It’s raining, today. I’m ok with it. It reminds me of those days when, as a boy, I went on summer vacations.

As a child, vacation months were times of freedom, of release. We’d do as we please, swim, play stickball, roam aimlessly through the neighborhood, free from the eyes of teachers and other wary grown-ups whose ubiquitous presence cast a constant pall over our youthful exuberance. Their presence confirmed that we were not really free, as we’d been told Americans are supposed to be. Vacation was a blessed breather, living the American dream, within minimal constraints.

We frequently vacationed in rural areas of New Jersey. We stayed in small cabins. The cabins were crude but pleasantly rustic, their amenities assembled throughout the cottage like after-thoughts. Jackets hung on large nails, as did pots and pans; screen doors closed – almost. We’d walk on moth eaten scatter rugs barely covering undulating floors that bore remnants of food and water stains left long ago. I liked the cottages.

The cottages were small, built along lakes. I was always swimming and if not, I liked walking by myself through pathless the woods wearing my moccasins fancying, myself the Native Americans I’d read about. My father collected a massive array of Indian arrowheads which I would finger through, amazed at how they were both roughly hewn and still had a smooth finish like a turtle shell.

On rainy days, we would go to the Dry Goods Store as we called it. It was similar to today’s convenience store but with a more eclectic stock. It carried odds and ends, milk, bread, household items, clothing, yarn, kerosene, and kid’s stuff like model airplanes, a potpourri of arts and crafts, coloring books, and sketch pads. We’d stock up for the day, our stash easing the pain of our enforced confinement by the rain. My choices were mostly crayons and coloring books. Others were pads with blank pages. I suspect my affinity was a metaphor of freedom, in the sense that the blank sheets of paper were open invitations to draw anything that might suit me. I even wrote little short stories with pictures and since it was the war years, I’d copy pictures of war-weary Willy from Bill Mauldin’s classic war documentary, Up Front. I once drew a square rigger under full sail. It was beautiful.

On August of 1945, we were staying at a lake. On August sixth, I learned the atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima. My uncle, a chemist, explained to us the terrifying power it yielded and the insidious effects of lingering radiation. It was a first fall from innocence associated with a rustic cabin in the woods of New Jersey.

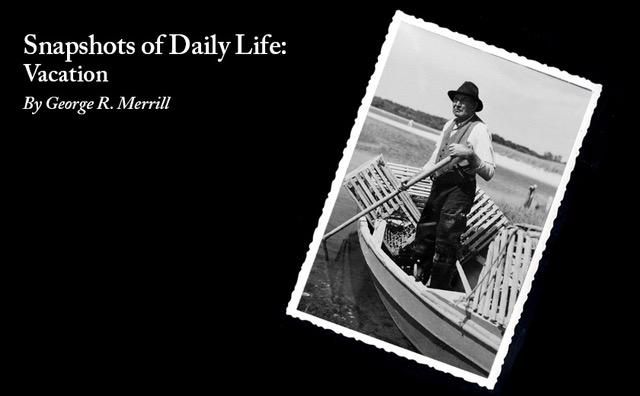

One summer we vacationed in the tiny village of Robinhood on the coast of Maine. I recall distinctive smells that summer; the ubiquitous aroma of pine pitch and the smell of salt water, lobster bait, and gasoline mixed together. Mr. Dutton, a lobsterman took me out on his boat to pull lobster pots. The motor was a small inboard, an ancient Palmer, one cylinder. Mr. Dutton called it fondly, his “one lunger.” He started it by rotating its external fly wheel: on the first turn the engine just hissed at him; on the second and third turn it started burping and finally turned over with a slow and steady cadence that thumped like a rapid heartbeat.

There was always some water in the bilge and as he emptied his lobsters into the boat, chum would fall into the water and mix with the gasoline. Combined with the cool salt air, it created a scent I found pleasing.

Vacations in Maine differed from vacations in New Jersey. In Maine, we had to dig our own cold pit. There was no electricity. We had an ice box but ice was not always available. To ensure that our butter and milk survived the hiatus between getting blocks of ice for our ice box, keeping the milk in a hole deep in the ground insured its longevity. I dug the cold pit. The job was too much like the chores that I had at home maintaining our victory garden. Vacationing in Maine, tedious at times, was still a unique experience. My brief cruises with Mr. Dutton, motoring between the islands, with a boat filled with live lobsters, was nothing less than exotic.

I suspect there are those in the land today who know not the release one feels sitting in the legendary outhouse of yesteryear. It was very ripe place. Our cabin had no indoor plumbing and we depended on an outdoor well for our water. One summer I was assigned the unenviable task to rake level the mounds of effluence that piled up like small hills just below the hole where an occupant sat. Then I had to apply generous portions of lime which to this day I’m not sure why. So much for the good old days and being the older brother.

During this coronavirus, I am confined to a house in the country by the water, just like summers as a boy. I can do anything, as it was the case in my boyhood summers with the added perks of refrigeration and indoor plumbing. Big boxes have replaced the homey Dry Goods Store and super markets have eclipsed most mom and pop grocery stores.

After Hiroshima, I wondered what would become of us. I have similar thoughts today; what will it be like when the pandemic ends. Seventy-five years after Hiroshima, the world is still living anxiously.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Joy Kim says

I am glad you see Hiroshima as a marker of modern anxiety for the whole world on this 75th anniversary. “Peace is not the absence of war but the absence of fear.” (Friends Committee on Nat. Legislation)