifer Martella has pursued her dual careers in architecture and real estate since she moved to the Eastern Shore in 2004. Her award winning work has ranged from revitalization projects to a collaboration with the Maya Lin Studio for the Children’s Defense Fund’s corporate retreat in her home state of Tennessee.

Zoa Ann Beasley says

Totally intrigued by your very descriptive story of Highland Park’s rich history. I wanted to jump in my car and experience this gem. So interesting. Great reading of history.