A century and a half after the Civil War and almost fifty years after the Selma to Montgomery Civil Rights Marches, issues of race still chafe at the American soul. With candor and exhilarating compassion, “Raw Nerves: Homage and Provocation,” on view through December 5 at Washington College’s Kohl Gallery, probes into the ongoing process of healing those wounds.

The show presents the work of two African-American artists, Jeffrey Kent of Baltimore and Warren Lyons who lives and works on Staten Island. It’s a stimulating juxtaposition. Kent, the younger of the two, creates mixed media paintings and sculptures full of color, activity and iconic images from the slave era to present. Lyons’s work is far more introspective and meditative. A sampling of six towering portraits from a larger suite begun more than 30 years ago, his paintings are complex studies that look deep into the souls of prominent African- American leaders from Sojourner Truth to John Coltrane.

Kent’s work has the look of protest art but is far more subtle and complex. Strikingly raw and visceral, it abounds with interconnected references to African-American history and sets the stage for an examination of the state of present-day civil rights issues. Much of his concern lies in how quickly the ideals and impetus behind civil rights have faded. It’s a message urging self-reflection that he teasingly underscores by reversing the lettering in some of his paintings so that it only reads clearly when seen in a mirror.

Blackface minstrels and slaves bearing bales of cotton inhabit his bold, cartoonish paintings along with collaged magazine photos of Civil Rights marchers, some of whom wear rose-tinted glasses. His sculptures are made with found objects gathered for their biting significance. In a reference to “whites only” facilities, he sheathed a vintage water fountain in gilt. To procure the cotton actually picked by slaves that appears in several of his works, he hunted down a set of 19th-century chairs upholstered with cotton.

Disturbed by the support given by African-American church groups to California’s ill- fated Proposition 8

Jeffrey Kent, “Can’t Touch This,” 48 x 14.5 x 14.5 inches, 1959 Sunroc water fountain, gold

leaf, Ball Mason jar

banning same-sex marriage, Kent created a series of works in which haloed but blindfolded activists holding Prop 8 placards are shown as blackface buffoons, surrounded by clumps of actual slave-picked cotton. Behind them looms a broad-shouldered black man hefting a bale of cotton, an ancestor whose presence begs the question: who better should know about restricted civil rights than African-Americans?

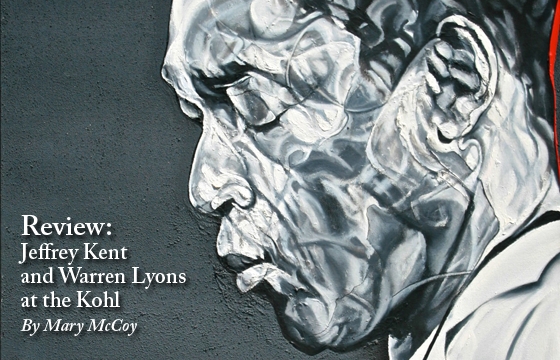

Lyons’s portraits seem quiet and simple by comparison, but this impression evaporates as you look closer. Painting slowly and deliberately in stark black and white, he builds layer upon layer until you can see whole worlds within each face. He may spend several years on a portrait, working from several different photographs and reading biographical materials extensively to learn as much as he can about all aspects of each person’s work and personality. -century chairs upholstered with cotton.

In a sense, he is building on an art historical premise, that of Cezanne and the Cubists who painted objects and scenes from many angles simultaneously. His portrait, “John Coltrane – The Wise One” presents this seminal musician with eyes closed and mouth pursed almost as if he’s playing an introspective tune on an invisible saxophone. His face shimmers and shifts as curving facets reveal pain, patience, compassion, and even what seem to be passages of music itself. Repeating forms at Coltrane’s ear appear like reverberations, while just above his temple are forms that look almost like human figures, one of them perhaps reaching out to beat a drum.

Lyons has lived parallel lives as an artist and a clinical social worker and educator working with troubled families. He likens his painting method to the psychological process of exploring deeper and deeper layers of the human mind. Just as understanding is gained through examination of influences going back not just to childhood, but through multiple generations, his paintings trace the impact of centuries of cultural factors on these prominent African-Americans.

Jeffrey Kent, “From That to This,” 41.5 x 40 inches, acrylic, collage and slave-picked cotton

on canvas

In “Harriet Tubman – Moses,” the fluid lines that define the shadowy contours of her face swirl away above her head into a kind of abstract landscape, perhaps the trails and rivers escaping slaves followed as they journeyed north in search of freedom. The guiding light of their night journeys, the moon, appears above her shoulder, full of unidentifiable textured shapes, like the contours of the unknown future. Hovering in front of her heart is an egg, a universal symbol of potential and new beginnings, while above it is a single drop of red.

This bright red appears as sudden, small details in each of Lyons’s portraits. Singing out against the strongly modeled black and white paint, an arc of red may peek over the curve of a brow or the nape of a neck. Often indicative of danger or anger, in Lyons’s paintings, it reads instead as an enlivening presence shared from one painting to the next, just as human beings share the same red blood regardless of skin color.

Strikingly empathetic and deeply moving, the faces Lyons paints are compressed landscapes of emotion, experience, history and insight. In these people’s eyes, the inner wisdom born of courageous searching for fairness and truth is patently evident. This is precisely the kind of searching that Kent’s work calls for. Despite their different approaches, the work of both artists is clearly focused on the challenge we each face to investigate, rather than repress, our mostly deeply held feelings about race, sexuality and all forms of social division, for only compassionate understanding can heal the wounds afflicting our society.

CARLA MASSONI says

This exhibit is not to be missed. Run – do not walk – to the Kohl Gallery. Jeffrey Kent’s work is a journey through the civil rights movement of the last 50 years. Lyons portraits – a journey to the soul of humanity.