There is one more thin place I want to revisit with you. It’s not in Mother Africa like Kilimanjaro, nor in Old Europe like the Piazza Navona. It’s here in what some of us mistakenly refer to as the ‘New World,’ but don’t be fooled: this, too, is a very old place, much older, in fact, than the first white men who came to this remote corner of the world seeking refuge and riches, power and position. Like other thin places—places where heaven and earth almost gently touch—it is both suspended in time and very much alive, a place of stillness that nevertheless buzzes with ancient energy. It is both dreamlike and real, a museum-like window into the past but also a place that is still very present in the lives of the 150 people who live there.

In 1992, the United Nations (UNESCO) designated the Taos Pueblo a “World Heritage Site.” By then, the pueblo was already almost a thousand years old. Sited amid the Taos Mountains in the Sangre de Cristo Range in northern New Mexico, it is one of the eight Northern Pueblos inhabited by people who speak variants of the Tanoan language. (There are also ten Southern Pueblo communities in New Mexico, linked to the northern pueblos by culture but not by language.) Perhaps because it is the northernmost and most remote pueblo, Taos is distinct. It is by far the most conservative, private, and secretive of all the Pueblo communities; the rituals and rites of the kivas—the underground ceremonial chambers used by all of the Pueblo People—are rarely, if ever, shared with outsiders.

It has always been this way. A few years ago, I spent several months in the region researching an event known as the Pueblo Revolt. Also known as Popé’s Rebellion, the revolt took place in 1680 and in many ways, it was the first truly American revolution, an uprising of indigenous people against a colonizing power, in this case, the Spanish settlers and missionaries in the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, present day New Mexico. The uprising began in the Taos Pueblo and was guided by Popé (pronounced po-PAY), a mystical holy man who ingeniously planned and orchestrated the revolt which left over 400 Spaniards dead and expelled the remaining 2,000 settlers from the province. Popé promised the people of the pueblos that once the Spanish were gone from the land, their ancient gods would return them to health and prosperity. That mystical belief empowered the revolt and you can still feel its shrouded legacy today.

(Historical footnote: in the rotunda of the US Capitol, each state is entitled to two statues of historical import. For years, there were only 99 statues in the Rotunda; New Mexico had only one. Its second statues was finally added in 2005; it depicts Popé, his back scarred by Spanish lashes and in his left hand, he holds the knotted cord he used as a secret way of timing and initiating the revolt among all the distant peoples of the southern and northern Pueblos.)

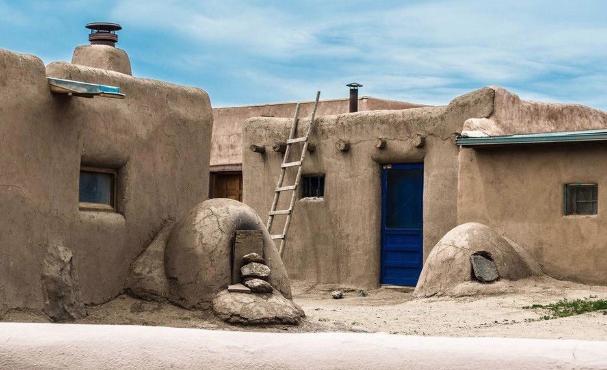

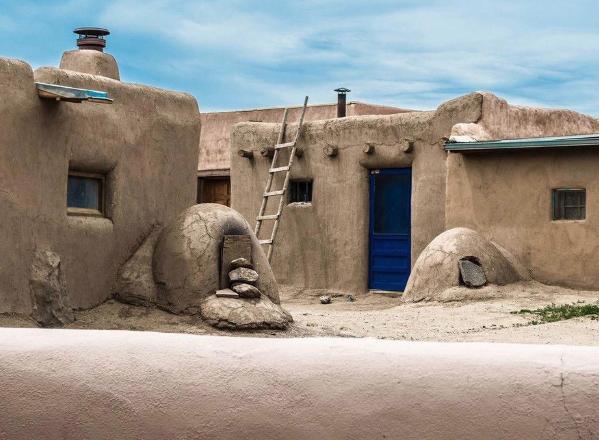

Today, there are two sprawling apartment-like dwellings in Taos Pueblo, North House and South House, as well as a maze of dead-end alleys that wind through the village. Built of adobe and two, sometimes three, stories tall, the great houses face each other across a expansive, open plaza that is bisected by Red Willow Creek, a thin band of water flowing out of the sacred Blue Lake up in the mountains, the ancestral home of the Taos people. On many days, the Pueblo is open to visitors but on Feast Days or, for that matter, on any other day deemed important by its current inhabitants, it is off-limits to the outside world.

I’ve spent many hours in the Pueblo, sitting quietly by the creek, sketching the interplay of light and shadow emanating from the high cumulus clouds that hover over the backdrop of mountains, or just wandering where I am permitted. People are polite but not necessarily welcoming; I understand their wariness. They have been bruised by the world around them but yet they remain willing to share their thin place with us…up to a point, but no further.

According to legend, Taos women used to rub mica into the adobe walls of the Pueblo to make them shine. Some think that maybe it was this trick of light that caused early Spanish explorers to first come to the pueblo in their search for the fabled Seven Cities of Gold. Whatever the reason, that first encounter set in motion a chain of events that are still moving forward today. But, to me, the true power of the Taos Pueblo lies in its natural splendor, its spiritual peace, and the mysterious pulsating energies of heaven and earth that delineate a truly thin place.

I’ll be right back.

Jamie Kirkpatrick is a writer and photographer with homes in Chestertown and Bethesda. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Baltimore Sun, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Washington College Alumni Magazine, and American Cowboy magazine. “A Place to Stand,” a book of photographs and essays about Landon School, was published by the Chester River Press in 2015. A collection of his essays titled “Musing Right Along” was published in May 2017; a second volume of Musings entitled “I’ll Be Right Back” was released in June 2018. Jamie’s website is www.musingjamie.com

Waldemar Kerbel says

We moved from Santa Fe New Mexico after 14 winderduk years in that area. The culture of the Pueblos fascinated us as did the beautiful landscapes.We often relate stories of the Pueblos as other tidbits of interest about New Mexico. It is truly a magical area.