I’ve not sailed for several years. I miss it.

I’ve arrived at that unhappy confluence where age and agility meet to send a strong message; for my own safety, at this stage in life, I’d be wise to consider other forms of recreation. I began sailing as a boy at fourteen on Raritan Bay and later on Long Island Sound. Today, although I live up a creek, my sailing days are over.

The other day I felt nostalgic about sailing on the Bay. We’d frequently go from home on Broad Creek to the upper reaches of the Tred Avon River for overnights. I remembered one late August morning motoring down the river. It was sunny and cool that day and I was in no hurry to get home. We had anchored up the river and in the morning, it was one of those still and lazy days when I didn’t ever want the trip to end. We were going just south of Oxford and probably doing three knots. I could hear the muffled gurgling of the motor’s discharge as it merged with our wake. It made the boat sound as if it were mumbling about how slow we were moving.

Suddenly just ahead on the starboard bow something broke the water. I couldn’t make anything of it. The surface broke again and then on the port side the same thing happened. Sure enough, dolphins were gamboling downriver with us, finding us agreeable enough to become our traveling companions. For me it was a first. I’d only seen dolphins in pictures. There’s nothing like seeing them surface – as if they were covered all over with mercury making them appear silver and shiny.

They followed us for some distance and finally, near Benoni Point, they submerged one after the other and I didn’t see them again.

Boating on a river is magical. Unlike being surrounded by the expanses of a wide-open Bay, which is a freeing kind of sensation, like watching stars, sailing on rivers is different. The shoreline provides visual boundaries, as the lure of a changing landscape captures our attention always anticipating what’s around the bend. Rivers meander, so that we make it around one bend only to find another waiting for us. The muffled sound of the motor and the hull’s smooth transit as it slides through the still water, sooths the spirit. It’s mesmerizing. Unlike the adrenaline rush I feel on a broad reach in a twenty-knot wind, this is gentler, like gliding.

I remember the sensation from childhood on a day liner going up the Hudson.

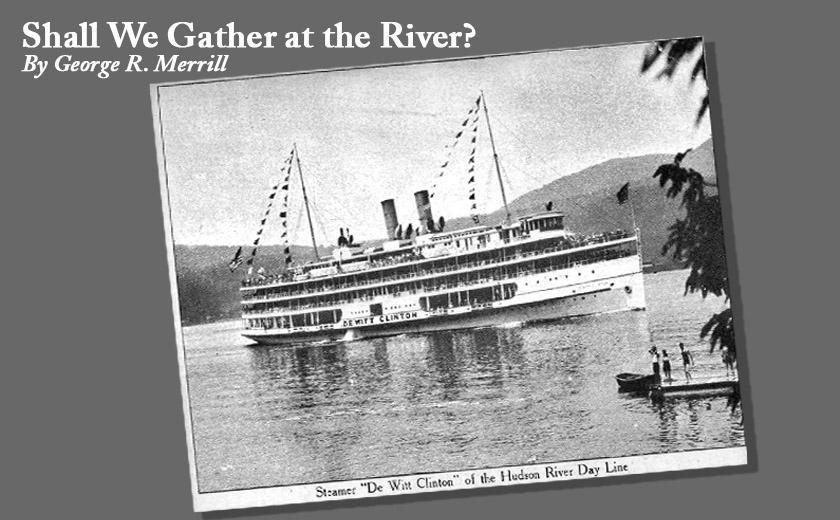

My grandfather skippered the Clermont and the DeWitt Clinton, day liners that left the west side of Manhattan to ply the Hudson River up to Bear Mountain and back. I remember being aboard watching the shoreline steadily rise on both sides as the liner made way north. I don’t remember the water ever being turbulent perhaps because the river was sheltered from wind on both sides by hills and mountains. And too, with the river’s meandering path, the wind couldn’t find a straightaway extensive enough to build up velocity. I remember motion as smooth and calm, the rhythmic thumping of the engines sounding like a heartbeat. Sometimes my grandfather let me stand by the wheelhouse.

I suspect those of us who have motored or sailed the Chesapeake Bay over the years have probably sailed more on its tributaries than on the Bay itself. The Bay has more rivers and streams than our bodies have capillaries.

Rivers characteristically meander. They lend themselves as the perfect metaphor for a spiritual journey. Nobody travels a spiritual journey in a straight line. If it’s going in a straight line you can be sure you’ve gotten off course. In this post-modern era, we have lost the sense of the holy that indigenous people have always felt about rivers and other bodies of water. The Ganges, the Jordon and with our own Columbia River, natives venerated them as sacred. “Shall we Gather at the River” is a beloved protestant hymn celebrating our ultimate reconciliation with God. Moses may have made it to the mountain top, but he was first launched on a river.

The first time I sailed up the Chester River was in late August. We’d sailed from Broad Creek to Corsica Creek to spend the night before going to up to Chestertown. We anchored just off what was then the Russian Embassy’s retreat compound at Pioneer Point, originally the John J. Raskob estate. It was a strange sight to see this lovely mansion, a traditional piece of Americana, with the Soviet Union’s flag, with its hammer and sickle on a red background, flying from a pole on the lawn. It seemed sinister to me. We were being invaded by commies. As we sat in the cockpit having drinks, we’d take binoculars crouch down in the cockpit and furtively spy on the Russians walking around on the property. Odd they didn’t look all that different from Americans.

As a child, my mother read me Kenneth Grahame’s classic, The Wind in the Willows. I’ve remembered parts of it all these years; the charming antics of the characters like Mole, Rat, Badger and Toad. Rat introduces Mole to the river that he lives on. Mole becomes enchanted with it and launches into a paean – lauding the river. Grahame’s description reads like a psalm or even a canticle to the majesty of nature, something worthy of St. Francis of Assisi.

“Suddenly he (Mole) stood by the edge of a full/fed river. Never in his life had he seen a river before – this sleek, sinuous, full bodied animal chasing and chuckling, gripping things with a gurgle, and leaving them with a laugh, to fling itself on fresh playmates that shake themselves free . . . all was a-shake and a-shiver, glints and gleams and sparkles, rustle and swirl, chatter and bubble”

You can feel Grahame’s excitement.

The river is inanimate yet it’s alive; ‘this sleek, sinuous and full-bodied animal’ – it’s beautiful. The river turns this way and that, it takes hold and lets go; it plays, romps and teases playfully like a child. It’s like a sacrament, an outward and visible sign of some inward and spiritual grace, the grace of pure joy. Its properties mediate something divine – is it the beauty of holiness? Grahame sees and hears in the meandering waters of a river, in its inexorable course to the sea, a description of the passages our own lives take.

Speaking of the mystical properties imputed to water; when the Spanish first sailed into the Chesapeake Bay, for its expansiveness and the sense of sanctuary it conveyed, they named it, The Bay of the Mother of God.

Holy Water is not confined to churches. God includes it as a part of nature’s largesse.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.