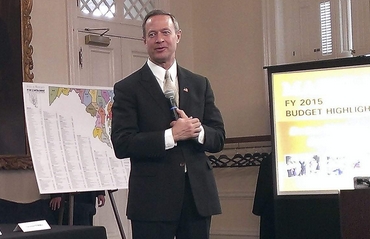

Picking apart Gov. Martin O’Malley’s proposed fiscal 2015 budget, the legislature’s chief fiscal analyst told lawmakers Monday that the administration relied on “familiar budget balancing strategies” to make the numbers work.

According to the fiscal briefing by chief analyst Warren Deschenaux, these tactics in O’Malley’s final spending plan included:

- leaving a fund balance cushion of only $30 million, far too small to cover unexpected spending, known as deficiencies. Deficiencies have averaged $145 million in recent years;

- shifting revenue from dedicated taxes for open space into the general fund pot;

- increasing bond debt to finance the open space programs supposed to be funded by those dedicated taxes;

- giving pay raises in mid year, which requires extra funding in the following budget to pay the full raise;

- providing no money to handle costly court judgments on bail representation and out-of-state taxes;

- tapping into reserves of the employee health benefit fund;

- cutting required pension payments by $100 million.

Concerned about pension cut

Some legislators at the joint hearing of House and Senate budget committees focused on O’Malley’s decision to cut $100 million from a $300 million pension payment mandated when state employees and teachers began contributing more of their salaries to retirement. Unions representing employees and teachers said last week that they were surprised by the cut and the move to make it permanent.

Del. Charles Barkley, D-Montgomery, said, “It seems to me we’re not living up to our part of the bargain.” The legislature promised to use the money from additional employee salary deductions required by a 2011 pension reform to help cure underfunding in the pension system.

“What do we say to our employees?” Barkley asked.

“There’s nothing in the budget that interferes with [pensions] being paid,” Deschenaux said. The true cost is just a one year deferral of 80% funding, from 2024 to 2025.

“By far the largest determining level [of pension funding] is the economy and investment return,” Deschenaux said. “$200 million is roughly the amount the employees were asked to put in” when their pension deductions went from 5% to 7% of salary.

Bond-rating agencies concerned

Barkley also argued that the bond rating agencies “were not real happy with what we were doing.” But Deschenaux disagreed, saying he participated in the conference calls with the rating agencies, and they did not raise that issue.

The three New York bond-rating agencies have praised Maryland’s pension reforms of 2011, but in most reports done before bond sales, they raise concerns about Maryland’s high pension liabilities.

Maryland has $40 billion in its pension fund, plenty to cover paying current retirees but only 65% of what’s needed to pay all future pension promises.

Del. Gail Bates, R-Howard, an accountant who has frequently introduced legislation to change Maryland’s pension system and its accounting, asked if the plan would reduce payments to the pension fund by $1 billion.

Deschenaux pointed to a chart in the briefing book (page 29) that shows the $100 million cut $600 million over 12 years, as other pension contributions must be increased to make up for lost investment earnings.

Unions will be lobbying to remove the permanent cut in pension funding, according a statement from the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees.

“AFSCME is reaching out the legislators now to eliminate the language which permanently reduces the investment into the pension fund and replace it with language which forbids it in the future.”

By Len Lazarick

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.