I’ve been reading The Oxford Book of English Prose. Marianne Whitcomb, of blessed memory, for years the faithful servant of the St. Michaels Library, gave it to me years ago. I hadn’t read it until recently. I suspected the essays might be too stuffy for me. They weren’t.

As an Episcopal priest who spent half his professional career working with Methodists, one essay particularly caught my eye.

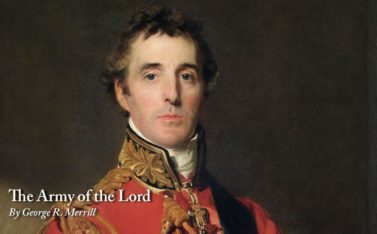

In 1790, Sir Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, wrote to Lt. General Calvert complaining about the quality of military chaplains in the British Army. In his view, only second-rate Anglican priests were appointed as Army chaplains, and worse still, most were retirees.

Sir Arthur was concerned that the soldiers receive better “religious instruction” and that a better quality of chaplains was critical for the “greatest support and aid to military discipline and order.”

Sir Arthur told the General he believed there was one particular cause weakening military discipline and order. It was not, as you might expect, womanizing, brawling or heavy drinking; it was Methodists.

Sir Arthur wrote: “It has, besides, come to my knowledge that Methodism is spreading very fast in the Army.”

“There are two, if not three, Methodist meetings in this town of which one is held in the Guards. The men meet in the evening, and sing psalms. And I believe sergeant Smith now and then gives them a sermon.”

Sir Arthur urged the general: “here and in other circumstances we want the assistance of a respectable clergyman . . . to moderate the zeal and enthusiasm to prevent the meetings from being mischievous.”

Sir Arthur believed that who would be better suited to dampen the enthusiasm and take the energy out of religious worship more than a stodgy and respectable Anglican priest? Anglican clergy, and their American counterparts, Episcopal priests, unfortunately have had a reputation for being elitist and snooty.

I am here to say it’s a new day.

I can speak with authority on this matter – not as it relates specifically to Methodists in the military, but from this respectable Episcopal priest’s experience as having been on the staff of a Methodist church for half of my professional career. I served the psychological needs of clergy in the Baltimore Conference of the United Methodist Church. Did their enthusiasm compromise my responsibilities? No. Did their zeal make any mischief for me? No way. Did their lusty singing of psalms (mostly it was hymns) in any way divert me away from my responsibilities? Absolutely not.

Quite to the contrary, I was enchanted, and at times inspired by Methodists.

My initial contact with Methodism in this region was with Bishop James Matthews, one of the great visionary clerics of the era. I interviewed with him for the position of assistant director of pastoral counseling services sponsored by the Baltimore Conference of the United Methodist church. Bishop Matthews studied the life of Gandhi, was a committed activist for social justice and a great leader in civil rights. He was deeply concerned for the mental health and well-being of his clergy. He was easy with the thought of an Episcopal priest holding the appointment in a Methodist agency, and in fact, welcomed the ecumenical implications.

I remember feeling awed by the friendly and matter of fact way by which he spoke with me knowing that he was one of the spiritual giants of the day.

I received his blessing for the position. I would be working from Grace United Methodist Church in Baltimore. The minister there was also a celebrated voice in Methodism, Dr. F. Norman Van Brunt. He had served as the Associate Chaplain of the U.S. Senate. He warmly welcomed me on the staff of Grace Church. Over the years I grew deeply fond of his courtly manner, and his personal dignity and warmth.

It’s worth noting that Methodism took off on the Eastern Shore precisely because of the “respectability” of Anglican clergy who had been on the shore prior to Methodism. They tended to be elitist, entitled and heady in their sermons, not to the taste or farmers and watermen. Methodist preachers, on the other hand, were earthy and inspiring and particularly articulate. They were just folks and fire breathing preachers, like the local preacher Joshua Thomas known as the ‘Parson of the Islands.’ Preaching to farmers and watermen from the bow of a pungy, Thomas stirred the souls of working men and brought many Shore folk to the Lord.

Camp meetings were held regularly near Crisfield. Methodist preachers came from afar to save souls. Apparently, in addition to the religious fervor generated at the meetings, other passions were inadvertently aroused, leading one local observer to comment on camp meetings that, “more souls were begat than saved.”

One Methodist institution, not mentioned in religious literature, is the Methodist “church supper.” The Episcopal Church’s coffee hour is small potatoes by comparison. During my interviews for the position, I was taken to several church suppers in parishes in southern Maryland to meet regional clergy. The Methodist church supper falls short only to the Messianic Banquet to which, bye and bye, we will all be invited. It is memorable for its delectable fried oysters, crab cakes, ham, Maryland fried chicken, mashed potatoes, green beans, corn on the cob and especially the fast disappearing dish of my grandmother’s day, stewed tomatoes. Attending three of these suppers clinched the deal. I was in.

Since Methodist preachers are abstemious and don’t drink (in front of each other, anyway) the closest they come to serious decadence is the church supper, and I haven’t even mentioned desert, which is often homemade apple pie topped with ice cream.

Suppers to die for? Medically speaking, yes.

The dinners are calorically lethal. Methodists should die young from clogged arteries. Not so, I learned later from one study I read on longevity among clergy. In fact, Methodist clergy live longer than average among clergy. So much for fruits and nuts.

My years serving the people at Grace Church and in the Baltimore Conference were treasured times. I also gained weight.

Speaking of weighty matters, today ecumenism is the wave of the future. If our denominations don’t find ways to cooperate, to work and pray together, I think we will all become lost souls.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.