Editor’s comment: Memories can trick us, regardless of age, good intention, clarity of mind…or “what’s true” when surrounded by a world of confusion. Factual presentation, especially in memoir writing, is essential to its believability. Here is how one established author views it, in the current “Delmarva Review.”

Memory is a wonderful, treacherous thing. It traps us in emotions we cannot escape with mere reason. No argument will convince anyone that a particular memory is false, especially when that person has decided to write a memoir. As their collaborator, I share my own struggles with remembrances of things past to gently point the way toward more reliable storytelling.

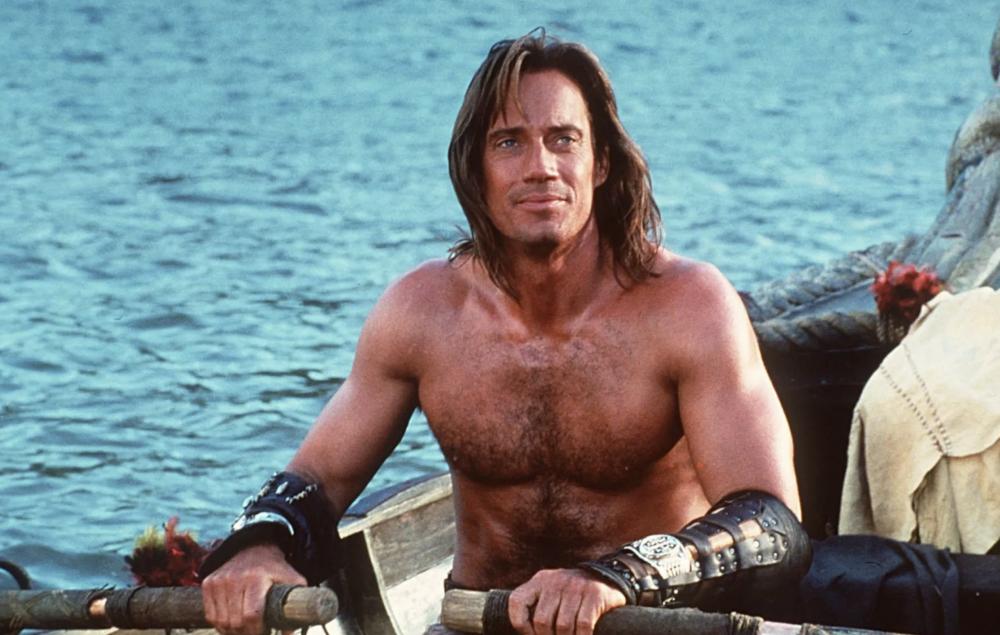

I recall clearly an episode of Murphy Brown about her affair with a younger man, played by Kevin Sorbo. A former Arrow shirt model, Sorbo’s astonishing good looks, and “aw shucks” style were both endearing and a perfect foil for the star’s caustic wit. Not that his reactions mattered much. The camera barely glanced at him when she warned, as they prepared to undress together for the first time, “Warning, contents may have shifted during flight!”

My recollection of the episode is vivid, despite knowing that Kevin Sorbo has never been on Murphy Brown. The actor who played Murphy’s lover was Scott Bakula, who, aside from being white, male and fair, doesn’t resemble Kevin Sorbo much at all. (They did both star in TV space operas).

Yet, I can’t cut Kevin Sorbo out of that memory and splice Scott Bakula into it. If my provably false memory is so tenacious, what other errors do I carry around?

So, when I write anything that I want people to believe—which is most of what I write, I test it with something more than my memory. Why does a character say that? How did that event take place? Who is the instigating force in that scene?

Sometimes, this requires external research. Does a character appear haughty because of what she is wearing? Is it a veil, a corset, high heels, a uniform, a badge, a crown, an overcoat, a gown, a glare? Is that an accurate reflection of the character’s position, emotion, economics? Did she borrow the crown, or have the veil thrown over her? Is she on that balcony because she is a princess or the cleaning lady? Why did the archduke go down that street?

Sometimes, I must test my writing with self-criticism, which is harder. Am I writing this because I angry, shallow, stupid or (worst of all) repeating something I read, came across on NPR or overheard in a bar? Is my brilliant, original thesis nothing more than the crap Matt Damon railed against in Good Will Hunting

This practice has saved me from hitting “send” (unfortunately, not always) after writing those late-night email rants the flesh is heir to. More often, though it has reminded me of the other failure of memory: the failure of memory.

On my hard drive, there is the beginning of a short story. It sets up nicely, creates tension, location, character and plot. I remember writing it, where I was (the Palomar Hotel in Los Angeles), when it was (fifteen years ago, winter, on a business trip), and remember clearly that the entire story was so perfect in my mind that I made no notes or outline.

The three hundred words are polished. This is not a first draft. I saved it under an odd file name, however, and lost track of it. When I finally found it, I had forgotten that perfect story. No amount of hair tearing could bring it back.

Periodically, I reread it, once even at the Palomar, looking at the places and things that figure in the story. Nothing triggers the memory. Is it gone forever, like Hemingway’s first novel? Even if I finish it someday, the lost tale will always be better.

Neurologists tell us that the story is still there, in my memory, with Kevin Sorbo in a role he didn’t play, with friends I can’t recall and life events so profound I can no longer conjure them up. These bookends—memory’s tricks and its utter failures—are constant obstacles to writers. Better to admit this at the outset, research the gaps, and go forward with humility.

How we sort through my memory, finding, editing, and sharing the things that are there, measure our skill as writers. It requires a certain amount of cold-blooded realism, as well as appreciation of the audience, to know what to write and what needs to be left unshared.

But that is a whole other essay.

_______

D Ferrara’s essays and short fiction have been published in numerous journals. Her screenplay “Arvin Lindemeyer Takes Canarsie” was Outstanding Screenplay in Oil Valley Film Festival and her play “Favor” won Outstanding Production of an Original Play, NJ Act Awards. She received a M.A. in creative writing from Wilkes University, J.D. from New York Law School, LL.M. from New York University, and a B.A. in theatre from Roger Williams.

“Delmarva Review” publishes the best of original new nonfiction, poetry, and short stories selected from thousands of submissions annually. The independent, nonprofit literary journal is partially supported by a grant from the Talbot County Arts Council with funds from the Maryland State Arts Council. The print edition is available from Amazon.com and Mystery Loves Company, in Oxford, and libraries. Website: DelmarvaReview.org.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.