Lady Bracknell (Debra Ebersole) lectures the lovers, Cecily and “Ernest” on left and “Ernest” and Gwendolyn on right with Rev. Chasuble looking on.– Photo by Jane Jewell

Oscar Wilde’s irreverent comedy of manners, The Importance of Being Earnest, now playing at Church Hill Theatre, offers a tongue-in-cheek look at Victorian England. Directed by Sylvia Maloney, the play reminds us that the Victorians, who have the reputation of taking themselves far too seriously, also had an irrepressibly silly side – one that Wilde brings into delicious focus. Even the play’s subtitle, “A Trivial Comedy for Serious People,” takes a sly poke at the disconnect between the Victorians’ self-image and their tendency to elevate the minutiae of life into major social and moral crises.

Oscar Wilde in 1889 at age 35 — photo from Wikipedia

Wilde (1854-1900) was born in Dublin, the son of two Anglo-Irish intellectuals. He spoke fluent French and German at an early age and studied Classics first at Trinity College, Dublin, then at Oxford. Two of his Oxford tutors, Walter Pater and John Ruskin, introduced him to aestheticism, a movement often characterized as “art for art’s sake.” Wilde became one of the major proponents of the movement, writing poetry, essays, and journalism distinguished by their biting wit and stylistic elegance. His only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, was written in 1890.

Wilde turned to the theater in the 1890s, producing a string of popular comedies that combined witty dialogue, polished structure and satire of the leisure classes. Earnest, written in 1895, seemed at first to be a major triumph for Wilde. However, a quarrel with the Marquess of Queensbury, whose son was Wilde’s lover, ended with Wilde’s being arrested and imprisoned for homosexuality – still a criminal offense in those days. The scandal led to the play’s original London run being closed after only 86 performances; a New York run closed after 16 nights.

However, the play survived the scandal, and over the years, it has become one of the best-known of Wilde’s writings. It has received numerous revivals since its debut, including three film versions. In 1995, one critic called it “the second most known and quoted play in English after Hamlet.”

The plot follows two young men, John Worthing and Algernon Moncrief, each of whom leads a sort of double life. Worthing has invented an imaginary brother, Earnest, who gives him an excuse to visit London when he grows tired of life in the country – and whose name he assumes during his city visits. Moncrief, for his part, has invented an invalid friend, Bunbury, whom he pretends to visit in the country when city life bores him. The audience learns this in the opening act, set in Moncrief’s London apartment. We also learn that Worthing is in love with Moncrief’s cousin, Gwendolyn Fairfax, who comes to visit with her mother, Lady Bracknell. And Moncrief learns that Worthing has a young ward, Cecily Cardew, living at his country estate.

The plot develops as Moncrief decides to visit Worthing’s country home to meet Cecily, pretending to be the imaginary brother Ernest. This leads to hilarious consequences as Worthing returns home to discover his friend’s surprise visit – but we won’t give away the plot. Go see it and find out!

Maloney has put together a talented cast that includes both Church Hill regulars and several newer faces.

Gwendolyn played by Christine Kinlock and Mr. Worthing played by Howard Mesick — Photo by Jane Jewell

Howard Messick, a familiar figure on both the Church Hill and Garfield stages, takes the role of Worthing. One of the best comic actors on the local scene, Messick is a good choice for the character, drawing on his unparalleled ability to mug. He rolls his eyes or waves a hand in exactly the right way at exactly the right moment.

John Beck, previously seen in a number of supporting roles at CHT, takes the major role of Moncrief – and does an outstanding job. He presents a veneer of sophistication that highlights Wilde’s witty dialogue, which he delivers crisply and clearly. One hopes he builds on this appearance to take on more leading roles in the future.

Christine Kinlock, another regular in local theaters and in Shore Shakespeare productions, is convincingly aristocratic as Gwendolyn, who declaims that she can only marry a man named Ernest. Fortunately, her lover is named Ernest. Or so she thinks. But Gwendolyn is always sure of what she thinks. Except when she isn’t. And she isn’t bothered by any apparent self-contradictions. She pretends to be a dutiful daughter while all the time scheming to be alone with her Ernest. Kinlock does a great job of conveying the faux sophistication of the character.

Cavin Moore, who has been the choreographer for several CHT musicals (and who played the role of the fiddler in Fiddler on the Roof), is cast as Cecily, the young ward of Mr. Worthing. In contrast to Gwendolyn, Cecily is a country girl, who has led a sheltered life far from London. But now she is bored with her school-room studies and dreams of adventure and love. She wants an “Ernest” of her own. She shows that she can be conniving, too, in order to win at love. Moore is captivating as the naive yet clever Cecily.

The plum role of Lady Bracknell is played by CHT veteran Debra Ebersole, who truly looks the part, especially in the preposterous hat she herself designed for the character. Ebersole sails onto the stage as the pompous and self-important arbiter of society, Lady Bracknell, mother of Gwendolyn. Lady Bracknell knows everything, she’ll tell you – what everyone should wear, what they should say, and most importantly, who they should marry. Ebersole carries all this off in grand style.

Mr. Moncrieff and his aunt, Lady Bracknell; Merriman the butler in the background — Photo by Jane Jewell

Sheila Austrian is very good as Miss Prism, the stern schoolmistress with a secret in her past. Miss Prism tries to make Cecily take her studies seriously but she also has a soft heart toward her bored pupil and a soft spot for the local vicar.

The part of Rev. Canon Chasuble is played by Brian McGunigle, who took the part on short notice after the actor originally cast had to drop out of the production. McGunigle does such a convincing job that it’s hard to believe he wasn’t there from the beginning.

Sheila Austrian as Miss Prism and Brian McGunigle as Rev. Canon Chasuble — Photo by Jane Jewell

Frank St. Amour, Ronald Speedy Christopher Jr., and James Johnson do solid jobs as the servants, who, by the way, are probably the most sensible characters in the play. And you can tell that they see the silliness of their supposed “social betters.” Nicely done.

The play’s period flavor is greatly enhanced by the gorgeous Victorian costumes, created by Tina Johnson. The set – designed by Tom Rhodes and built by Rhodes, Jim Johnson, and Carmen Grasso, provides the perfect background for this comedy of manners. The scene moves from an elegant apartment in London to the beautiful, rose-covered garden of a country house.

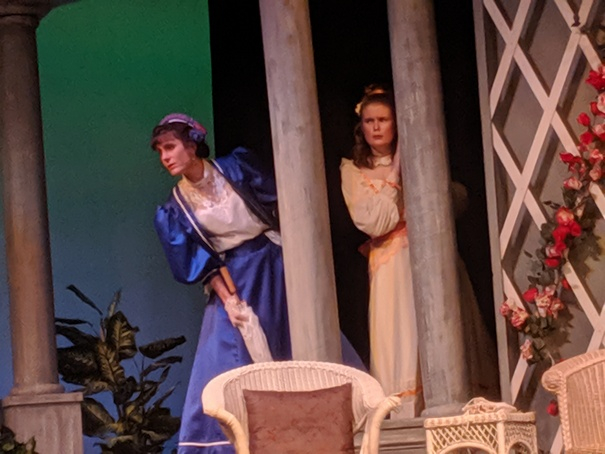

Gwendolyn and Cecily spy on their would-be fiances — Photo by Jane Jewell

The play also shows its period in that the pace is noticeably slower than many more modern offerings. Wilde reportedly asked his actors to deliver their lines, no matter how absurd, in a completely serious tone. Modern plays might go for a little more overt clowning. Still, the wit most definitely comes through. The action is in the dialog, the witty phrasing, and the parody of a pampered upper class.

This is one of the English theater’s great comedies– and is social satire at its best. It’s to Church Hill’s credit that it has brought this classic play to the local stage. In fact, this entire Church Hill season has been unusually adventurous, ranging from period pieces like Earnest and its French contemporary A Flea in Her Ear to striking but less-familiar modern plays like the striking 33 Variations – not to forget the brilliantly-staged Jesus Christ Superstar. A season any theater company could be proud of.

The Importance of Being Earnest runs through Nov. 17, with performances at 8 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays and at 2 p.m Sundays. Tickets are $20 general admission; CHT members get a $5 discount, and student tickets are $10. Call the theater at 410-556-6003 or visit the CHT website https://www.churchhilltheatre.org/ for more information or to make reservations.

Photos by Jane Jewell

Cecily Cardew, Mr. Moncrief, Lady Bracknell, & Mr. Worthing — Photo by Jane Jewell

Mr. Worthing (Howard Mesick) and Mr. Moncrief (John Beck) — Photo by Jane Jewell

Mr. Worthing is not sure he approves of Mr. Moncrieff kissing his ward Cecily — Photo by Jane Jewell

Cecily and Gwendolyn — Photo by Jane Jewell

Cecily and Gwendolyn check their diaries — Photo by Jane Jewell

###

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.