I don’t think of personal achievements in the same way I once did. Then, my successes were all about me, about my competence and superb abilities. Now I can see those triumphs had little, and often nothing to do with me. I hadn’t seized the day; the day seized me.

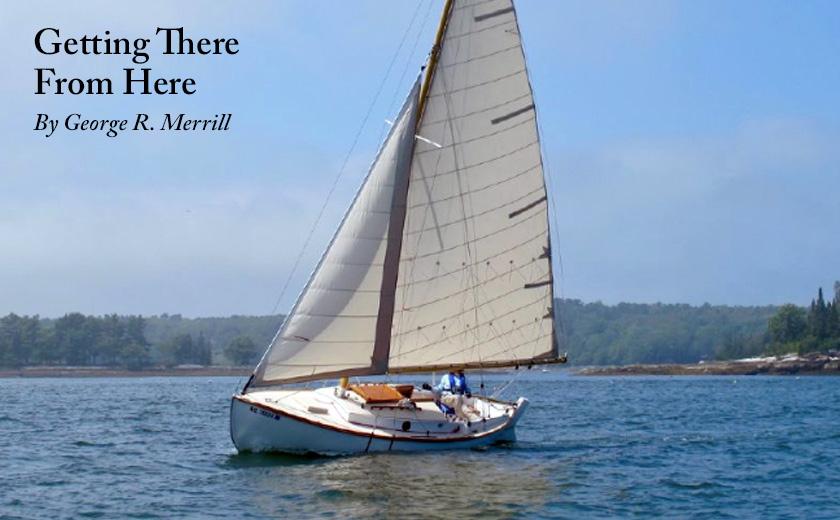

An episode occurred over fifty years ago. It involved sailing.

In a twenty-one-foot sailboat, I sailed from Westbrook Connecticut, across Long Island Sound to Orient point, the Eastern End of Long Island, then through Plum Gut and down into Peconic Bay.

I had been anxious even thinking about it. I planned the course scrupulously, almost obsessively. I used the dead reckoning method. It’s standard navigation, a way of charting a course from a known location and advancing it to a new one. The calculations include estimating the boat’s speed, the compass course, gaging the force of wind, waves, and monitoring the set of currents and most crucially of all, timing. Basically, it’s going from here, hoping to get there, or making an arrival as close to ‘there’ as reasonably possible. Finding one’s way over open water has always been an iffy business, until the arrival of the GPS. Since then it’s been duck soup.

I’d once read how, in the nineteenth century with only a compass, a sextant and an old alarm clock, Joshua Slocum circumnavigated the globe. I thought I, too, was about to do something if not exactly the same, a junior version of it. I fancied myself, a Joshua Slocum, the hot dog of Long Island Sound.

The challenge was to arrive at Plum Gut at full ebb, when the incoming flood tide would carry me into Peconic Bay, giving me a free boost, increasing my speed in the water by possibly 10 knots. The current tore through Plum Gut. Going with the flow was the only way to go especially since I was on a 21-foot sailboat with only a 12-horse outboard.

I was thrilled when I completed the trip. For years I thought of it as a signature event of my life. In retrospect, it was not all that eventful, even dull at times, as I had to motor frequently. The wind was light and sporadic, the Sound mostly calm. The day was comfortable; even in the hot sun the beer remained cold in the cooler and we made Plum Gut right on schedule.

So why was this event so indelibly etched in my memory? It was a time in my life when things worked out exactly as I had planned; I aced the task I set for myself. My skills and planning acumen acquitted me; everything came off like clockwork.

Truth be told, I’d only exercised appropriate care. That I engineered this successful journey is really an illusion; had there been a squall, strong shifting winds, or taking on any more water from a hull fitting that I later discovered had cracked and was leaking badly – any of which could have changed everything.

Reckoning my success as something I achieved on my own is a diagnostic indicator of spiritual vacuity, self-deception in the service of supporting the ego. It’s a variation of “It’s all about me.”

If I’d been aware of all the other natural forces then unknown to me contributing to this successful sailing adventure, I wouldn’t be feeling self- satisfied, I’d be feeling grateful.

Of course, I should be pleased that the trip went well but for a very different reason from my original one. My safe arrival was not an entitlement for my extraordinary efforts or skill (I only did my part) but one more example how the confluence of many other factors beyond any of our efforts work together to help us realize a goal.

Being self-satisfied shuts things down. It leads to feeling entitled, since, well, isn’t everything all about me. Gratitude is different; it frees us up, increasing awareness of the wider world, of other and what sustains us minute by minute. Gratitude heals, too.

Years ago, an elderly friend told me of her troubled relationship to her brother. Growing up he treated her contemptuously. As they aged, they rarely communicated. My friend began feeling uneasy: the brother was declining, she was getting older and as difficult as he’d always been, she wanted some kind of healing. She wanted closure in the relationship before they died. How? He was uncommunicative, always distancing.

She came upon this idea. She would write him a letter. She worked hard on it. Writing it surfaced many of the old grievances she had but she didn’t want the letter to be about them, some kind of vindication of past insults.

Instead she listed any experience she could recall for which she felt grateful to him. She documented several, thanking him for those moments he’d offered her. It took some digging around but she found enough instances to warrant writing the letter. As I recall her story she finished the letter but never sent it. She reported how in subsequent meetings she’d felt differently with him as if maybe he’d softened . . . or had she? Who changed? He never saw the letter. What happened?

My friend concluded that she’d changed. That the act of composing the letter, and thinking gratefully, altered how she saw him, and something began shifting deep within her. This created an aura of gentleness in her sufficient to change the climate between them. He did nothing but it appeared he’d been impacted in some imperceptible way, nothing she could point to but whatever it was, it left her feeling that she’d finally made her peace with him. The relationship was not a happy one but the tension was gone whenever they were together. She could now be with him without carrying the baggage of the past which had burdened her.

I regard stories like this holy narratives, where we see the dynamics of real conversion, where all things are made new. As inner growth takes place, gratitude feeds and guides the soul.

Joan Chittister, a Benedictine nun and notable spiritual writer, in her book, “The illuminated Life,” makes the distinction between the superficial changes in our lives, like jobs, houses, relationships and lifestyles and the changes that really count. “Real change,” she writes, “is far deeper [when it] is changing the way we look at life . . . that is the stuff of conversion”

There’s no bigger transformation than going from feeling self-satisfied to being grateful; from harboring grievances to giving thanks; it heals old wounds and leaves us deeply thankful for all the passages we have undertaken in our lives. While not really knowing what we are getting into when we first plan to go from here to there, it’s by grace that we get there safely as often as we do.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.